Thanks to @KateSwaffer.

The time is now right to promote specialist nurses in ‘dementia friendly communities’

There was a time when the GP used to be at the heart of a person’s community, as well as ‘delivering care’. For some people, there is no such thing as society, and the community consists of high street brands, banks and services (such as police or fire).

I’ve spent some time thinking about the implementation of the ‘dementia friendly community’ policy in a number of jurisdictions. It really has struck me how, for whatever political reasons, nurses are not perceived to be the heart of dementia friendly communities in England.

This, I feel, is a great tragedy. I don’t deny there are about a hundred different causes of a dementia, people’s social circumstances will differ (it is not uncommon for a female widower to develop a dementia while very lonely), cultural differences exist (for example in the rôle of the family in those of an Asian background), there are different rates of progression, and so on.

On receiving a diagnosis, I think support services in dementia should be much stronger than now. What is all too commonplace is a travesty. People don’t know where to turn to for basic information about clinical aspects, or wider aspects about living in the community.

As the dementia progresses, in the later stages, a focus will be to keep the person out of hospital wherever possible. Clearly, support and care in the community need to be funded properly.

A ‘crisis’ for a person living with dementia is where a ‘stressor’ causes that person no longer to be able to cope with living in his or her usual environment. There could be a number of causes of that, but it’s noteworthy that many of them are in fact medical. I disagree a specialist nurse in dementia is necessarily a job for a community psychiatry nurse (“CPN”), as the workload of such nurses tends to be very big.

But seeing a rôle for a CPN is not a trivial one, as I’m a fully signed up devotee of ‘parity of esteem’ where mental health is not seen as the ugly sister of physical health. For that matter, social work practitioners, who often find themselves at the heart of mental capacity decisions and safeguarding issues, should be on an equal footing too with other professionals.

I said to Chris, a friend of mine living well with dementia recently, “GPs will even be in a good position to coordinate information”.

I was in fact repeating words from a GP.

Chris, “So why don’t they?”

In certain respects, in designing a system you wouldn’t wish to start from here.

Without the focus on ‘budgets’ which do not necessarily deliver the ‘right kind’ of choice for the person with the health and care matters, it’s important that people with dementia have rights to a personal care plan, which is responsive to that person’s needs in real time. Knowing someone’s background is particularly essential in people with Alzheimer’s disease where longer term memories may be more intact. Knowing someone as a person is of course at the heart of personhood, through maybe a ‘life story’.

I don’t think it should be a ‘luxury’ of people with dementia following them after diagnosis through the system. I think, in fact, it should be an essential aspiration. It’s really important that somebody can cross off inappropriate medications, such as perhaps antipsychotics, on a drug chart if the person with dementia might not benefit.

It might help if a dementia specialist companion could spot problems in overmedicated people for blood pressure, for example. These individuals might become at risk of falls (and subsequent bone fractures if living with osteoporosis). Or somebody may be developing constipation or a stinging urine, becoming acutely confused. Dementia is not simply caused by conditions of old age, but frail individuals can do particularly bad when coming into contact with hospitals.

In the scenario that a person with dementia at any stage does need to go into hospital, it would help enormously if there could be continuity of care between the community and hospital. People with all types of dementia can find unfamiliarity, in people and environments, extremely mentally distressing, and this can be detrimental to their physical health (taking a whole person care approach). There are few people better than paid carers, with pay above the national minimum wage, and not on zero hour contracts, and unpaid caregivers including friends and family, to inform on these care plans, but the person living with dementia is the one for whom the plan is being designed.

All staff clearly need to be informed and skilled about dementia, and it is vital that resources are put aside for the adequate training of the workforce. The workforce themselves want this.

It won’t be a surprise to you to learn that I see specialist nurses in prime position to offer a huge deal to the implementation of whole person care for dementia from the next Government?

I think my views are broadly consistent with a number of places. A number of reports across jurisdictions have been important in establishing the direction of travel for acute hospital care: e.g. “Dementia care in the acute hospital setting: issues and strategies: a report for Alzheimer’s Australia” (Alzheimer’s Australia, June 2014), “Spotlight on dementia care: a Health Foundation Improvement Report” (Health Foundation, October 2011), and the Royal College of Nursing’s report “Commitment to the care of people with dementia in hospital settings” (RCN, January 2013).

Examples of appropriate clinical leads, as the RCN themselves recognise, are “Admiral nurses” from the charity @DementiaUK, Alzheimer Scotland dementia specialist nurses, dementia champions in Scotland, and ward champions. Merely having ‘dementia advisors’ will be a case of the bland and ill informed leading the bland, on the other hand.

Like many other ‘once in a lifetime opportunities’, if we get this right the service could be vastly improved. I am confident that, if given the proper funding to make this happen, and strong leadership cascades downwards, the next Government will rise to this challenge.

Trivialising dementia – too much inappropriate rocking of the boat?

When I wrote my highly successful book, “Living well with dementia”, using the phrase deliberately from the 2009 English dementia strategy document for England, I never knew the phrase was being bastardised so much for often very trivial initiatives in dementia.

On the other hand, I had huge delight in seeing its immediate relevance to a carers’ support group I went to last week.

I feel deeply hurt that the serious issues in my book, such as advocacy for mental capacity, the presentation of the cognitive neurology of the dementias, or the use of ambient-assisted technology have not been widely discussed amongst the wider community.

In that, I feel the book has failed.

I welcome proposals for the next Government to maximise money into actual service, and to re-establish health funding in line with other comparator countries.

Commissioning in dementia is now not based on what is best for the person for the person with dementia, but what is best for your Twitter commissioner friends.

I look forward to the Health and Wellbeing Boards playing a pivotal rôle in establishing some sort of normality for what commissioning in living well with dementia might be as a value-based outcome.

The strangehold of “shiny”, “off the shelf” “innovative packages”, in the drive for the current Government to ‘liberalise’ the financial market in dementia has acted for a cover for disturbing, unacceptable cuts in dementia service provision in the last few years.

I remember ‘boat rocking’ the first time around from the elegant work of Prof Debra Meyerson.

I do not wish to promote frontline professionals, many of whom have spent seven years at least at medical school or in their nursing training, to become lambs to the slaughter in the modern NHS and social care.

Keeping it real, we know that real frontline professionals in medicine and social care, even if they are not in a downright toxic environment requiring whistleblowing, can find it dangerous being risk appetitive.

Indeed, being risk appetitive, while great for innovation and leadership, can literally be deadly for patient safety.

The next Government has enough on its hands with enforcing care home standards and sanctioning for offences against the national minimum wage for paid carers as it is.

We have to think for a second for the vast army of paid workers in the NHS, as well as the rather well paid people who like their shiny new boxes, I feel.

The schism between the social media and what is happening at service level I think is most alarming, and perhaps symptomatic about how the health and social care services have begun to work in reality.

All too often, I am having first hand experience of busy frontline nurses being dragged in front of entrepreneurs in their local dementia economy to hear shills beginning, “I don’t have first hand experience of caring in dementia, but…”, before the hard sell.

This is tragically being reflected on the world stage too, though I do anticipate that the G7 legacy event from Japan which is looking carefully at their experience with care and support post diagnosis, next year, will be brilliant.

It is important for leaders in dementia to have authenticity.

I have severe doubts and misgivings about what gives the World Dementia Envoy the appropriate background and training in dementia for him to be in this important post.

It is all too easy for ‘thought leaders’ in corporate-like medical charities to have no formal qualifications or training in medicine, nursing, or social care, and opine nonetheless about weighty issues to do with policy.

I am concerned that the global ‘dementia friendly communities’ policy plank appears to have been straightjacketed through one charity in England, when it is patently obvious that various other charities such as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation have made a powerful contribution.

The media have largely not engaged in a discussion about living well with dementia, but engaged simply with Dementia Friends or a story arising out of that.

I am alarmed about the lack of plurality in the dementia research sector.

I think the All Party Parliamentary Group (“APPG”) for dementia have done some valuable work, but their lack of momentum on specialist nurses including Admiral nurses, spearheaded by the charity Dementia UK, seriously offends me.

I am sick of how the notion of ‘involvement’ of people with dementia has been abused in service provision mostly, although I am encouraged very much by initiatives such as from DEEP and Innovations in Dementia.

I think there have been genuine improvements in engaging people with dementia in research, through a body of work faithfully peer-reviewed in the Dementia Journal looking at heavy issues such as the meaning of real consent.

I am now going to draw the line of tokenistic involvement of people with dementia to front projects without any meaningful inclusion.

And in fairness, this tokenistic involvement is, I am aware, happening in various jurisdictions, not just England.

All too often, “co-production” has become code for ‘exploitation’ rather than ‘active partnership’.

The prevalence of dementia is actually falling in England, it is now thought.

The ‘dementia challenge’ was our challenge to making sure that we adequately safeguarded against people rent seeking from dementia since 2012.

In that, I think we have spectacularly failed.

I am overall very encouraged, however, with the success of the huge amount of work which has been done, including from the highly influential Alzheimer’s Society, and from the communitarian activism of “The Purple Angels”.

All this ‘radicalism’ has taken on a rather ugly, conformist twang.

Now is though time to ‘take stock’, as Baroness Sally Greengross, the current chair of the APPG on dementia, herself advised, as the new England dementia strategy is being drafted ahead of the completion of the current one in March 2015.

Meeting the needs of persons with younger onset dementia and their supporters

There are many different types of dementia. I happen to believe it’s possible to live well with dementia.

That’s why I wished to travel to Robertsbridge from London Charing Cross to see Charmaine and family, and to give her a copy of my book which I had promised her.

“Living well with dementia” is also the name of the current (five year) dementia strategic framework for England, which is about to be renewed.

The ‘behavioural variant’ of frontotemporal dementia is normally a dementia which occurs in younger people (below the age of 65), with quite a subtle progressive change in behaviour and personality noticed by others.

Early on, in this condition, problems in short term memory and new learning are not in fact common, leading many persons with this dementia to score very highly on the MMSE screening test.

Meanwhile, the ‘temporal variant’ of frontotemporal dementia encompasses several different subtypes.

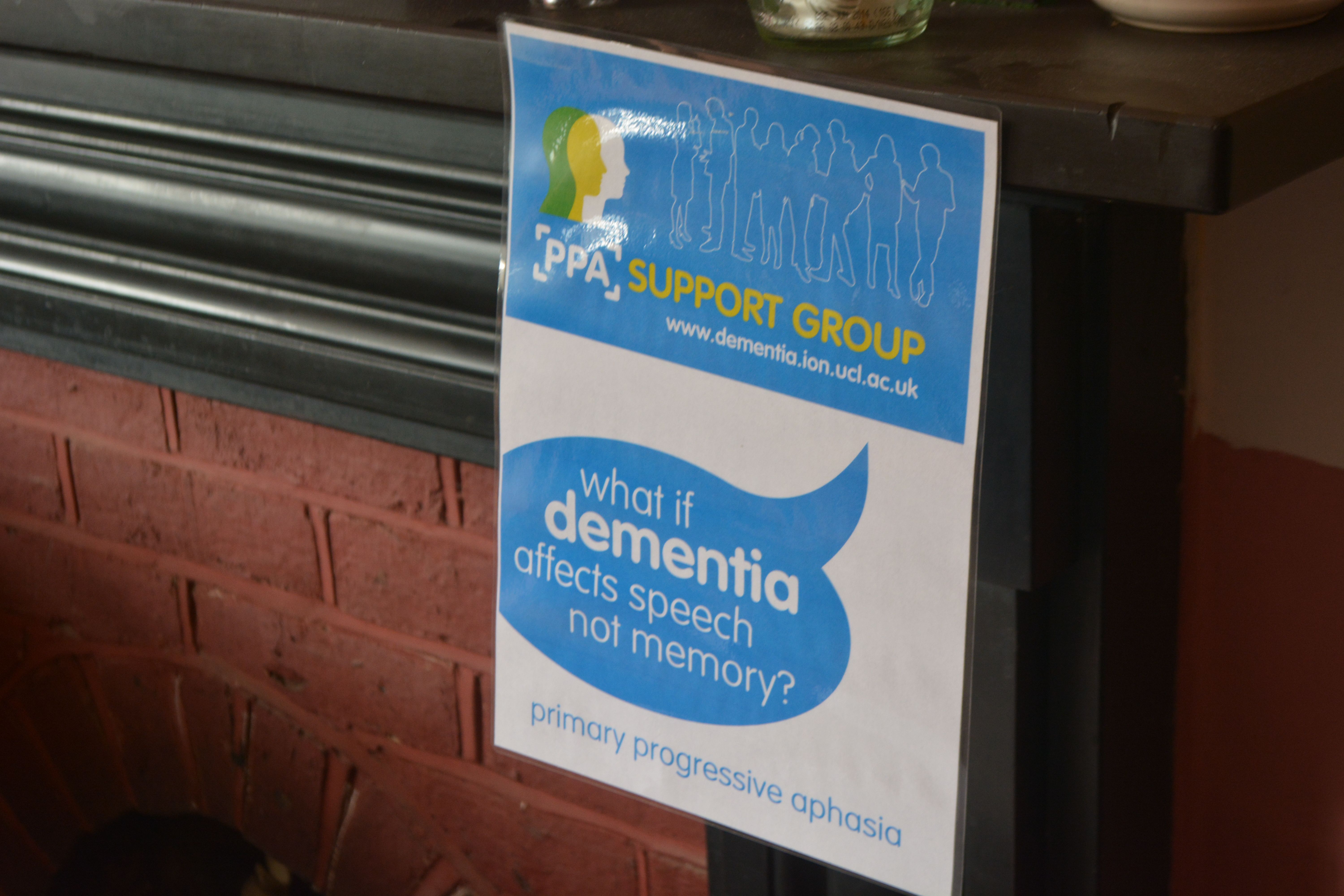

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA), one of these subtypes, is a language disorder that involves changes in the ability to speak, read, write and understand what others are saying. It is usually acknowledged to be properly described by Mesulam.

Problems with memory, reasoning, and judgment are not thought to be usually apparent at first, but can develop over time.

It is associated with a disease process that causes atrophy in the frontal and temporal areas of the brain, and is distinct from aphasia resulting from a stroke.

In 2011, criteria were adopted for the classification of PPA into three clinical subtypes: nonfluent/agrammatic variant PPA, semantic variant PPA and logopenic variant/phonological PPA.

Therefore the frontotemporal dementias are not usually, early on, characterised by problems in memory for events and facts.

PPA can, as it progresses, be accompanied with anxious behaviours manifest as obsessive-compulsions.

The ‘Dementia Research Centre’ (part of University College London, to which the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery and Institute of Neurology are associated or attached) hosts a number of superb support groups.

The PPA Support Group holds a number of support groups at regular time intervals. Their newsletter from August 2014 is here.

The convener is Jill Walton, at jill.walton@ftdsg.org.

I attended yesterday’s meeting.

My close #Twitter pal Charmaine, @charbhardy (Charmaine Hardy), invited me down to Robertsbridge, East Sussex, for Wednesday September 17 2014 from 12 noon to 2pm.

Charmaine describes herself as “I’m a carer to a husband with PPA dementia.”

Of course, Charmaine, her husband and me were in attendance as part of this impressive group of twelve delegates.

Charmaine also claims “Love my garden I post too many pics.” I disagree though on the latter half – Charmaine never posts too many pics of her garden. Here is a photograph I took of a very beautiful flower of hers.

This is in fact the pergola Charmaine’s husband built with Paul.

The meeting was held in one of the venue rooms at The Ostrich Hotel (“The Ostrich”), Station Road, Robertsbridge, East Sussex, T 32 5DJ.

The Ostrich is an outstanding B&B housed in a gorgeous Victorian location, with a spectacular tropical garden.

I had the pleasure of sampling a delicious supper with Charmaine and her husband.

Our couple of hours yesterday was an informal meeting for people affected by a diagnosis of PPA, their family and friends. We all thought the meeting was fantastic.

Jill showed a video for teaching purposes of what the language presentations of dementia, including PPA, are broadly like.

We all participated in an activity where we had to express the meaning of a sentence without using any of the words, e.g. “Part of my leg is hot and painful.” It was difficult!

The meeting was very enjoyable, but we were able to discuss many issues.

We discussed how the diagnosis of dementia could mean a contraction of your friends’ network, leading to loneliness.

We also discussed how greater education of what the dementias are would help to overcome stigma and discrimination against people living with dementia.

Overall, the feeling of the group was each person living with dementia must be treated with dignity as an unique individual with a significant past and present.

We also felt that the ‘one glove fits all’ approach of housing and accommodation doesn’t work, and forcing people with dementia into accommodation solutions they’re not happy with is bound to cause distress.

This can be a particular problem with younger patients with dementia, who wish to lead independent lives as long as possible, not wishing to be forced into an old people’s home.

If a younger person who receives a diagnosis of dementia it can be challenging to deal with your employer; the construct of ‘dementia friendly communities’, which is said to promote inclusivity, cannot adequately protect against unlawful discrimination if people are not aware of their legal rights and have inadequate access to justice.

PPA also has particular resonance in English policy as a noteworthy example of a younger onset dementia. A ‘younger onset dementia’ refers to a dementia which occurs before 65.

This cut-off is completely arbitrary, however (as arbitrary as the “retirement age”).

Younger onset dementia is a distinct group of people living with dementia, because the conditions which cause these dementias tend to be late presentations of “young” conditions or early presentations of “old” conditions.

In theory, the ‘younger onset dementia’ label is inaccurate, in that a dementia might start long before the symptomatic presentation of people with dementia. At one extreme, some people with the very rare genetic presentations of dementia are born with their dementias (or indeed have the genetic make-up in utero.)

It is therefore clear that we need a much greater sophistication in responding to the needs, beliefs, concerns and expectations of people with younger onset dementia.

The unique identity of people with younger onset dementia means that they have distinct research and service provision needs.

This is particularly true as some of the younger onset dementia can be accompanied by obvious movement and psychiatric symptoms, such as forms of prion disease (GSS and CJD) or Huntington’s disease.

A longstanding problem with the organisation of services is that mental illness problems have traditionally played ‘second fiddle’ to medical problems.

This is exacerbated by the drastic cuts in social care which have relentlessly continued in the last few years.

It is hoped that some of these problems in ‘parity of esteem’ might be mitigated against through ‘whole person care’, the expected policy from May 8th 2015 to integrate health and social care properly for the first time.

I had a very nice conversation with Fiona Chaâbane from the University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust.

Fiona’s rôle there is as a clinical nurse specialist in dementia, and as a clinical coordinator for Huntington’s disease and younger onset dementia.

I am hopeful that the ‘care coordinator’ rôle will be properly fleshed out in the next government, which will see a more substantial rôle for specialist and general nurses within networks comprising ‘dementia friendly communities’.

I feel that, in many of these conditions, cognitive or psychiatric features can be prominent early on.

My concern about the misdiagnosis of these dementias which do not have a strong component of a failure of memory is a very substantial one.

A misdiagnosis (e.g. of a dementia -> non-dementia such as anxiety or depression) can not only mean that person not obtaining the proper medical treatment, but can also mean that that person goes down a clinical pathway for which he or she is not appropriate. This can also impact on that person’s life and job in an utterly destructive way, particularly more so if before retirement age.

Thanks to Jill, Charmaine, her husband and the PPA support group for educating me properly about the dementias. It was particularly helpful to me too in confirming my concerns about research and service provision for the younger onset dementias in England, unfortunately. But at least we can now all begin to address them.

The references for chapter 1 of my book on prevention/risk factors in dementia

These are the references to Chapter 1 “Introduction”, mainly an overview of English dementia policy, prevention and risk factors, for my new book, “Living better with dementia: championing change for the future” (to be published early 2014).

Websites

“Call to action: the use of antipsychotics for people with dementia” http://www.institute.nhs.uk/qipp/calls_to_action/Dementia_and_antipsychotic_drugs.html

A letter to the Prime Minister charting progress on the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge (dated 7th May 2014). https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/media.dh.gov.uk/network/353/files/2014/05/10092-2902335-TSO-Dementia-Letter-to-PM-ACCESSIBLE.pdf

All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on dementia. (2012) Unlocking the diagnosis: the key to improving the lives of people with dementia http://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?fileID=1457 (dated June)

Dementia 2013: The hidden voice of lonelineness http://www.alzheimers.org.uk/dementia2013

Dementia Roadmap. http://dementiaroadmap.info

Department of Health (2012) Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge: delivering major improvements in dementia care and research by 2015 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215101/dh_133176.pdf

Making a Difference in Dementia: Nursing Vision and Strategy https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/147956/Making_a_Difference_in_Dementia_Nursing_Vision_and_Strategy.pdf

Memory Services National Accreditation Programme (Royal College of Psychiatrists) http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/workinpsychiatry/qualityimprovement/qualityandaccreditation/memoryservices/memoryservicesaccreditation.aspx

NHS Confederation website/NHS Voices blog. (2014) A people-centred response to the 2015 Challenge is vital for the future of health and care, says Jeremy Taylor, http://www.nhsconfed.org/blog/2014/06/a-people-centred-response-to-the-2015-challenge-is-vital-for-the-future-of-health-and-care

PM Challenge on dementia (Alzheimer’s Research UK) http://www.alzheimersresearchuk.org/news-detail/10688/PM-Challenge-on-Dementia-a-year-of-progress-and-new-promise-for-research/ (dated 15 May 2013)

Public Health England and UK Health Prevention First (2014). The Blackfriars Consensus on promoting brain health: reducing risks for dementia in the population http://nhfshare.heartforum.org.uk/RMAssets/Reports/Blackfriars%20consensus%20%20_V18.pdf (“Blackfriars Consensus Statement”)

Rahman, S. (2014) “It’s time we talked about ‘dementia friendly communities’” Living well with dementia blog, http://livingwelldementia.org/2014/03/25/its-time-we-talked-about-dementia-friendly-communities/ (25th March 2014).

Report on the prescribing of anti-psychotic drugs to people with dementia (author: Professor Banerjee) http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http:/www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_108303 (November 2009)

WHO (2013) [ed. Wilkinson, R., Marmot, M.] Social determinants of health: the solid facts. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/98438/e81384.pdf

Other references

Ahlskog, J.E., Geda, Y.E., Graff-Radford, N.R., Petersen, R.C. (2011) Physical exercise as a preventive or disease-modifying treatment of dementia and brain aging, Mayo Clin Proc, 86(9), pp. 876–84.

Albert, M.S., DeKosky, S.T., Dickson, D., Dubois, B., Feldman, H.H., Fox, N.C,., Gamst, A., Holtzman, D.M., Jagust, W.J., Petersen, R.C., Snyder, P.J., Carrillo, M.C., Thies, B., Phelps, C.H. (2011) The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due toAlzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease, Alzheimers Dement, 7, pp. 270–9.

Alzheimer’s Association Expert Advisory Workgroup on NAPA (2012) Workgroup on NAPA’s scientific agenda for a national initiative on Alzheimer’s disease, Alzheimer Dement, 8, pp. 357–361.

Bambra, C., Gibson, M., Sowden, A., Wright, K., Whitehead, M., Petticrew, M. (2010) Tackling the wider social determinants of health and health inequalities: evidence from systematic reviews, J Epidemiol Community Health, Apr, 64(4), pp. 284-91.

Barberger-Gateau, P., Raffaitin, C., Letenneur, L., Berr, C., Tzourio, C., Dartigues, J.F., Alpérovitch, A. (2007) Dietary patterns and risk of dementia: the Three-City cohort study. Neurology, Nov 13, 69(20), pp. 1921-30.

Bennett, D.A., Schneider, J.A., Tang, Y., Arnold, S.E., Wilson, R.S. (2006) The effect of social networks on the relation between Alzheimer’s disease pathology and level of cognitive function in old people: a longitudinal cohort study, Lancet Neurol, 5(5), pp. 406–12.

Beydoun, M.A., Beydoun, H.A., Wang, Y. (2008) Obesity and central obesity as risk factors for incident dementia and its subtypes: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Obes Rev, 9, pp. 204–218.

Biessels GJ. Capitalising on modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol, Aug, 13(8), pp. 752-3.

Black, S.E., Patterson, C. Feightner, J. (2001) Preventing dementia, Canadian Journal of Neurology Science, 28 (Suppl 1), pp. S56–66.

Blackburn, D.J., Krishnan, K., Fox, L., Ballard, C., Burns, A., Ford, G.A., Mant, J., Passmore, P., Pocock, S., Reckless, J., Sprigg, N., Stewart, R., Wardlaw, J., Bath, P.M. (2013) Prevention of Decline in Cognition after Stroke Trial (PODCAST): a study protocol for a factorial randomised controlled trial of intensive versus guideline lowering of blood pressure and lipids, Trials, Nov 22, 14: 401.

Bond, J. (1992) The medicalization of dementia, Journal of Aging Studies, 6, 397–403.

Bowling, A. (2007) Aspirations for old age in the 21st century, what is successful aging? The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 64, 263–297.

Boyle, P.A., Buchman, A.S., Wilson, R.S., Yu, L., Schneider, J.A., Bennett, D.A. (2012) Effect of purpose in life on the relation between Alzheimer disease pathologic changes on cognitive function in advanced age, Arch Gen Psychiatry, 69(5), pp. 499– 505.

Brodaty, H., Howarth, G., Mant, A., Kurle, S. (1994) General practice and dementia, A national survey of Australian GPs, Medical Journal of Australia, 160, 10–14.

Brooker, D., La Fontaine, J., Bray, J., Evans, S. (for the University of Worcester Association of Dementia Studies) (2013), Timely diagnosis of dementia: ALCOVE WP5 Task 1 and 2.

Brunet M. (2014) Targets for dementia diagnoses will lead to over-diagnosis, BMJ, 348:g2224.

Brunnström, H., Gustafson, L., Passant, U., Englund, E. (2009) Prevalence of dementia subtypes: a 30-year retrospective survey of neuropathological reports, Arch Gerontol Geriatr, Jul Aug, 49(1), pp. 146-9.

Buchman, A.S., Wilson, R.S., Bienias, J.L., Shah, R.C., Evans, D.A., Bennett, D.A. (2005) Change in body mass index and risk of incident Alzheimer disease, Neurology, 65, pp. 892–897.

Burns, A., Robert, P. (2009) The National Dementia strategy in England, BMJ, Mar 10, 338:b931.

Chang, M., Jonsson, P.V., Snaedal, J., Bjornsson, S., Saczynski, J.S., Aspelund, T., Eiriksdottir, G., Jonsdottir, M.K., Lopez, O.L., Harris, T.B., Gudnason, V., Launer, L.J. (2010) The effect of midlife physical activity on cognitive function among older adults: AGES—Reykjavik study, J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 65(12), pp. 1369–74.

Cooper, C. (2013) G8 Dementia Summit: PM pledges to double funding for research by 2025, 11 December 2013, The Independent newspaper, http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/health-news/g8-dementia-summit-pm-pledges-to-double-funding-for-research-by-2025-8996377.html

Crampton, J., Dean, J., Eley, R. (2012) Joseph Rowntree Foundation: Creating a dementia friendly York, http://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/files/jrf/dementia-communities-york-full.pdf.

Cunningham, E.L., Passmore, A.P. (2013) Drug development in dementia, Maturitas, 76(3), pp. 260-6.

Daviglus, M.L., Bell, C.C., Berrettini, W., Bowen, P.E., Connolly, E.S. Jr, Cox, N.J., Dunbar-Jacob, J.M., Granieri, E.C., Hunt, G., McGarry, K., Patel, D., Potosky, A.L., Sanders-Bush, E., Silberberg, D., Trevisan, M. (2010) National institutes of health state-of-the-science conference statement: preventing Alzheimer disease and cognitive decline, Annals of Internal Medicine, August 3, 153(3), pp. 176–81.

De Lepeliere, J., Wind, A., Iliffe, S., Moniz-Cook, E., Wilcock, J., Gonzalez, V., Derksen, E., Gianelli, M., Vernooij-Dassen, M. the Interdem Group. (2008). The primary care diagnosis of dementia in Europe: An analysis using multi-disciplinary, multi-national expert groups, Aging & Mental Health, 12(5), 568–576.

Desmond, D.W., Tatemichi, T.K., Paik, M., Stern, Y. (1993) Risk factors for cerebrovascular disease as correlates of cognitive function in a stroke free cohort, Archives of Neurology, 50, pp. 162–166.

Devi, G., Ottman, R., Tang, M., Marder, K., Stern, Y., Tycko, B., Mayeux, R. (1999) Influence of APOE genotype on familial aggregation of AD in an urban population, Neurology, 53: 789.

Devore, E.E., Grodstein, F., van Rooij, F.J., Hofman, A., Stampfer, M.J., Witteman, J.C., Breteler M.M. (2010) Dietary antioxidants and long-term risk of dementia, Arch Neurol, Jul, 67(7), pp. 819-25.

Downs, M., Turner, S., Iliffe, S., Bryans, M., Wilcock, J., Keady, J. (2003) Improving the response of primary care practitioners to people with dementia and their families: A randomised controlled trial of educational interventions. Final Report to the UK Alzheimer’s Society, Bradford: UK Alzheimer’s Society.

EClipSE Collaborative Members, Brayne, C., Ince, P.G., Keage, H.A., McKeith, I.G., Matthews, F.E., Polvikoski, T., Sulkava, R. (2010) Education, the brain and dementia: neuroprotection or compensation? Brain, Aug, 133(Pt 8), pp. 2210-6.

Gao, S., Hendrie, H. C., Hall, K. S, Hui, S. (1998) The relationships between age, sex, and the incidence of dementia and Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis, Archives of General Psychiatry, 55, 809–815.

Gauthier, S., Leuzy, A., Racine, E., Rosa-Neto, P. (2013) Diagnosis and management of Alzheimer’s disease: past, present and future ethical issues, Prog Neurobiol, Nov. 110:102-13.

Gustafson, D.R., Backman, K., Waern, M., Ostling, S., Guo, X., Zandi, P., Mielke, M.M., Bengtsson, C., Skoog, I. (2009) Adiposity indicators and dementia over 32 years in Sweden. Neurology, 73, pp. 1559–1566.

Haase, H., Rink, L. (2009) Functional significance of zinc-related signaling pathways in immune cells, Annu Rev Nutr, 29, pp. 133–152.

Håkansson, K., Rovio, S., Helkala, E.L., Vilska, A.R., Winblad, B., Soininen, H., Nissinen, A., Mohammed, A.H., Kivipelto, M., .Soininen H., Nissinen, A., Mohammed, A.H., Kivipelto, M. Association between mid-life marital status and cognitive function in later life: population based cohort study, BMJ, 339:b2462.

Hansen, E.C., Hughes, C., Routley, G., Robinson, A.L. (2008) General practitioners’ experiences and understandings of diagnosing dementia: factors impacting on early diagnosis, Soc Sci Med, Dec, 67(11), pp. 1776-83.

Harvey, R.J., Rossor, M.N., Skelton-Robinson, M. (1998) Young onset dementia: epidemiology, clinical symptoms, family burden, support and outcome, London: Dementia Research Group.

Hofman, A., Ott, A., Breteler, M.M., Bots, M.L., Slooter, A.J., van Harskamp, F, van Duijn, C.N., Van Broeckhoven, C., Grobbee, D.E. (1997) Atherosclerosis, apolipoprotein E, and prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in the Rotterdam Study, Lancet, 349, pp. 151–154

Holland, W. (2012) Competition or collaboration? A comparison of health services in the UK, Clinical Medicine, 10(5), pp. 431–3

Imtiaz, B., Tolppanen, A.M., Kivipelto, M., Soininen. H. (2014) Future directions in Alzheimer’s disease from risk factors to prevention, Biochem Pharmacol, Apr 15, 88(4), pp. 661-70.

Innes, A., Manthorpe, J. (2013) Developing theoretical understandings of dementia and their application to dementia care policy in the UK, Dementia (London), Nov, 12(6), pp. 682-96.

Ionicioiu, I., David, D., Szamosközi, S. (2014) A quantitative meta-analysis of the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in dementia, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 27, pp. 591 – 594.

Jenkins, C.R., Thien, F.C.K., Wheatley, J.R., Reddel, H.K. (2005) Traditional and patient-centred outcomes with three classes of asthma medication, European Respiratory Journal, 26(1), pp. 36-44.

Jiang, T., Yu, J.T., Tian, Y., Tan, L. (2013) Epidemiology and etiology of Alzheimer’s disease: from genetic to non-genetic factors, Curr Alzheimer Res, Oct, 10(8), pp. 852-67.

Johansson, L., Guo, X., Waern, M., Ostling, S., Gustafson, D., Bengtsson, C., Skoog, I. (2010) Midlife psychological stress and risk of dementia: a 35-year longitudinal population study. Brain, Aug, 133(Pt 8), pp. 2217-24.

Jorm, A.F., Jolley, D. (1998) The incidence of dementia: a meta-analysis, Neurology, 51, 728–33.

Kehne, J.H. (2007) The CRF1 receptor, a novel target for the treatment of depression, anxiety, and stress-related disorders, CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets, 6, pp. 163–182.

Khachaturian, A.S., Meranus, D.H., Kukull, W.A., Khachaturian, Z.S. (2013) Big data, aging, and dementia: pathways for international harmonization on data sharing, Alzheimers Dement, 9 (5 Suppl), pp. S61-2.

Khachaturian, Z.S., Petersen, R.C., Snyder, P.J., Khachaturian, A.S., Aisen, P., de Leon, M., Greenberg, B.D., Kukull, W., Maruff, P., Sperling, R.A., Stern, Y., Touchon, J., Vellas, B., Andrieu, S., Weiner, M.W., Carrillo, M.C., Bain, LJ. (2011) Developing a global strategy to prevent Alzheimer’s disease: Leon Thal Symposium 2010, Alzheimers Dement, Mar, 7(2), pp. 127-32.

Kim, J.W., Lee, D.Y., Lee, B.C., Jung, M.H., Kim, H., Choi, Y.S., Choi, I.G. (2012) Alcohol and cognition in the elderly: a review, Psychiatry Investig, Mar, 9(1), pp. 8-16.

Kivipelto, M., Ngandu, T., Fratiglioni, L., Viitanen, M., Kareholt, I., Winblad, B., Helkala, E.L., Tuomilehto, J., Soininen, H., Nissinen, A. (2006) Obesity and vascular risk factors at midlife and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease, Arch Neurol, 62, pp. 1556–1560.

Kmietowicz, Z. (2012) Cameron launches challenge to end “national crisis” of poor dementia care, BMJ, 344, e2347.

Kmietowicz, Z. (2014) Recorded diagnosis of dementia in England increases by 62% since 2006, BMJ, 349, g4911.

Koch, T., Iliffe, S. (2011) Implementing the National Dementia Strategy in England: Evaluating innovative practices using a case study methodology, Dementia, 10(4) 487–498.

Kopelman, P.G., (2000) Obesity as a medical problem, Nature, 404, pp. 635–643.

Lautenschlager, N.T., Cupples, L.A., Rao, V.S., Auerbach, S.A., Becker, R., Burke, J., Chui, H., Duara, R., Foley, E.J., Glatt, S.L., Green, R.C., Jones, R., Karlinsky, H., Kukull, W.A., Kurz, A., Larson, E.B., Martelli, K., Sadovnick, A.D., Volicer, L., Waring, S.C., Growdon, J.H., Farrer, L.A. (1996) Risk of dementia among relatives of Alzheimer’s disease patients in the MIRAGE study: What is in store for the oldest old? Neurology, 46, pp. 641–50.

Leonard BE. (2006) HPA and immune axes in stress: involvement of the serotonergic system. Neuroimmunomodulation, 13, pp. 268–76.

Lieb, W., Beiser, A.S., Vasan, R.S., Tan, Z.S., Au, R., Harris, T.B., Roubenoff, R., Auerbach, S., De- Carli, C., Wolf, P.A., Seshadri, S. (2009) Association of plasma leptin levels with incident Alzheimer disease and MRI measures of brain aging, JAMA, 302, pp. 2565–2572.

Ligthart, S.A., Moll van Charante, E.P., van Gool, W.A., Richard, E. (2010) Treatment of cardio-vascular risk factors to prevent cognitive decline and dementia: a systematic revie, Vascular Health & Risk Management, (6), pp. 775–85.

Lincoln, P., Fenton, K., Alessi, C., Prince, M., Brayne, C., Wortmann, M., Patel, K., Deanfield, J., Mwatsama, M. (2014) The Blackfriars Consensus on brain health and dementia, Lancet, May 24, 383(9931), pp. 1805-6.

Lindsay, J., Hebert, R.Rockwood, K. (1997) The Canadian Study of Health and Aging – Risk Factors for Vascular Dementia, Stroke, 28, 526–530.

Lupton, D. (1999) Risk. London: Routledge.

Lyman, K. A. (1989) Bringing the social back in: a critique of the bio-medicalisation of dementia, Gerontologist, 29, pp. 597–604.

Masi, C.M., Chen, H.Y., Hawkley, L.C., Cacioppo, J.T. (2011) A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness, Pers Soc Psychol Rev, Aug, pp. 15(3):219-66.

McCullagh, C.D., Craig, D., Mollroy, S.P., Passmore, A.P. (2001) Risk factors for dementia, Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 7, pp. 24-31.

McKhann, G.M, Knopman, D.S., Chertkow, H., Hyman, B.T., Jack, C.R. Jr, Kawas, C.H., Klunk, W.E., Koroshetz, W.J., Manly, J.J., Mayeux, R., Mohs, R.C., Morris, J.C., Rossor, M.N., Scheltens, P., Carrillo, M.C., Thies, B., Weintraub, S., Phelps, C.H. (2011) The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease, Alzheimers Dement, 7, pp. 263–9.

Milne, A. (2010) Dementia screening and early diagnosis: The case for and against, Health, Risk & Society, 12(1), pp. 65–76.

Mizutani, K., Nishimura, K., Ichihara, A., Ishigooka, J. (2014) Dissociative disorder due to Graves’ hyperthyroidism: a case report, Gen Hosp Psychiatry, Mar 19. pii: S0163 8343(14)00073-5.

Monastero, R., Mangialasche, F., Camarda, C., Ercolani, S., Camarda, R. (2009) A systematic review of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment, J Alzheimers Dis, 18(1), pp. 11–30.

Moroney, J.T., Tang, M.X., Berglund, L., Small, S., Merchant, C., Bell, K., Stern, Y., Mayeux, R. (1999) Low density lipoprotein cholesterol and the risk of dementia with stroke, Journal of the American Medical Association, 282, pp. 254–260.

Morris, J.C. (2005) Early-stage and preclinical Alzheimer disease, Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord, 19, pp. 163–5.

Morris, M.C., Evans, D.A., Bienias, J.L., Tangney, C.C., Bennett, D.A, Aggarwal, N., Schneider, J., Wilson, R.S. (2003) Dietary fats and the risk of incident Alzheimer disease, Arch Neurol, 60(2), pp. 194-200. [Erratum in: Arch Neurol. 2003 Aug;60(8):1072.]

National Audit Office (2007) Improving services and support for people with dementia, London: The Stationary Office.

Ngandu, T., Helkala, E.L., Soininen, H., Winblad, B., Tuomilehto, J., Nissinen, A., Kivipelto, M. (2007) Alcohol drinking and cognitive functions: findings from the Cardiovascular Risk Factors Aging and Dementia (CAIDE) Study, Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord, 23(3), pp. 140-9.

Ngandu, T., von Strauss, E., Helkala, E.L., Winblad, B., Nissinen, A., Tuomilehto, J., Soininen, H., Kivipelto, M. (2007) Education and dementia: what lies behind the association? Neurology, Oct 2, 69(14), pp. 1442-50.

Norton, S., Matthews, F.E., Barnes, D.E., Yaffe, K., Brayne, C. (2014) Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis of population-based data, Lancet Neurol, Aug, 13(8), pp. 788-94.

Panza, F., Frisardi, V., Seripa, D., Logroscino, G., Santamato, A., Imbimbo, B.P., Scafato, E., Pilotto, A., Solfrizzi, V. (2012) Alcohol consumption in mild cognitive impairment and dementia: harmful or neuroprotective? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry, Dec, 27(12):1218-38.

Peters, R. (2012) Blood pressure, smoking and alcohol use, association with vascular dementia. Exp Gerontol, Nov, 47(11), pp. 865-72.

Piazza-Gardner, A.K., Gaffud, T.J., Barry, A.E. (2013) The impact of alcohol on Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review, Aging Ment Health, 17(2), pp. 133–46.

Prasad, A.S. (2009) Impact of the discovery of human zinc deficiency on health, J Am Coll Nutr, 28, pp. 257–265.

Prasad, A.S. (2003) Zinc deficiency, BMJ, 326, pp. 409–410.

Ratnavalli E, Brayne C, Dawson K, et al. (2002) The prevalence of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology, 58:1615–21.

Redman, R.W., Lynn, M.R. (2004) Advancing patient-centred care through knowledge development, Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 36(3), pp. 116-129.

Rissman, R.A., Staup, M.A., Lee, A.R., Justice, N.J., Rice, K.C., Vale, W., Sawchenko, P.E. Corticotropin releasing factor receptor-dependent effects of repeated stress on tau phosphorylation, solubility, and aggregation, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, Apr 17, pp. 109(16):6277-82.

Ritchie, C.W., Ritchie, K. (2012) The PREVENT study: a prospective cohort study to identify mid-life biomarkers of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, BMJ Open, Nov 19, pp. 2(6).

Rusanen, M., Rovio, S., Ngandu, T., Nissinen, A., Tuomilehto, J., Soininen, H., Kivipelto, M. (2010) Midlife smoking, apolipoprotein E and risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a population-based cardiovascular risk factors, aging and dementia study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord, 30(3), pp. 277-84.

Saleem, A., Sophia, R. (2014) Voltage-gated potassium channel antibody-associated limbic encephalitis, Age Ageing, Jul, 43(4), pp. 583-5.

Sapolsky, R.M. (1996) Why stress is bad for your brain, Science, 273, pp. 749–50.

Scarmeas, N., Stern, Y., Tang, M.X., Mayeux, R., Luchsinger, J.A. (2006) Mediterranean diet and risk for Alzheimer’s disease, Ann Neurol, Jun, 59(6), pp. 912-21.

Schliebs, R., Arendt, T. (2011) The cholinergic system in aging and neuronal degeneration, Behav Brain Res, Aug 10, 221(2), pp. 555-63.

Skoog, I., Kalaria, R.N., Breteler, M.M. (1999) Vascular factors and Alzheimer disease, Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord, 13(suppl 3), pp. S106–S114

ofi, F., Valecchi, D., Bacci D., Abbate, R., Gensini, G.F., Casini, A., Macchi, C. (2011) Physical activity and risk of cognitive decline: a meta-analysis of prospective studies, J Intern Med, 269(1), pp. 107–17.

Sperling, R.A., Rentz, D.M., Johnson, K.A., Karlawish, J., Donohue, M., Salmon, D.P., Aisen, P. (2014) The A4 study: stopping AD before symptoms begin? Sci Transl Med, Mar 19, 6(228), pp. 228fs13.

Stern, Y., Gurland, B., Tatemichi, T.K., Tang, M.X., Wilder, D., Mayeux, R. (1994) Influence of education and occupation on the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease, JAMA, 271(13), pp. 1004–10.

Szewczyk, B. (2013) Zinc homeostasis and neurodegenerative disorders. Front Aging Neurosci, Jul 19, 5:33.

Tischler V, D’Silva K, Cheetham A, Goring M, Calton T. Involving patients in research: the challenge of patient-centredness, Int J Soc Psychiatry, 2010 Nov, 56(6), pp. 623-33

Tyas, S.L., White, L.R., Petrovitch, H., Webster Ross, G., Foley, D.J., Heimovitz, H.K., Launer, L.J. (2003) Mid-life smoking and late-life dementia: the Honolulu-Asia aging study, Neurobiol Aging, 24(4), pp. 589–96.

van der Linde, R.M., Stephan, B.C., Matthews, F.E., Brayne, C., Savva, G.M. (2013) Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study. The presence of behavioural and psychological symptoms and progression to dementia in the cognitively impaired older population, Int J Geriatr Psychiatry, Jul;28(7):700-9.

van Duijn, C.M., Hendriks, L., Cruts, M., Hardy, J.A., Hofman, A. (1991) Amyloid precursor protein gene mutation in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, Lancet, 337(8747): 978.

Vellas, B., Gillette-Guyonnet, S., Andrieu, S. (2008) Memory health clinics-a first step to prevention, Alzheimers Dement, Jan, 4(1 Suppl 1):S144-9.

van El, C.G., Cornel, M.C., Borry, P., Hastings, R.J., Fellmann, F., Hodgson, S.V., Howard, H.C., Cambon-Thomsen, A., Knoppers, B.M., Meijers-Heijboer, H., Scheffer, H., Tranebjaerg, L., Dondorp, W., de Wert, GM, ESHG Public and Professional Policy Committee. (2013) Whole-genome sequencing in health care: recommendations of the European Society of Human Genetics, Eur J Hum Genet, Jun;21(6):580-4.

Verity, C.M., Nicoll, A., Will, R.G., Devereux, G., Stellitano, L. (2000) Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in UK children: a national surveillance study, Lancet, Oct 7, 356(9237), pp. 1224-7.

Victor, M., Adams, R.D., Collins, G.H. (1971) The Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome. F.A. Davis.

Vileland, T. (2002) Managing chronic disease: evidence-based medicine or patient-centred medicine? Health Care Analysis, 10(3), pp. 289-98.

Wang, H.X., Gustafson, D.R., Kivipelto, M., Pedersen, N.L., Skoog, I., Windblad, B., Fratiglioni, L. (2012) Education halves the risk of dementia due to apolipoprotein ε4 allele: a collaborative study from the Swedish brain power initiative, Neurobiol Aging, 33(5). 1007.e1-7.

Warren, M.W., Hynan, L.S., Weiner, M.F. (2012) Lipids and adipokines as risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease, J Alzheimers Dis, 29, pp. 151–157.

WHO (Revised February 2012) Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: factsheet no 180, available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs180/en/ [accessed 12 June 2014].

Wilson, R.S., Scherr, P.A., Schneider, J.A., Tang, Y., Bennett, D.A. (2007) Relation of cognitive activity to risk of developing Alzheimer disease, Neurology, 69(20), pp. 1911–20.

Wise J. (2014) £90m package to improve dementia care is announced in England, BMJ, 348, g1879.

Zecca, L., Youdim, M.B., Riederer, P., Connor, J.R., Crichton, R.R. (2004) Iron, brain ageing and neurodegenerative disorders, Nat Rev Neurosci, 5, pp. 863–873.

Source of the graphic in the top left corner of this page is here.

‘Whole person care’ has been done by family doctors for years. We do not need yet more managerial silos.

“No matter how busy you are, you must take time to make the other person feel important.” -Mary Kay Ash

People living with dementia are generally not kept ‘in the loop’ about major decisions in the running of their health and social care services.

Whereas some politicians clearly see some capital in promoting dementia, it is hard to distinguish whether this is a genuine interest in dementia or a need to act as a broker for the pharmaceutical multinationals.

Likewise, ‘whole person care’ has all the makings of a great slogan, raising expectations beyond a reality. The concept is, irrespective of funding mechanisms in various jurisdictions, is that you see beyond a list of clinical diagnoses.

You ‘take notice’ of a person when they’re not ill; this has become a very potent concept with realisation that many people live with conditions but are not symptomatic of any illness. And more than ‘taking notice’, you actively help with issues that can help with wellbeing (such as lifestyle, advice about enforcement of legal rights, good quality housing, access to appropriate benefits, proper design of the environment.)

My working definition of ‘personhood’ is somewhat more basic than that of Carl Jung and Tom Kitwood, whose feet I should never wish to tread on intellectually. But my definition is simply that any person living well is at ease with his or her own past, present and future, and his or her environment including community.

In my view, therefore, it is refutable that there are sources of expertise for whole person care outside the medical profession, including unpaid carers, nurses, occupational therapists, physiotherapists and speech and language t harpists, as well as other persons with dementia.

Health and social care in England currently feels like fragmented different worlds, with a complete lack of communication between them. The lack of continuity of care leads to operational problems in offering health and social care. And if you reduce people to a list of diagnoses, you ignore the past of that person.

For example, a concert pianist might have rather different views about developing rheumatoid disease in his fingers than a building site construction worker has about developing the same disease in his.

What is driving the cost of the NHS budget in England, however, in England is technology not the ageing population; half of England’s current NHS budget goes to people below the age of 65 (Iliffe and Manthorpe, 2014).

There is an important how it could be delivered. An anticipated problem is that how the ‘integrator’ will include services including the private sector as well as possibly community care units; in this rôle the integrator ends up subcontracting services, potentially subverting the original ethos of the CCG process. This is a recipe for fast tracking resources away from the State to the private sector, highly dependent on corporates acting like ‘good citizens’.

Certainly, electronic patient records shared between entities would help.

But there is a temptation, and indeed danger, that ‘whole person care’ becomes a wish list for multinational corporations; e.g. “big is best” and implementation of massive IT projects. Focusing on a person’s beliefs, concerns and expectations, however, has been done successfully for decades by many family doctors, who have been subject to the same principles of regulation over confidentiality and disclosure as relevant to IT systems. By this I mean family doctors who spent ages talking to persons and their families in various environments such as home visits, rather than doctors in modern general practice guillotined by the seven minute time slot.

The current UK Labour opposition is wishing to implement ‘whole person care’ in its next government, and it of course it remains to be seen whether they will be given a mandate for doing so.

But, if so, policy has a delicate balance to run between recognising specialist clinical care in dementia, e.g. through Admiral nurses, in England, and not creating new “silos”, e.g. whole person care nurses in dementia.

Creation of new silos from management and management consultants, apart from all else, encourages insurance-based funding mechanisms for single diseases rather than mechanisms which encourage fair treatment of the whole person in an equitable way.

The strength about the ‘whole person care’ construct is that persons have their physical health, social care and mental health needs considered in the round, with an understanding that comorbities can act both ways: physical illness can cause mental illness, and vice versa.

Whilst it might seem like an experiment in England, and could not have come at a worse time for the NHS with campaigners feeling that changes in health policy are essentially a rouse for backdoor privatisation, the approach of ‘whole person care’ is particularly relevant to dementia, and other jurisdictions, for example California, have already made good progress with it.

Is the use of GPS “trackers” for people living with dementia necessary and proportionate?

This is the introduction to “Living better with dementia: how champions can challenge the boundaries”, chapter 12, “Do GPS trackers have a rôle to play in living better with dementia?”

“We live in a ‘surveillance society’. If you happen to log in on Facebook, Facebook can identify your location exactly, and then can offer you a choice of cheap hotels there. The idea that a GPS system (“global positioning system”), as a tracker, can identify you where you are might seem like an invasion of privacy, but not much of an invasion of privacy than Facebook, arguably. And indeed a non-invasive system might be better than a method of physical restraint for certain people with dementia. It would be hard to justify a tracking device in a person who is not a candidate for physical restraint though conceivably?

Tracking for people with dementia raises strong emotions, not helped with some of the discussion acting at the extremes, such as a hypothermic person with dementia found in a ditch due to a GPS tracker. But the conflation of ‘tracking’, with ‘tagging’ as per frequent offenders in the criminal law, is an unfortunate one. At a time when there are international drives towards decreasing stigma in people with dementia, people warn about the mission creep that is offered with tracking: for example, one wonders how long it might be for a GPS tracker to become an implantable micro-chip. The word ‘tracking’ itself, however, is a misnomer, in that these trackers do not actively ‘follow’ people, but can pinpoint someone’s location through the method of ‘trilateral’. Satellite detectors happen to be there, in the same way that public telephone boxes happen to be there. Public telephone boxes take on a different atmosphere if highly illegal activity happen to be taking there, and there is a proportionate need to intervene. But intervene in what? Here we are talking about a criminal activity, rather than intervene in a person at risk of causing harm to himself or herself? The question that someone can consent to doing himself or herself avoiding being at personal harm, exercising too his or her own ethical right to autonomy, and a clear definition of consent depends on a clear definition of capacity. A human right to privacy which is inalienable albeit qualified may transcend capacity, causing further disquiet in legal circles. And, besides, people who do happen to travel beyond their physical zone might not be doing so out of any particular malice: a person with dementia may simply have problems with spatial navigation. Presumption of innocence is pivotal in the law is pivotal, and laying blame on innocent people is unacceptable – even subtlely through terms laced with innuendo such as “wandering”.

One wonders whether the legal definition of capacity across a number of jurisdictions, which depends on an “all-or-nothing” construct, can cope with those dementias where cognitive abilities fluctuate or cognitive demands vary. Is legal capacity to make a sandwich the same as capacity to write a paper on human rights? And who is best to make a decision about fitting a GPS tracker? It must surely cause concern if a caregiver would wish to fit one simply because it makes the monitoring of an individual an easier job, rather than the person with dementia wishes to be more independent. It is therefore clear that there is no right answer to GPS systems in dementia, especially as the term “dementia” itself is a portmantaneau term for lots of different clinical conditions, with different types and ‘severities’. Whether GPS trackers are necessary and proportionate for any one person living with dementia is a rather abstract question, given that there are so many different subtypes of dementia making some more prone to travel beyond their locality than others. With GPS tracking in dementia, we see yet another example where ‘one glove fits all’ approach is a dismal failure.”

The selling of dementia-related service products bears an uncanny resemblance to the selling of securitised mortgage products

There is a need for high quality dementia services in the United Kingdom. There are about one million people living with dementia currently, and there are many services which might be relevant to them: like adequate signage to improve spatial navigation, good advocacy services, good advice for ‘dementia friendly wards’, good assistive technologies, and so on.

Some of them will be regulated, such as adaptations which are in fact ‘medical equipment’. And it is in a sense the buyers’ market, in that buyers can choose which product to go for. It is a booming economy.

Everyone likes a bandwagon. A bandwagon for dementia service products might be as lucrative as a bandwagon for securitised mortgage products, particularly if there’s a “buzz” somewhere.

For six years, the basic narrative – accepted by commentators and politicians – has been that securitisation, in essence a way of transforming one type of assets into another one, was the primary reason for the global financial meltdown, especially in the US sub prime market.

But the situation there is turning out to be more complicated than at first glance. US sub prime mortgage products aside, the performance of the securitisation market to date has actually been very creditable and, in some cases, better than other, more conventional investments.

Likewise, even before the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge, it is true that there were some very creditable offerings on dementia-friendly designs and assistive technologies.

There’s now a market for dementia services, like there was for securitised mortgage products. But when they go bust, there are three options for what to do next.

Firstly, one can blame Gordon Brown.

By this mean, the current Coalition government blamed Gordon Brown convincingly for ‘crashing the car’, when patently the economies suffered in other jurisdictions not due to Gordon Brown

If these dementia services products go bust, as such there will nothing that can be done, other than a market which has burnt out.

Secondly, one can blame the buyer.

The English law has a long tradition of ‘caveat emptor’, where the buyer is expected to do due diligence of what he or she is buying. There is an added complication here in that a failure of a duty of care by a middle man, such as an advisor, might be implicated if these products go bust. This can happen for securitised mortgage products, as well as dementia services products.

Thirdly, you can blame the regulator.

You could blame the financial regulator, or even abolish it (like what happened to the Financial Services Authority). In healthcare, likewise, you could simply abolish the regulator and start again hiving off parts into various functions. But this depends on how closely the regulator has been in promoting the product to begin with.

If a regulator has failed to do due diligence, the regulator will be blamed by people who have bought the product if the product goes bust.

In theory, the financial regulator can ‘stress test’ these products, to see how these financial products behave in a real environment. The options for the regulator means assimilating as much information about the product as possible.

In the case of financial services, this might include: does the product fulfil a legitimate need? In the dementia world, a dementia service product could make it easier to promote one of the 6Cs in nursing, or to prove your commitment to person-centred care; this is helpful for ticking boxes.

But again it’s a matter of due diligence; while regulatory capture can mean substantial competitive advantage for the seller of the dementia service product, the regulator is expected to show some understanding of the validity of the product.

So what can I conclude?

Nothing much. Just hope to hell that the luck doesn’t run out for the sellers of dodgy products; this might be as catastrophic for the dementia economy world, as the world macroeconomy.

Personalised medicine, genetics and Big Data: the “New Jerusalem” for dementia?

The fact that there are real individuals at the heart of a policy strand summarised as ‘young onset dementia’ is all too easily forgotten, especially by people who prefer to construct “policy by spreadsheet”.

It is relatively uncommon for a dementia to be down to a single gene, but it can happen. And certainly, even if there might not be ‘cure’ for today or tomorrow, identification of precise genetic abnormalities might provide scope for genetic counseling. Markus (2012) argues that many monogenic forms of stroke are untreatable, and therefore, specialised genetic counseling is important before mutation testing. This could be particularly important in asymptomatic individuals, or those with mild disease; for example, potential cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) patients who have migraine but have not yet developed stroke or dementia. Mackenzie and colleagues (Mackenzie et al., 2006) published on a group of families with a clinical diagnosis of tau-negative, ubiquitin-immunoreactive neuronal inclusions (NII). The authors discussed how findings across the literature appeared to suggest that, in this particular condition, NII are a highly sensitive pathological marker for progranulin genetic mutations and their demonstration may be a way of identifying cases and families that should undergo genetic screening.

But is this genomics revolution the beginning of a “New Jerusalem” in dementia, beyond the headlines?

“Big data” refers to information that is too large, varied, or high-speed for traditional methods of storage, processing, and analytics. For example, one application of mining large datasets that has been particularly productive in the research community is the search for genome-wide associations (“Genome-Wide Association Studies (“GWAS”)). GWAS rely on analysis of DNA segments across vast patient populations to search for DNA variants associated with a particular disease. To date, GWAS analyses have identified a handful of promising genetic associations with Alzheimer’s disease, including Apo E4.

This is clearly wonderful if “money does grow on trees”, but the concern for initiatives such as these such work is resource-intensive, and diverts resources from frontline improvements in wellbeing of people living with dementia. Investors also have to be mindful of their financial return compared to the risk of such initiatives. One of the biggest complaints of proponents of “Big Data” is that data tend to be pocketed in a fragmented, piecemeal fashion.

As the McKinsey Centre for Business Technology (2012) state in an interesting document called, “Perspectives on digital business”:

“The US health care sector is dotted by many small companies and individual physicians’ practices. Large hospital chains, national insurers, and drug manufactuers, by contrast, stand to gain substantially through the pooling and more effective analysis of data.”

Vast collections of genomic data obviously represent a goldmine for health providers around the world. Meltzer (2013) reviews correctly that personalized medicine been the subject of increased basic and clinical research interest and funding. Meltzer describes that a knowledge of the genetic and molecular basis of clinical heterogeneity should make it possible to more reliably predict the likely outcomes of alternative approaches to treatment for specific individuals and therefore what course of action is likely to be best for any given patient. Knowledge of personal genetic traits might allow accurate prediction of those invididuals who are most likely to experience adverse events through medication (Markus, 2012).

Both ‘Big Data’ and ‘personalised medicine’, in being couched language of bringing value to operational processes in corporate strategy, tend to lose the precise cost-effectiveness arguments at an accounting level. The new CEO of NHS England, Simon Stevens, will have raised eyebrows with the Guardian piece entitled, “New NHS boss: service must become world leader in personalised medicine” from 4 June 2014 in “The Guardian” newspaper (Campbell, 2014) . Whether the National Health Service of the UK can cope with this, with inevitable transfer of funds from the public funds to private funds, with all the talk of ‘sustainability’, is a different matter. It is difficult to predict what the uptake of personalised medicines will be, even if every patient has access to his or her personal genomic sequence in years to come. All jurisdictions have to consider whether they can justify the sharing of information for public interest overcoming concerns about data privacy and security, and ultimately this is a question of legal proportionality.

The pitch from corporate investors tend to minimise biological practicalities too. For example, it is still yet to be determined what the precise interplay between genetic and environmental factors are, particularly for the young onset dementias. And the assumption that all ‘big’ data are ‘good’ data could be a fallacy. There are 1000 billion neurones in the human brain, and it is well known that not all neuronal connections between them are ‘productive’; in fact a sizeable number are redundant. Heterogeneity in genetic sequences might be meaningful, or utterly spurious, and it could be a costly experiment to wait to find out how, when there are more pressing considerations about both care and cure.

But is this genomics revolution the beginning of a “New Jerusalem” in dementia, beyond the headlines?

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) is the second most common cause of dementia in individuals younger than 65 years (Ratnavilli et al., 2002). It is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characteristically defined by behavioural changes, executive dysfunction and language deficits. The behavioural variant of FTLD is characterised in its earliest stages by a progressive, insidious change in behaviour and personality, considered to reflect underlying problems in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (Rahman et al., 1999). FTLD has a strong genetic background, as supported by positive family history in up to 40% of cases, higher than what reported in other neurodegenerative disorders and by the identification of causative genes related to the disease (Seelaar et al., 2011). The notion that genetic background might affect disease outcomes and rate of survival, modulating the onset and the progression of the pathological process when disease is overt (Premi et al., 2012). Given the consolidated role of genetic loading in FTLD, the likely effect of environment has almost been neglected.

Only recently, it has been reported that modifiable factors, i.e. education and occupation, might act as proxies for reserve capacity in FTLD. Patients with a high level of education and occupation can recruit an alternative neural network to cope better with cognitive functions (e.g. Borroni et al., 2009; Spreng et al., 2011). But the search for treatments for particular types of dementia based on their underlying genes and genetic products is arguably not an unreasonable one. A good example is provided by the Horizon Scanning Centre of the National Institute for Health Research of NHS England in September 2013 (NIHR HSC ID: 8239): leuco-methylthioninium, which is a “tau protein aggregation inhibitor”. It acts by preventing the formation and spread of neurofibrillary tangles, which consist of aberrant tau protein clusters that aggregate within neurons causing toxicity and neuronal cell death in the brain of patients with certain forms of dementia. Leuco-methylthioninium is a stabilised, reduced form of charged methylthioninium chloride. The clinical trials for this are under way. The medication at the time of writing may or may not work safely.

No. This genomics revolution the beginning of a “New Jerusalem” in dementia, especially when social care is on its knees.

References

Borroni B, Premi E, Agosti C, Alberici A, Garibotto V, Bellelli G, Paghera B, Lucchini S, Giubbini R, Perani D, Padovani A. (2009) Revisiting brain reserve hypothesis in frontotemporal dementia: evidence from a brain perfusion study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord, 28, pp. 130–135

Campbell, D. (2014) New NHS boss: service must become world leader in personalised medicine, The Guardian, 4 June. http://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/jun/04/nhs-boss-world-leader-personalised-medicine.

Mackenzie, I.R., Baker, M., Pickering-Brown, S., Hsiung, G.Y., Lindholm, C., Dwosh, E., Gass, J., Cannon, A., Rademakers, R., Hutton, M., Feldman, H.H. (2006) The neuropathology of frontotemporal lobar degeneration caused by mutations in the progranulin gene, Brain, 129(Pt 11), pp. 3081-90.

Mendez, M. (2006) The accurate diagnosis of early-onset dementia. Int J Psychiatry Med, 36(4), pp. 401– 12.

McKinsey Centre for Business Technology (2012) Perspectives on digital business.

Rahman, S., Sahakian, B.J., Hodges, J.R., Rogers, R.D., Robbins, T.W. (1999) Specific cognitive deficits in mild frontal variant frontotemporal dementia, 122 (Pt 8), pp. 1469-93.

Ratnavalli E, Brayne C, Dawson K, Hodges JR. (2002) The prevalence of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology, 58(11), pp. 1615-1621.

Spreng, R.N., Drzezga, A., Diehl-Schmid, J., Kurz, A., Levine, B., Perneczky, R. (2011) Relationship between occupation attributes and brain metabolism in frontotemporal dementia, Neuropsychologia, 49, pp. 3699–3703.

No pledge is too small. Please sign up for my @DementiaFriends session on Aug 14 in Central London.

The aim of ‘Dementia Friends’ is to sign up people who wish to learn about dementia.

There are probably close to one million people living with dementia in the UK. There are probably also somewhere in the region of a hundred different causes of ‘dementia’.

These diseases of the brain cause problems in thinking – not necessarily memory, could be language, planning, complex visual perception, attention, decision making, distorted ideas.

Sadly, there’s a lot of misinformation about dementia.

This initiative from the Alzheimer’s Society, supported by Public Health England, is a remarkable initiative from the current Government to educate the general public on dementia. With greater education, it is hoped, barriers in society which lead to stigma and discrimination might be broken down.

Stigma is particularly significant, as stigma can lead to social isolation.

I will be giving an information session at BPP Law School on 14 August 2014, at 3.45 pm. On the day, you’ll need to ask the main Reception which room we’re in.

Whilst I am an academic in dementia, the session will be very basic. The aim is to explain in a completely unthreatening way some basic facts about dementia.

Because of the security of the law school in Central London, you’ll need to sign up in advance.

You’ll have to register on the @DementiaFriends website [here], but once you’ve done so you can register for the event here.

The people who attend are normally well informed, friendly and enthusiastic. You’ll be invited to have a badge should you wish to become a ‘Dementia Friend’.

More importantly, you’ll be asked to think of a commitment and action, and no pledge is too small.

It might be for example to ask your local paper to avoid using the term ‘dementia sufferers’, as this term might exacerbate stigma.

An example is here.