The political accusation, in case you have not heard it, is that structures of the main government can insufficiently promote prosperity and not pull people out of poverty. This may be couched in terms of a ‘civic conservatism’ analysis, but provokes rightly for me a need not to shy away from certain difficult issues. It would never be a stated outcome of English dementia policy to promote a ‘dependency culture’, and such accusations are fraught with political and financial overtones.

Change is not necessarily progress, but there was much to be cheerful about in Phillip Blond’s analysis of the potential beneficial outcome of devolution, from the NHS Confederation yesterday. Simon Stevens quoted David Bowie in his speech, but, especially since the media were pump primed with the £22 of ‘efficiency savings; but I wonder whether William Gibson would’ve been more appropriate – “The future is already here. It’s not evenly distributed yet.” There is no doubt that generalism is a highly valued specialism in itself, but I think this is the one area in policy where we must not denigrate diversity in talent. Controlling one’s destiny, control or agency, in living better with dementia must be an outcome many of us should wish to embrace?

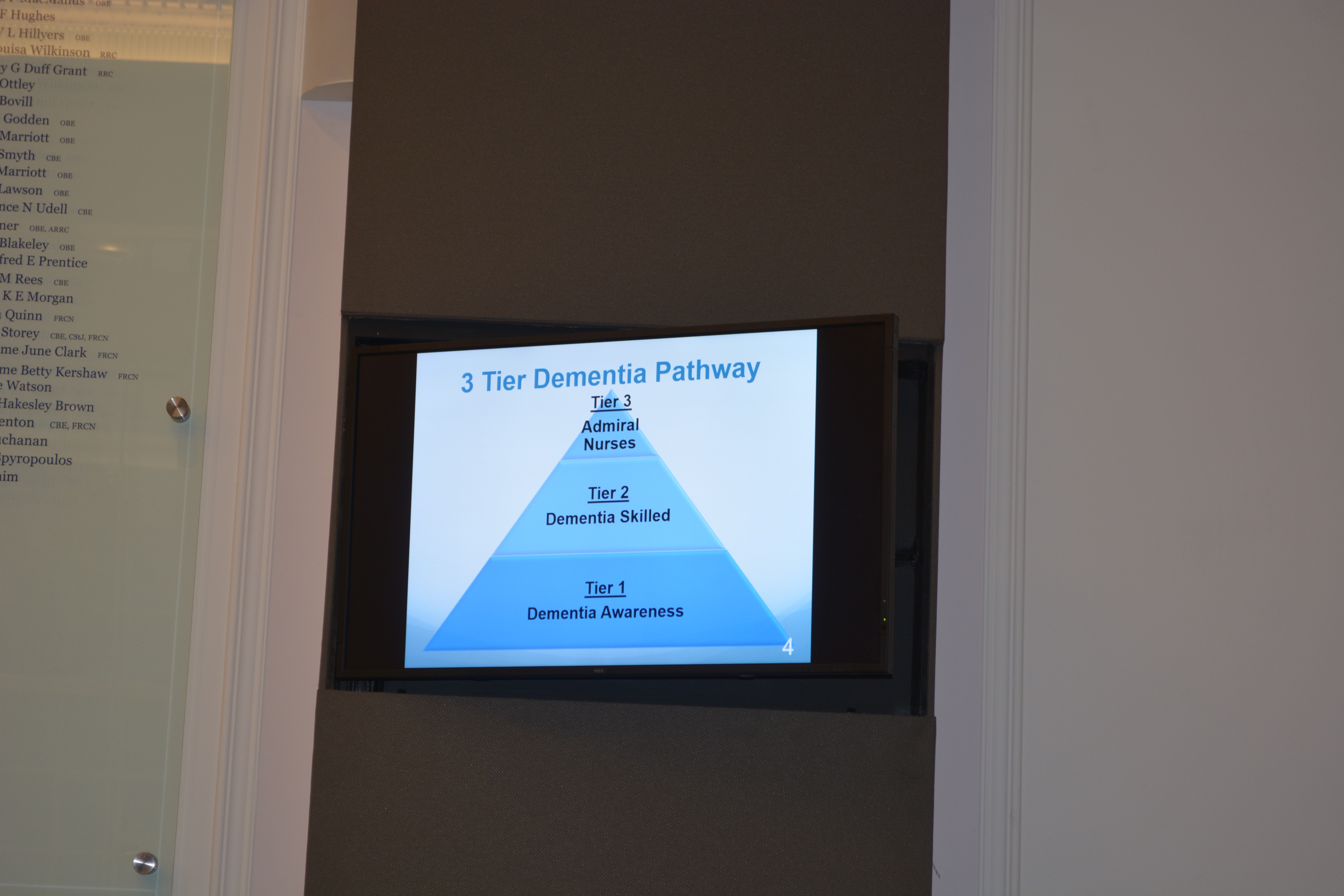

Whilst ‘awareness’ of dementia for example is important, it’s also great that we can have specialist Admiral dementia clinical nurses who can do the ‘heavy lifting’ in dementia-specific issues, such as care and support of the needs of carers, initial diagnosis, end of life care, clinical issues (such as eating, incontinence, mobility). Such an approach might be illustrated in this policy ‘pyramid’.

And it must be a concern that certain institutions exert a new monopolistic power, it seems, on health and care. Even a small number of entities can collude together (oligopolies) to produce monopolistic effect. We have the exactly the same parallel in providing of health and care, if hospital services collude amongst themselves to drown out the wonderful pro-active work that could be done in primary care to encourage health and wellbeing.

This of course is highly desirable in changing a ‘fragmented illness service’ into a ‘national health service’. Before mobilising a social movement into actions, one is obliged I feel to articulate the narrative carefully to begin with. Such a movement may be at best ‘leading from the edge’, but certainly involves working with other people, not being seen as a ‘pain in the arse’, and not merely heckling from the sidelines. I think all mainstream political parties have been keen to promote ‘choice’, and we see this particularly in the policy strand that is personal budgets. But I think often we ignore of who is actually in control; patients may not necessarily know they’re pawns in a global power game when they’re prescribed a statin not engaged in a dialogue about healthy diet. A healthy diet may help with your obesity as well as your headline figure of cholesterol?

Also, it may be possible to construct a microcosm of members of society working with each other in collective action, rather than all having individual monopolistic relationships with the State, in a devolved environment. Clinical specialist nurses should not viewed as an outpost of the State, I feel, but part of this same conversation that people with dementia and carers want. They should be the power brokers between parties, as they already are between statutory and non-statutory services, but also as knowledge brokers in communities of practice exerting much education and training power.

But the bottom line is that you can’t have control sadly unless things are properly funded. We need a commitment that these cash injections will start now not in five years time, for example. I asked Dr Peter Carter, RCN general secretary and Chief Executive, earlier this week whether there is a rôle for specialist nurses in the new English dementia strategy. Peter said ‘very much so’, then strongly explained how investing in the nursing workforce was better than short-sighted measures. I had previously had this conversation with Prof David Croisdale-Applebly, Chair of Skills for Care, after one of the sessions in the ‘Admiral nursing conference’ earlier this week at the Royal College of Nursing. David explained that it was also important to make the commissioning case carefully, as well as the clinical one, and that power would come through evidence. David of course was influential in establishing the authority of NICE, and indeed I went on my policy high horse about the need for such regulatory capture to command social prescribing. David emphasised that the case could be made for clinical nursing specialists could be made out at a national not just local level, with levers such as QUIP for example.

A distributed authentic leadership, with the voices of people with dementia and carers easily heard above the ‘noise’ is King. It’s all too easy to be entrenched in an impenetrable haze of jargon and terminology such as ‘new models of care’, but the idea that people with dementia and carers have more control over the management of their wellbeing and medical needs is for me a very attractive one. And one should not pull away support, as traditionally described, for medical including psychological needs. This should not be absolving responsibility from the NHS, particularly if viewed as the NHS ‘not being able to afford it’. Self management, however activated, with the right information is not just the domain of ‘the right’. But this is an acknowledgment that a person’s wellbeing needs might be much greater than those provided from the health and care services only.

Sources of inequality, such as housing or transport, have to be put into the mixer, but this will be possible at a level where people in society and communities can indeed communicate effectively with one another. The problem with the traditional alternative is that it can vastly restrict what is the policy offer, which I feel is detrimental to promotion of living better with dementia. Care homes, where there are over 400,000 residents, many of whom are living with dementia, are not to be viewed in isolated, but part of the wider health and care system, which should be funded much better than it is currently.

Personal control over wellbeing needs to be a focus in future English dementia policy, and should be a policy aim rightly in itself. It can never be presented simply in terms of ‘saving money’. This will not engage the hearts and minds of the public. And whilst the phrase ‘there is no such thing as society’ has been widely discussed, it is clear to me that people with dementia and carers do need to be given the tools to speak to one another, and not just been in contract with a limited number of ‘providers’, to bring about an organic progress in English dementia policy.