“The biggest disease today is not leprosy or tuberculosis, but rather the feeling of being unwanted, uncared for and deserted by everybody” Mother Theresa

I cannot recommend highly enough this account of loneliness in the context of primary care by Dr Jonathon Tomlinson in his powerful blog ‘A better NHS’.

In this, loneliness is a separable issue from whether a corporate can secure advantage by being ‘dementia friendly': it is an important social construct.

Earlier year in a prominent medical journal, it was reported that feeling lonely rather than being alone is associated with an increased risk of clinical dementia in later life and can be considered a major risk factor that, independently of vascular disease, depression and other confounding factors, deserves clinical attention.

Social care for dementia in the real world, in England, is now on its knees. The reality, as a result of deliberate budget cuts from the current admnistration, is quite gruesome.

The campaign against stigmatising stereotypes of people with dementia is a worldwide one.

And yet Norman Lamb frontloaded a standard shill for the Alzheimer’s Society ‘dementia friendly communities’ programme with an elaborate fictional description recently with an elaborate description of a bed-wetting confused person. Such negative propaganda severely runs the risk of further evaporating goodwill for the Alzheimer’s Society.

Lamb comments, “But dementia can be a cruel condition, both for those who have it and for the people who love and care for them.”

It is hard to know precisely what this ‘shock doctrine’ is supposed to achieve, other than to inject a feeling of fear and moral panic for readers of the Guardian. But the article is an extremely manipulative one. It identifies a really important social issue, but makes no room for discussion for anything other than a discussion of the Alzheimer’s Society and their ‘dementia friendly communities’ programme.

The phrase, “So we need an assault on the twin epidemics of dementia and loneliness”, needs to have a big health warning on it. The number of cases of England for dementia has been falling in the last two decades, according to carefully executed research from Cambridge.

Lamb comments, “One million [dementia friends] are expected to be recruited by 2015.” But who’s doing the expecting? What are the penalties for not reaching this particular target?

“More than 50 cities, towns and villages are already taking local action to become dementia friendly.” But Torbay has been dementia friendly for years, but not on the list of Government-approved dementia friendly communities as it has not participated in the scheme run by the Alzheimer’s Society.

If you’ve been on a ‘Dementia Friends’ course, you can’t tweak it a bit and call it your ‘Dementia Friends’ course (apart from anything else as it is protected by a trademark on the UK register.)

There’s the bind. This exclusivity exists because one more ‘dementia friend’ somewhere is one fewer ‘Dementia Friend’ on the official scheme.

This can’t be called anything else but exclusivity.

So Norman Lamb has used a discussion about isolation in dementia to encourage exclusive behaviour. This makes us a laughing stock in our English dementia policy in the eyes of the rest of the world potentially.

Lamb refers to this scheme thus: “All of this should be just the start, the beginning of a massive social movement.”

But how organic is this ‘massive social movement’? The answer is not at all.

It is known that the £2.4 million programme is funded by the Social Fund and the Department of Health. And an eye-watering amount of money has been spent by Public Health England on this marketing campaign just gone as reported here, also to promote “Dementia Friends”.

Clearly not everyone is benefiting from local commissioning decisions to promote dementia. And these decisions have had a catastrophic effect on social interactions for some people with dementia, under the lifetime of this parliament.

For Norman Lamb to pop up and complain about loneliness in dementia having promoted this policy actively in England would it be like a Tory MP complaining his local law centre had suddenly shut down.

Earlier this year, a popular day care centre for people with dementia was reported as closing down. Staff at Mundy House day care, in Church Road, Basildon, were left devestated. Larchwood, the firm which runs the centre and adjoining residential home, claims the day care facility is not making any money.

Meanwhile, last year, a council was considering plans to close up to seven centres providing specialist care for older people suffering from dementia. East Sussex County Council’s cabinet were reported as set to discuss proposals which could see the closure of a number of centres providing day services for older people in Lewes, Bexhill, Hailsham, Crowborough and Hastings.

And, simultaneously at the other end of the country, a residential care home and day centre for elderly and vulnerable adults look certain to close in a shake-up. Plymouth City Council said Lakeside in Ernesettle and St George’s in Stonehouse were to be shut. The council said it was under financial pressures and numbers using the buildings were dwindling. It admitted that some staff would lose their jobs.

But ‘dementia friendly communities’, regulated by a strict standards protocol, or a badge of ‘Dementia Friends’, encourage exclusivity. Lamb in his article makes no attempt to widen the discussion to other possible means of inclusion.

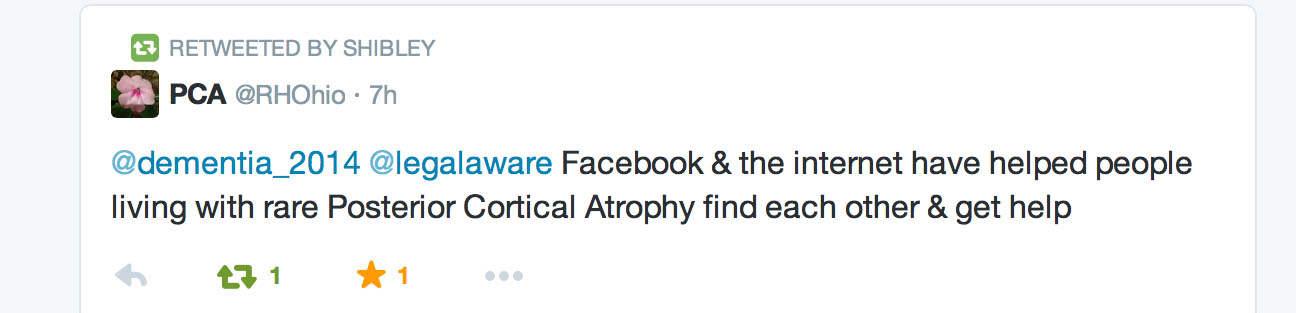

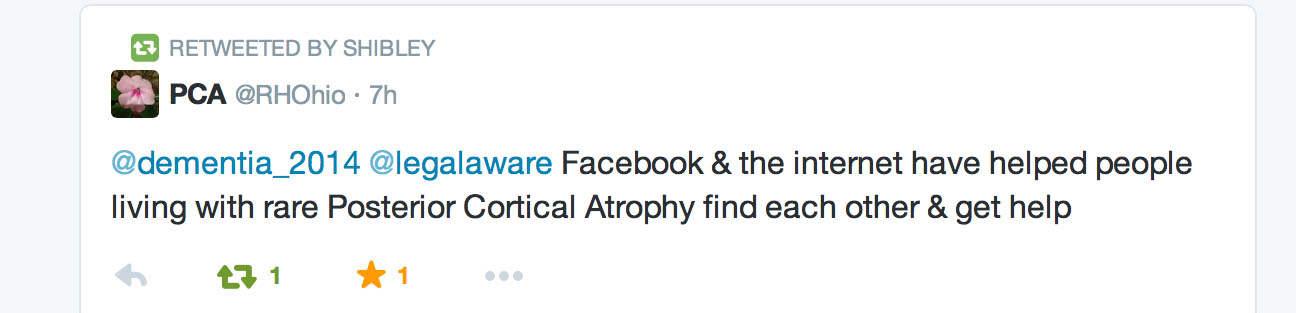

Here’s a valid approach, for example, involving the social media, from Lee on the popular “Dementia Challengers” platform:

“If you care for a relative with dementia life can seem very isolating. Carers sometimes live in a bubble, the roundabout of caring, sorting out finances, juggling family responsibilities and struggling with the challenge of keeping their relative safe, comfortable and happy. There may be issues such as family members not doing their part, or the carer may also have paid employment, young children or grandchildren to care for, or their own health issues. Many of the carers who contact me express their frustrations at feeling alone and unsupported.”

“Social media can be a great way to find other carers, and there’s a wonderful community on Twitter who support each other, share tips and good practice and lighten the day with comments, photos and light-hearted banter. If you are not already connected to the dementia challengers, I’d recommend you spend some time finding out how to use social media so that you can connect with this group of people. It’s easy to dip in and out of conversations when you have the time, or to use that five minute breather between other responsibilities to catch your breath and talk to someone in the same or a similar situation. Here are some tips about how you can use Twitter and Facebook to engage with other carers.”

And – providing supportive evidence for Lee’s argument – is a tweet by someone with familiarity with a rarer type of dementia, known as “posterior cortical atrophy”.

And, if loneliness is so valued by Norman Lamb and colleagues, shouldn’t funding be flooding in for initiatives such as the Healthy Living Club in Stockwell? The group meets for four hours each week for a programme of activities as a focus for the local community, to promote the mental and physical wellbeing of those people well with dementia. Each meeting is run as a social event, which people attend to meet each other, have a good time and share experiences. The Club is run with a team of volunteers and some sessional contributors, led by a paid co-ordinator. It is seen as a blue-print for future dementia care in the community.

Finally – we do know that David Cameron has genuine problems with the ‘C’ word – that is, “caregivers”. He recently managed to get through an entire answer in Prime Minister’s Questions, on zero-hours contracts, in the care industry without mentioning specifically ‘carers’ or ‘caregivers’. But if they are invisible as the army of millions without whom dementia care in England would implode, would be a big surprise if their loneliness too was completely ignored?