Without the work of unpaid carers, the formal care system would be likely to collapse. Some feel that the State gets a “very good deal” out of this current system. The ongoing support from unpaid carers will be a particular issue for the care system in the future, as changing demographic patterns, shifts in family composition, labour force participation and increased geographical mobility will affect the availability of the unpaid care workforce. There are also significant issues emerging in care work.

It can be argued that some carers in dementia, whether unpaid carers or paid care workers, are perceived rather unfairly by society, and this is a matter of real national concern. The issue of researching personalised medicines, and pooling clinical drug trial data, across a number of different jurisdictions, is a curiously international phenomena. It feeds into the ‘big is better’ narrative, which is of course a key aspect of why large multinational companies like ‘Big Data’. But converting our response to dementia to a solution for Big Pharma is not solely the answer. The answer is not simply ‘Big Dementia’, much as that might be attractive for the corporates. It is just as crucial to consider who cares about dementia carers. The two are not necessarily mutually exclusive of course. In an ideal world, we should like to offer the best care for people with dementia, as well as effective symptomatic treatment as well as a cure. However, it’d be a disaster if we could hold our hands up, and say that we could in all reality offer neither. As the international economies recover after the global financial crash, caused by the effects of poor global regulation of securitised mortgage products, it might seem fitting that the international landscape can be tweaked to make dementia profitable for Big Pharma. However, it is clear that our own national parliament, in the recent ‘dementia care and services’ debate on 7 January 2014, wishes to have a frank and sincere debate about who cares for the carers. As a society, this is dependent on economics within our control. If people need to talk about about the ‘cost’ of dementia relentlessly, there might be an equal and opposite need to talk about the value of carers; and this needs to be a national debate.

The usual tired mantra from politicians would of course be trotted out, particularly from those of a certain political inclination, that as the economy improves our living standards will improve. But it has been a concern of all main political parties that living standards for the many are not expected to rise as the economy recovers. In this jurisdiction, there’s a particular phenomenon of how the very wealthy seem to have been relatively immune from the global financial crash. This ‘cost of living crisis’ has been partly attributed to big corporates colluding legally to maintain prices to promote shareholder dividend rather than customer value. In England, the Health and Social Care Act (2012) was legislated by the current government to promote a quasi-market in the NHS in England. The aim was to introduce competition, bolster an economic market regulator, and to produce a mechanism for fast managed decline of ‘failing’ NHS Foundation Trusts. Clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) and health and wellbeing boards were also introduced new parts of the NHS in England. CCGs plan and buy local health services, while health and wellbeing boards influence the local decisions that shape health, public health and social care. In this new political and socio-economic landscape, it has been particularly striking, but encouraging, that the shared vision of the “Dementia Action Alliance” is of an England and Wales where the health and wellbeing of carer of a person with dementia are of equal priority to those of the person for whom they care. Ideally, for competition to thrive, it should not be in the hands of a few corporates and corporate-like charities, but all stakeholders should be given a fair slice of the action.

The wellbeing of carers of dementia in England is related to both its national economy and law, and this is something which is not within the powers of the G8 arena. In keeping with previous Conservative governments, George Osborne has warned that “self-defeating” increases to the minimum wage could “cost jobs”, and John Major, the Prime Minister 1990-7 had argued strongly the dangers of the national minimum wage. Many of the same arguments are likely to resurface as the UK Labour Party will undoubtedly raise the importance of the “living wage”, prior to the general election to be held on May 7th 2015. Cabinet ministers including Business Secretary Vince Cable and Work and Pensions Secretary Iain Duncan Smith are reportedly pressing, currently, for an “above-inflation rise” of 50p or more. Mr Osborne said he too wanted to see the £6.31 hourly minimum wage rise, but he said it should be left to the Low Pay Commission to set the appropriate level.

As Norman Lamb said in the parliamentary debate the other day, “We ask carers to do some of the most difficult work that one can ever imagine but the rewards and the training and support they get is minimal.”

An emerging political consensus has promisingly emerged that “we can never get good care on the back of exploiting very low-paid workers”, as Lamb put it. It turns out that carers are currently paid the national minimum wage if they are lucky. That is, of course, a breach of the minimum wage legislation. According to an authoritative study Dr Shereen Hussein, of King’s College London, estimates that there are between 150,000 and 220,000 care workers in this position. And this is using conservative assumptions – the real number could be higher. The flouting of national minimum wage has, however, become alarmingly widespread. There are a variety of employment practices that result in the minimum wage being circumvented, the most common of which is when councils sign contracts with private providers who recruit staff to provide short slivers of care in the home. A quarter of an hour can be all that a care worker gets to wash, change, feed and talk to someone with dementia. Dignity for the client is often the first casualty: a variety of groups representing the vulnerable, as well as some of the more scrupulous employers, fear that rushed care contracted by the minute often means inadequate care. Previous findings suggest almost half of councils still set 15 minutes as their minimum time slot.

Furthermore, many paid care workers are on zero-hours contracts. Unison’s ethical care charter aims to put an end to poor pay and working conditions in home care services. Under the charter, for example, Islington council has agreed to implement the charter’s main principles of getting rid of zero hour contracts, ensuring travel time is counted in employees’ paid hours and implementing the London living wage, as well as setting up occupational sickness schemes. Islington, alongside Southwark council, has been an early adopter of the recommendations put forward by Unison in the their report into home care. Published in 2012, the report found that good carers were being lost to “easier jobs that pay more, like in supermarkets” after finding themselves unable to support their family on an inadequate and unreliable salary.

Many paid care workers also do not get paid for travelling between the appointments they undertake, but clearly care workers must be paid when they are travelling from one home to another. Furthermore it is common for remuneration systems to pay only pay per minute actually spent with clients, not the travel time between them. Dozens of these work-related journeys could be made each week as it’s a core part of the job. Not being paid for this time means those who care don’t get paid for a full day’s work.

It is also important for councils commissioning care work to be absolutely clear with those they contract with that they expect total compliance with the law. If a council is commissioning in a way which almost becomes complicit in a breach of the law, that is completely unacceptable. On the other hand, NHS Wiltshire has commissioned an “outcomes based continuing healthcare service” designed to improve quality, reduce cost and link up with social care – but which completely restricts patient choice. The “Help to Live at Home” service has been commissioned jointly with Wiltshire Council. Contracts for the £23m service. The provider a patient receives will depend on where in the county they live. All health and social care services will be delivered by that provider and payment will depend on achieving a set of agreed outcomes.

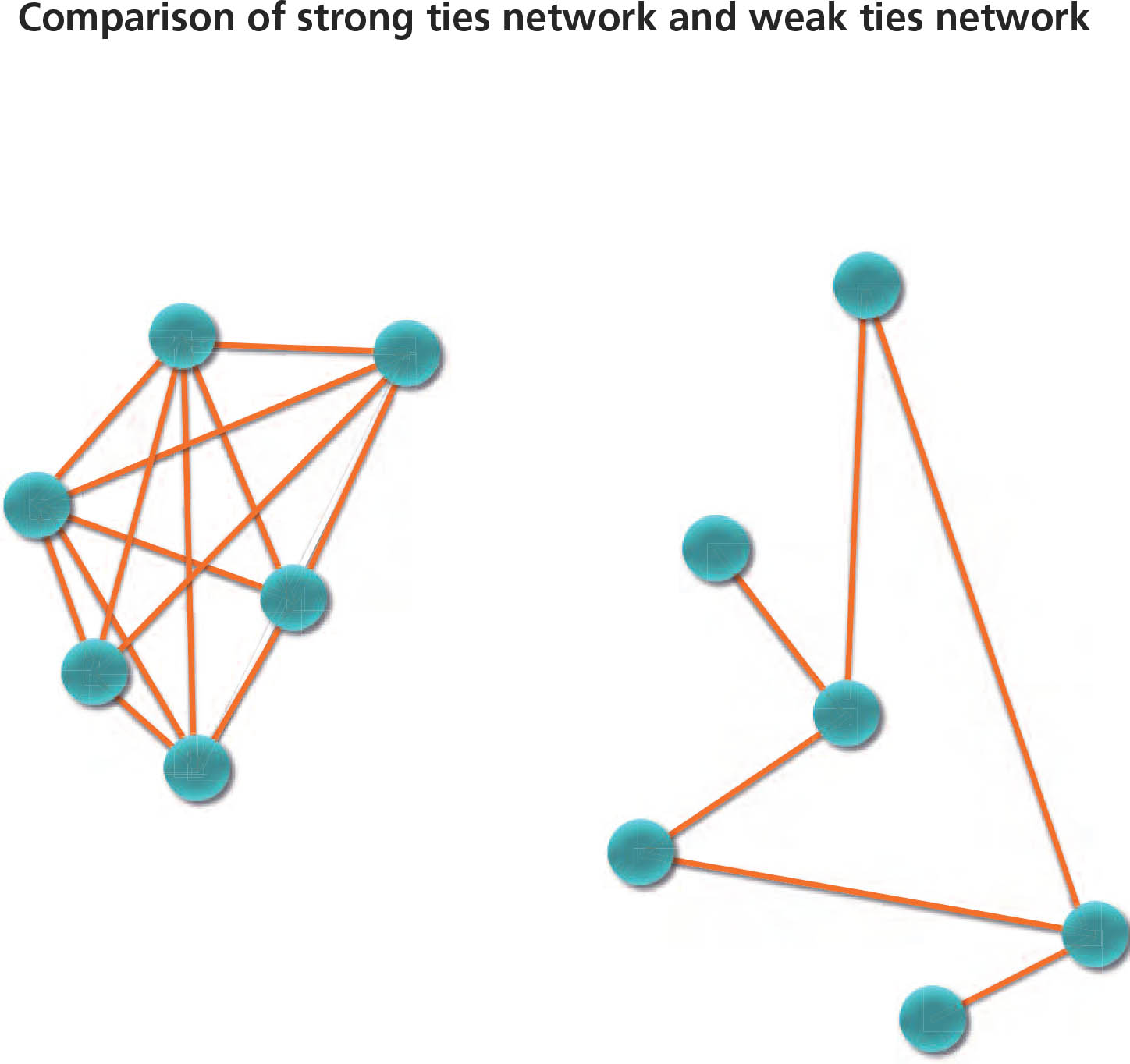

There is a big difference between “care workers” and “unpaid carers”. A phenomenon worth keeping an eye on is that of “family caregiving” which has been on an upward trend in various jurisdictions, in part due to the economic recession. Some families lack the financial capabilities to pay professional caregivers. In fact, a huge group of carers comprise the “unsalaried family caregivers”. Family caregivers of people with dementia, often called the “invisible second patients”, are critical for people living with dementia. The effects of being a family caregiver, can be both positive and negative, with high rates of burden and psychological morbidity as well as social isolation, physical ill-health, and financial hardship. Indeed, it is mooted that comprehensive care of a person with dementia can include building a partnership between all health professionals and family caregivers. Many family caregivers of people with dementia might also employed, of whom many have reported that they missed work; a proportion may have even that turned down promotion opportunities or given up work to attend to caregiving responsibilities. There is furthermore no doubt that the benefit system is confusing, and it had been hoped that universal credit would be a method of simplying that. If you care for someone with dementia, you are normally advised to check that you are both getting all the benefits and tax credits you are entitled to. For example, you may be able to claim Personal Independence Payment or Attendance Allowance for the person with dementia, and Carer’s Allowance for the carer. You, or the person you look after, may be entitled to a discount on your council tax. Again, the situation can be complicated, and many people get simply put off from applying for the benefits for which they could be entitled due to sheer complexity and/or lack of guidance.

So, how will we eventually know when carers are being looked after? We will hear that carers of people with dementia are confident that their own health and wellbeing needs and requirements are recognised and supported, so that no carer feels alone, and are given regular breaks. This is in keeping with how local and national guidance for working time should be implemented anyway. Carers of people with dementia are also recognised as essential partners in care, assuming an approach which could be best called “coproduction”. Furthermore, carers of people with dementia would also have access to expertise in dementia care for information, advice, support and co-ordination of care. The “Dementia Action Alliance” has been the coming together of over 800 organisations to deliver the National Dementia Declaration; a common set of seven outcomes informed by people with dementia and their family carers. The Declaration provides an ambitious and achievable vision of how people with dementia and their families can be supported by society to live well with the condition

It would be incredibly valuable to have carers have a voice on CCGs and health and wellbeing boards, especially since commissioners are supposed to be promoting wellbeing pursuant to the Care Bill currently being discussed in the House of Commons and the House of Lords. The demands of caring for someone with dementia are great and many carers say they feel totally unsupported. How to include unpaid care workers in this commissioning debate is undoubtedly a difficult issue, but one which simply cannot be ultimately parked for convenience.

“Big Dementia” may not provide all of the answer, unless care is combined with cure.