My close friend and colleague, Kate Swaffer, wrote an article this morning in Australia on being diagnosed with dementia vs ‘suffering’.

I strongly recommend it to you here.

This was an exchange of ours this morning on Facebook.

This topic has always caused heated exchanges for all of us.

I hope you can bear with us, as none of us mean any offence in this.

I think part of the issue is that, further to ‘once you’ve met one person with dementia, you’ve met one person with dementia’, our different views of that person with dementia can vary quite widely too.

Our discussions of ‘Living well with dementia‘ continue..

“Happy”

It might seem crazy what I’m about to say

Sunshine she’s here, you can take a break

I’m a hot air balloon that could go to space

With the air, like I don’t care baby by the way[Chorus:]

Because I’m happy

Clap along if you feel like a room without a roof

Because I’m happy

Clap along if you feel like happiness is the truth

Because I’m happy

Clap along if you know what happiness is to you

Because I’m happy

Clap along if you feel like that’s what you wanna do[Verse 2:]

Here come bad news talking this and that, yeah,

Well, give me all you got, and don’t hold it back, yeah,

Well, I should probably warn you I’ll be just fine, yeah,

No offense to you, don’t waste your time

Here’s why

[Chorus]

Hey, come on

[Bridge:]

(happy)

Bring me down

Can’t nothing bring me down

My level’s too high

Bring me down

Can’t nothing bring me down

I said (let me tell you now)

Bring me down

Can’t nothing bring me down

My level’s too high

Bring me down

Can’t nothing bring me down

I said

[Chorus 2x]

Hey, come on

(happy)

Bring me down… can’t nothing…

Bring me down… my level’s too high…

Bring me down… can’t nothing…

Bring me down, I said (let me tell you now)

[Chorus 2x]

Come on

Norman (@norrms)

Kate (@KateSwaffer)

“Stop using stigma to raise money for us”, says a leading advocate living well with dementia

Let me introduce you to Dr Richard Taylor, a member of the Dementia Alliance International living well with dementia, in case you’ve never heard of Richard.

“We shouldn’t be put on ice”, remarks Taylor.

“Or when we shouldn’t be put in a freezer, when we our caregivers go on holiday. We too should take a vacation from our caregivers.. enjoy the company of other people with dementia and enjoy their company.”

Dr Taylor had explained how there is a feeling of camaraderie when people living with dementia meet in the room. This is somewhat different from an approach of people without dementia being ‘friendly’ to people with dementia, assuming of course that you can identify reliably who the people with dementia are.

We are now more than half way though ‘Dementia Awareness Week’, from May 18 – 24 2014. Stigma, why society treats people with dementia as somehow ‘inferior’ and not worth mixing with, was a core part of Dr Taylor’s speech recently at the Alzheimer’s Disease International conference held this year in Puerto Rico.

He has ‘been going around for the last ten years, … talking to people living with dementia, and listening to them.”

That’s a common ‘complaint’ of people living with dementia: other people hear them, but they don’t listen.

“Stigma defines who we are.. not confined to the misinformed media, or the ‘dementia bigots’. Stigma is within all of us. When I heard my diagnosis, I cried for weeks… I’d never heard of dementia or Alzheimer’s disease, but it was the stigma inside me.”

Commenting a new vogue in dementia care, which indeed I have written about in my first book on living well with dementia, Taylor remarks: “We’ve now shifted to ‘person-centred care’. I think that’s a good idea. I always ask the caregiver who that person was centred was on previously. But I do that because I know I can a bit of a smart-arse”

“The stigma is in the very minds of people who treat us.”

“But you actually believe we are fading away… and we are not all there… it is not to our benefit.”

“The use of stigmas to raise awareness must stop right now.”

” Very little attention is paid to humanity of people living with dementia.. The use of stigma to raise awareness and political support must stop. We must stop commercials with old people.. which end with an appeal for funds. That reinforces the stigma. That comes out of focus groups with a bunch of people they want to focus on.”

“What would make you give money to our organisation? An older person or a younger person… We had a contest in the United States of who should represent “dementia”. The lady who won was 87-year old man staring into the abyss with a caregiver with a hand on her shoulder…”

“Telling everybody with dementia that they’re going to die is a half-truth. The other half without dementia are going to die too. Making it sounds as if people are going to die tomorrow scares the life out of people… scares the money out of people.”

But it seems even the facts about dying appear to have got mixed up in this jurisdiction. Take for example one representation of the Alzheimer’s Society successful Dementia Awareness Week ‘1 in 3 campaign’.

This was a tweet.

But the rub is 1 in 3 over 65 don’t develop dementia.

Approximately 1 in 20 over 65 have dementia.

It’s thought that by the age of 80 about one in six are affected, and one in three people in the UK will have dementia by the time they die.

There was a bit of a flurry of interest in this last year.

Neither “Dementia Friends” nor “Dementia Awareness Week” can be accused, by any stretch of the imagination, of ‘capitalising on people’s fears”.

And the discomfort by some felt by speaking with some sectors of the population is a theme worthy of debate by the main charities.

Take this for example contemporaneous campaign by Scope.

But back to Richard Taylor.

“How are you going to spend the rest of your lives? Worrying about how you’re going to die, or dying how you’re going to live?”

“I believe there is an ulterior motive.. to appeal to our fear of dying.”

“Stop using the fear of us dying to motivate people to donate to your organisations. It makes us mad and complicates our lives more than it needs to be.”

“The corruption of words to describe people who live with dementia and who live with us must stop.”

Dr Richard Taylor argues that the charities which have worked out how best to use manipulative language are the dementia charities.

“The very people who should be stopping corruption in language are the very ones involved in… “We’re going to cure dementia” What does that mean? Or will it be a vaccine where none of you get it and we all die, and so there’s no dementia any more?”

Taylor then argues you will not find ‘psychosocial research’, on how to improve the life of people with dementia.

Consistent with Taylor’s claim, this recent report on a ‘new strategy for dementia research’ does not mention even any research into living well with dementia.

“We are heading for more cures.. we’ve set the date for it wthout defining it. If we’re going to cure it by 2025, what will I see in 2018 to know we’re on track? .. It’s corrupt language.. None of the politicians will be around.. But people with dementia will be around to be disappointed.”

Taylor notes that every article rounds off with: “And now with further investigation, there’s a hope this might do this and this might do that.”

Except the politicians and charities have learnt how to play the system. These days, in the mission of raising awareness’, a Public Health and Alzheimer’s Society project, many articles focus on ‘Dementia Friends’, and people can decide at some later date whether they want to support the Alzheimer’s Society.

Articles such as this, or this, or this, or this, or this, or this, or this, or this, or this, or this, or this, or this, for example.

They could as a long shot decide to support Alzheimer’s BRACE, or Dementia UK. Dementia UK have been trying desperately hard to raise awareness of their specialist nursing scheme, called “Admiral Nurses“.

It all begs the question is the focus of the current Government to promote dementia, or to promote the Alzheimer’s Society?

Take this tweeting missive from Jeremy Hunt, the current Secretary of State for Health in the UK:

According to Taylor, “We need to start helping for the present.”

He is certainly not alone in his views. Here’s Janet Pitts, Co-Chair of the Dementia Alliance International, who has been diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia. Janet is also keen on ‘person centred services’, ‘is very proud of the work [we] have been doing since [our] inception in June 2013′, and is an advocate.

“I am an example of where life is taken away, but where life is given back… [I want us to] live well with dementia, advocate for people with dementia, reduce stigma in dementia.”

Empowering the person living with dementia personally, with more than the diagnosis

This laid down useful foundations, many strands of which were to be embellished tactically under this Government through “The Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge”. In some ways, its major limitations were unintended consequences not fully known at the time.

The English dementia strategy is intended to last for five years, and, as the 2009-14 ‘five years’ come to an end, now is THE right time to think about what should be in the next one. Irrespective of who comes to deliver this particular one, progress has been made with the current one. I believe that across a number of different strands the focus on policy should delivering care, cure or support, according to what is right for that particular person in his social environment at that particular time.

The problems facing the English dementia strategy now are annoyingly similar to the ones which Banerjee and Owen faced in 2008. Whilst they do not have ‘political masters as such’, they can be said to have had some political success. But that should never have been the landmarks by which the All Party Parliamentary Committee, chaired by Baroness Sally Greengross, were to ‘judge’ this strategy document.

The national dementia strategy back in 2009 had three perfectly laudable aims.

The first is to change professional and societal views about dementia.

There was a perception that some Doctors would sit on a possible diagnosis for years, before nailing their colours to their diagnostic mast. So this need for professionals to be confident about their diagnosis got misinterpreted by non-clinical managers as certain doctors, particularly in primary care, being obstructive in making a diagnosis.

At the time, it was perceived that there also had to be an overhaul in the way doctors think about the disease – a quarter believe that dementia patients are a drain on resources with little positive outcome, according to a National Audit Office (NAO) in July 2007. But this has only been exacerbated, and some would say worsened, by language which maintains “the costs of dementia” and “burden”, rather than the value which people with dementia can bring to society.

Associated with this has undoubtedly been the promotion of the message that ‘nothing can be done about dementia’. Indeed, the G8 dementia summit, collectively representing the views of multi-national pharmaceutical companies and their capture within finance, government and research, spoke little of care, and focused on methods such as data sharing across jurisdictions. It’s likely corporate investors will see returns on their investment in personalised medicine and Big Data, but it is essential for the morale of persons with dementia that they are not simply presented as ‘subjects’ in drug trials (and misuse of goodwill in the general public too). Unfortunately, if elements of Pharma overplay their hand, they can ultimately become losers, an issue very well known to them.

High quality research is not simply about excellent research into novel applications of drugs for depression, diabetes or hypertension, or the plethora of molecular tools which have a long history of side effects and lack of selectivity, but should also be about high quality research into living well with dementia. This is going to be all the more essential as the NHS makes a painful transition from a national illness service back to a national health service, where wellbeing as well as prevention of illness and emergency are nobel public health aims.

This summit was presented with an ultimate aim of producing a ‘cure’ for dementia by 2025, or ‘disease modifying therapies’, with no discussion of how ethical it would be – or not be – for the medical profession to put into slow motion a progressive condition; if it happened that the condition were still inevitable. The overwhelming impression of many is that the summit itself was distinctly underwhelming in what it offered in terms of grassroots help ‘on the gound’.

The G8 dementia summit did nothing to consider the efficacy of innovations for living well with dementia, for example assistive technology, ambient assisted living, design of the home, design of the ward, design of the built environment or dementia friendly communities. It did nonetheless commit to wanting to know about it at some later date.

It did nothing to consider the intricacies of the fundamentals of ‘capacity’ albeit in a cross-jurisdictional way, and how this might impact on advocacy services. All these issues, especially the last one, are essential for improving the quality of life of people currently living with dementia.

A focus on the future, for example genetic analysis informing upon potential lifestyle changes one might have to prevent getting dementia at all, can be dispiriting for those currently living with dementia, who must not be led to feel ignored amongst a sea of savage cuts in social care. The realistic question for the next government, after May 7th 2015, of whatever flavour, is to how to catalyse change towards an integrated or ‘whole person’ ethos; ‘social prescribing‘, for example, might be a way for genuine innovations to improve wellbeing for people with dementia, such as ‘sporting memories‘, to gain necessary traction.

Empowering the person living with dementia with more than the diagnosis is fundamental. It is now appreciated that living well with dementia requires time to take care over appreciating the beliefs, concerns and expectations of the person in relation to his or her own environment. This interplay between personhood and environment for living well with dementia has its firm foundations in the work of the late great Tom Kitwood, and has been assumed by the most unlikely of bedfellows in the form of ‘person centred care’ even by multinationals.

Rather late in the day, and this seemed to be a mutual collusion between corporate-acting charities and the media, as well as Pharma, was a volte face on misleading communications about the efficacy of medications used to treat dementia. NICE, although potentially themselves a target of ‘regulatory capture’, were unequivocal about their conclusions; that a class of drugs used to treat ideally early attentional and mnemonic problems in early dementia of the Alzheimer type, had a short-lived effect on symptoms. of a matter of a few months, and did nothing to slow progression of disease. Policy is obligated though to accommodate that army of people who have noticed substantial symptomatic benefits for that short period of time with such medications such as aricept (one of the medications known as cholinesterase inhibitors)? Notwithstanding that, I dare say a medication ‘to stop dementia in its tracks’, as has been achieved for some cancers and HIV/AIDS, would be ‘motivating’, though I think the parallels medically between the dementias, HIV/AIDS and cancer have been overegged by non-clinicians.

And this was after spending many years researching these medications. The opportunity cost of the NHS pursuing the medical model is not inconsiderable if one is indeed wishing to ‘count the cost’ of dementia, compared to what could have been achieved through simple promotion of living well methods.

Large charities across a number of jurisdictions have clearly been culprits, and are likely to be hoisted by their ptard, as organisations as the Dementia Alliance International, a group of leading people living with dementia, successfully reset the agenda in favour of their interests at the Puerto Rico Alzheimer’s Disease International Conference this year.

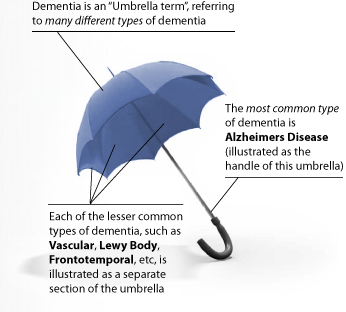

The second problem that still needs addressing is diagnosing the conditions which commonly come under “the dementia umbrella”.

[Source: here]

And clearly, the millions spent on Dementia Friends, a Department of Health initiative delivered by the Alzheimer’s Society, provides a basic core of information about dementia. It has a target of one million ‘dementia friends’, which looks unachievable by 2015 now. This figure was based on Japan, where the social care set-up is indeed much more impressive anyway, and which has a much lager population.

The messages of this campaign are pretty rudimentary, one quite ambiguous. The campaign suffers from training up potentially a lot of people with exactly the same information, delivered by people with no academic or practitioner qualifications in dementia necessarily. This means that such ‘dementia friend champions’ are not best placed to discuss at all the difference between the various medical presentations of dementia in real life, nor any of the possible management steps. Egon Ronay it is not, it is the Big Mac of dementia for the masses. But some would say it is better than nothing.

But has training up so many dementia friends actually done a jot about making the general public into activists for dementia, like being a bit more patient with someone with dementia in a supermarket queue? Dementia Friends clearly cannot address how a member of the general public might ‘recognise’ a person with dementia in the community, let alone be friendly to them, just by mere superficial observation of their behaviour. It is actually impossible to do so – laying to the bed the completely misleading notion that schoolchildren have been able to recognise the hallmarks of dementia in their elders, which have been missed by their local GPs.

This first issue about shifting attitudes in perception and identity of dementia is very much linked to the issue of diagnostic rates. A public accounts committee report in January 2008 had revealed that two-thirds of people with dementia never receive a specialist diagnosis. Only 31% of GPs surveyed by the NAO agreed that they had received sufficient training to help them diagnose and manage dementia, and doctors have less confidence about diagnosing the disease in 2007 than they had in 2004.

Have things fundamentally changed in this time? One suspects fundamentally not, as there has always been a reluctance to do anything more than a broad brush public health approach to the issue of diagnosis.

Goodhart’s law is named after the banker who originated it, Charles Goodhart. Its most popular formulation is: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” The original formulation by Goodhart, a former advisor to the Bank of England and Emeritus Professor at the London School of Economics, is this: “As soon as the government attempts to regulate any particular set of financial assets, these become unreliable as indicators of economic trends.”

And now it turns out that recoding strategies are being developed in primary care so as possibly to inflate the diagnostic rates artifactually. But while the situation arises that people in the general public may delay seeing their GP, and thereafter by mutual agreement the GP and NHS patient decide not to go on further ‘tests’, primary care can quite easily sit on many people receiving a diagnosis. The evidence base for mechanisms such as ‘the dementia prevalence calculator’ has been embarrassingly thin.

For example, Gill Phillips gives a fairly typical description of someone ‘worried well’ over functional problems at a petrol pump very recently, but the acid test for English policy is whether a person such as Phillips would feel inclined at all to see a Doctor over her ‘complaints’? The danger with equating memory problems with dementia, for example, means that normal ageing, while associated with dementia, can all too easily become medicalised.

And while there are possibly substantial disadvantages in receiving a diagnosis, both personally (e.g. with friends), professionally (e.g. employment), or both (e.g. driving licence), one should consider the limitations of national policy in turning around deep-seated prejudice, stigma and discrimination. And the solution to loneliness, undoubtedly a profound problem, is not necessarily becoming a ‘Dementia Friend’ if this means in reality getting the badge but never befriending a person with dementia? A ‘point of action’ like donating to a large corporate charity may be low hanging fruit for members of the public and large charities, but I feel English policy should be ambitious enough to consider shifting deep-rooted problems.

Such problems would undoubtedly be mitigated against if any Government simply came clean about what has been the increase in resource allocation, if any, for specialist diagnostic and post-diagnostic support services following this drive for improved dementia diagnosis rates. Lack of counselling around the period of diagnosis, with some people being reported as just being recipients of an ‘information pack’, is clearly not on, as a diagnosis of dementia, especially (some would say) if incorrect, is a ‘life changing event’.

Too often people with dementia, and close friends or family, describe only coming into contact with medical and care services at the beginning and end of their experience of a dementia timeline. Different symptoms, and different medications to avoid, are to be expected depending on which of the hundred causes of dementia a person has; for example Terry Pratchett and Norman McNamara have two very different types of dementia, posterior cortical atrophy and diffuse Lewy Body disease respectively. There is going to be no ‘quick fix’ for the lack of specialist support, though there is undoubtedly a rôle for ‘drop in‘ centres to provide a non-threatening environment for the discussion of dementia, encouraging community networks.

Ultimately, the diagnosis of dementia should be right for the person, at the correct time for him or her. This is the philosophy behind ‘timely’ rather than ‘early’ diagnosis, a battle which certain policy-makers appear to have won at last. Empowering the person living with dementia with that diagnosis can only be done on that personal level, with proper time and patience; ensuring sustainable dignity and respect for that person with a possible life-changing diagnosis of dementia.

The third priority of the strategy inevitably will be to improve the quality of care and support for people once they have been diagnosed.

At one end, it would be enormously helpful if the clinical regulators could hone on their minimum standard of care and those people responsible for care, including management. This is likely to be done in a number of ways, for example through wilful neglect, or the proposed anticipated proposals from the English Law Commission on the regulation of healthcare professionals anticipated to be implemented – if at all – in the next Government.

At the other end, there has been a powerful realisation that the entire system would collapse if you simply factored out the millions of unpaid family caregivers. They often, despite working extremely hard, report being nervous about whether their care is as good as it should be, and often do not consider themselves ‘carers’ at all.

There have clearly been issues which have been kicked into the long grass, such as tentative plans for a National Care Service while such vigorous energy was put into the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge. “Dementia friendly communities”, while an effective marketing mantra, clearly needs considerably more clarification in detail by policy makers, or else it is at real danger of being tokenistic patronisingly further stereotypes. Nobody for example would dare to suggest a policy framework called “Black friendly communities”. Whilst there are thousands of specialist Macmillan nurses for cancer, there’s about a hundred specialist Admiral nurses for dementia.

We clearly need more specialist nurses, even there is some sort of debate lurking as to whether Admiral nurses are ‘the best business model’. However, the naysayers need to tackle head on how very many people, such as those attending the Alzheimer’s Show this weekend in Olympia, describe a system ‘on its knees’, with no real proper coordination or guidance for people with dementia, their closest friends and families, to navigate around the maze of the housing, education, financial/benefits, legal, NHS and social care systems.

A rôle for ‘care coordinators‘ – sometime soon – will have to be revisited one suspects. But it is clearly impossible to have this debate without a commitment from government to put resources into a adequate and safe care, but while concerns about ‘efficiency savings’ and staffing exist, as well as existing employment practices such as zero-hour contracts and paid carers being paid below the minimum wage, how society values carers will continue to be an issue.

At the end of the day, care is profoundly personal, and repeatedly good care is reported by people who have witnessed continuity of care (away from the philosophy of the delivery of care in 15-minute “bite size chunks”). Unfortunately, the narrative in the NHS latterly has become one of business continuity, rather than clinical professional continuity, but this should ideally be factored into the new renewed strategy as well. I feel that this renewed strategy will have to accommodate actual findings from the literature taken as a whole, which is progressing at a formidable rate.

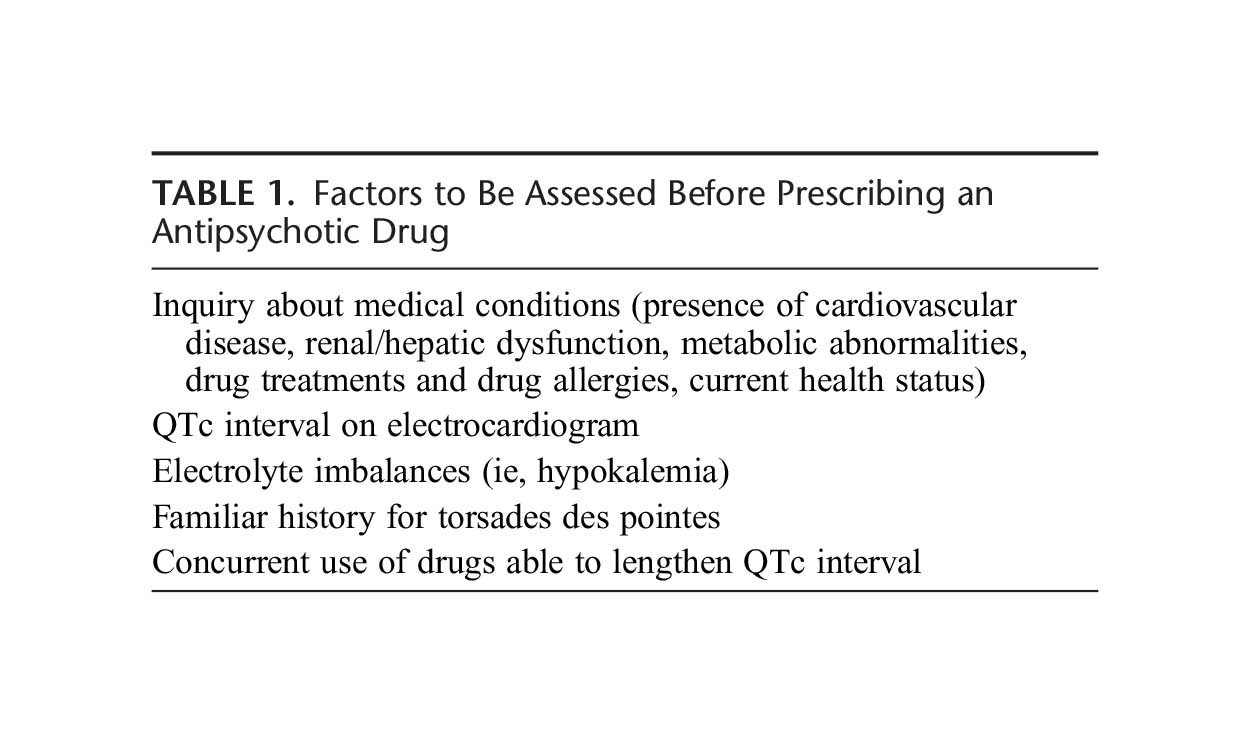

In a paper from February 2014, the authors review the the safety of the use of antipsychotics in elderly patients affected with dementia, restricting their analysis mainly to the last ten years. They concluded, “Use of antipsychotics in dementia needs a careful case-by-case assessment, together with the possible drug-drug, drug-disease, and drug-food interactions.” But interestingly they also say, “Treatment of behavioral disorders in dementia should initially consider no pharmacological means. Should this (sic) kind of approach be unsuccessful, medical doctors have to start drug treatment. Notwithstanding controversial data, antipsychotics are probably the best option for short-term treatment (6-12 weeks) of severe, persistent, and resistant aggression.” There are very clearly regulatory concerns of the safety of some antipsychotics, and yet the consensus appears to be they – whilst carrying substantial risk in some of very severe adverse effects – may also be of some benefit in some. It will be essential for the new National Dementia Strategy keeps up the only rapidly changing literature in this area, as do the clinical regulators.

Finally, in summary, I believe that there is enormous potential for England, and its workforce, to lead the way in dementia, in a way of interest to the rest of the world. I do think it needs to take account of the successes and problems with the five year strategy just coming to an end, with a three-pronged attack particularly on perception and identity, diagnosis and care. But, unsurprisingly, I believe that there are still a few gear-changes to be made culturally in the NHS, however it becomes delivered in the near future. There needs to be a clear idea of the needs of all stakeholders, of which the needs of persons with dementia, and those closest to them, must come top. There needs to be clear mechanisms for disseminating good practice, and leading on evidence-based developments in dementia wherever they come from in the world. And dementia policy should not be divorced from substantial developments from other areas of NHS England’s strategic mission: particularly in long-term conditions, and end-of-life care. This, again, would be the NHS delivering the right level of help for all those touched by dementia, from the point of diagnosis and well beyond.

Despite the sheer enormity of the task, I am actually quietly confident.

A timely reminder from Prof Sube Banerjee, co-author of ‘Living well with dementia’ (2009)

Apart from one caption saying ‘suffer from dementia’, this video I thought was excellent.

Sube gives a very clear definition of dementia which I really liked.

I think the point that dementia is not a part of ageing, but associated with ageing, is extremely important. I think we’re likely to have increasing concern that dementia can be difficult to diagnose in certain communities. For example, in some Asian communities, there is not even a word for ‘dementia’.

Missing from Sube’s account is the fact we can do something for people living with dementia, which is why I actively promote ‘living well with dementia’.

‘Living well with dementia’ might seem at first glance like a bit of a crap slogan, and actually quite offensive for those people who have witnessed loved ones in severe forms of dementia. But it’s an attempt to convey the idea that every individual with dementia is entitled to respect and dignity, and there is much we can do to enable people to live well with dementia by a careful study of the person and his or her environment.

It is apart from anything else the name of the 2009 English strategy, which Sube co-wrote, and which is about to be renewed.

This video is of course particularly timely for ‘Dementia Awareness Week’ running from May 18-24 2014. Our Facebook page is here.

“The Alzheimer’s Show” tomorrow and Saturday: my competition

I’m going to the Alzheimer’s Show tomorrow and on Saturday (Friday 15th May and Saturday 16th May 2014) in London Olympia. I am looking forward to seeing and chatting with many of my friends there.

I quite like the approach of the show as it is accessible to people with dementia as well as people who help to support people living with dementia.

The show’s official flier can be downloaded off their official website.

There’ll be over exhibitors including care at home, care homes, living aids, funding, legal advice, respite care, complementary therapies, training, telecare, assistive technology, charity, research, education, finance and entertainment.

You’ll get a chance to be a “Dementia Friend“.

I have written about the five key messages of “Dementia Friends”, as my PhD was successfully awarded in the cognitive neuropsychology of dementia at the University of Cambridge.

My slot – “Meet the author”

I’m thrilled to be doing a half an hour slot called ‘Meet the author': details here.

My book is called “Living well with dementia”. It also happens to be the name of the current five-year English dementia policy, about to be renewed.

(@mrdarrengormley and I)

I was especially honoured to receive this book review from the prestigious ‘Nursing Times‘.

I feel very strongly that living well with dementia must be a critical plank in the renewed English dementia policy, whichever party/parties come to power on May 8th 2015.

As I explained in my short article in the “ETHOS” journal, living well with dementia is perfectly understandable in the context of integrated care or whole person care.

There’s no doubt that values-based commissioning, promoting wellbeing in dementia, should be a core feature of English health policy in the near future. I discuss one application here in the Health Services Journal recently.

My competition

To be eligible you will need to be at the Alzheimer’s Show on one of the two days to pick up your prize.

Required:

Simply respond to the following –

You must tweet this by the day on which you intend to be at the Alzheimer’s Show.

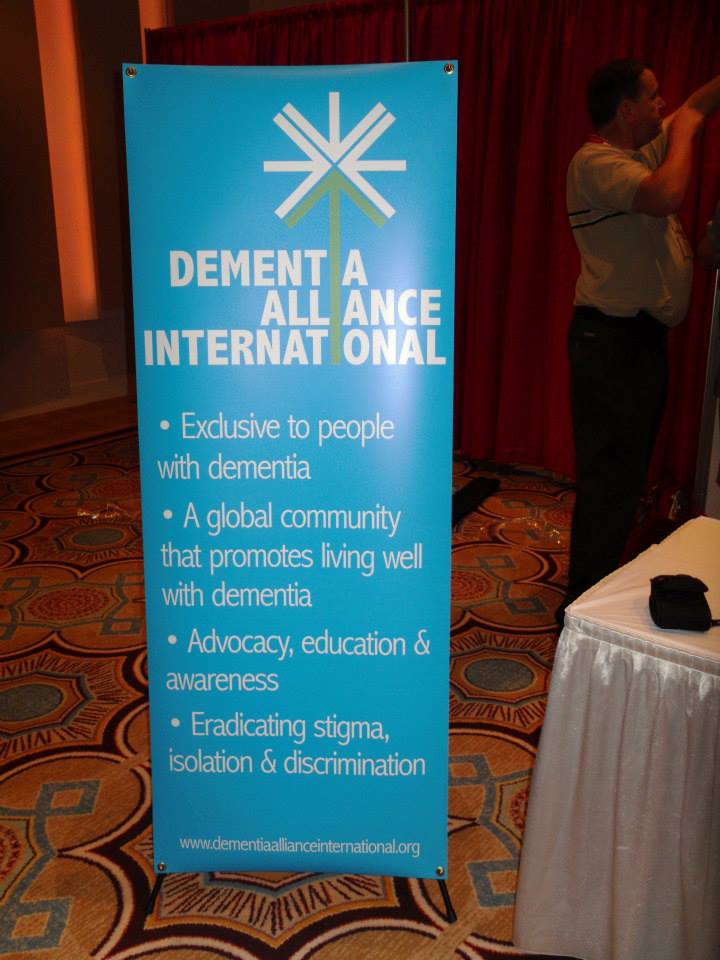

Really proud of my friends living well with dementia at #ADI2014 Puerto Rico

29th International Conference of Alzheimer’s Disease International

Dementia: Working Together for a Global Solution

1-4 May 2014, San Juan, Puerto Rico

ADI and Asociacion de Alzheimer y Desordenes Relacionados de Puerto Rico invite representatives from around the world, from medical professionals and researchers to people with dementia and carers, all with a common interest in dementia.

The conference programme – details given on this website – has streams including research, advocacy and care.

I am particularly proud of my close friend, Kate Swaffer (@KateSwaffer).

Kate is in a volunteer advocacy position, also working as a consumer on the National Advisory Consumers Committee, and the Consumer’s Dementia Research Network.

She contributes so much value to the people who are lucky to know her.

Kate lives in Adelaide, Australia. She loves cats like me. She has a formidable interest and experience in many things such as academia, media, clinical quality, and cuisine. She happens to live with first-hand experience of living with a dementia, and is a sheer joy to learn off.

Dementia Alliance International is a non-profit group of people with dementia from the USA, Canada, Australia and other countries that seek to represent, support, and educate others living with the disease, and an organization that will provide a unified voice of strength, advocacy and support in the fight for individual autonomy and improved quality of life.

Their membership is open to anyone with any type of dementia. Click here to inquire about membership.

PHOTOS ALL BY KATE SWAFFER APART FROM THE ONES WITH KATE IN THEM

Kate sporting a very important message for those of us who are passionate about a person-centred approach promoting living well with dementia.

This philosophy does not give undue priority to a medical model which pushes drugs which currently have very modest effects, or certain vested interests.

Living well with dementia in the English jurisdiction is a policy plank I’ve extensively reviewed for the English jurisdiction here.

A wonderful picture of Kate and Gill (@WhoseShoes). I am very proud of them having made this global journey to Puerto Rico.

And here’s Gill encouraging full participation!

The review of my book “Living well with dementia” today in Nursing Times

Thanks very much to the team at @NursingTimes for the first review of my book “Living well with dementia”.

I am hugely honoured.

This review was first posted on the page http://www.nursingtimes.net/opinion/book-club/living-well-with-dementia/5070460.blog?blocktitle=Nursing-Book-club&contentID=8080 in the “Book club” series of the magazine.

Title: Living Well with Dementia

Author: Shibley Rahman

Publisher: Radcliffe Publishing

Reviewer: Nigel Jopson, home manager, Birdscroft Nursing Home, Ashtead, Surrey

What was it like?

A meaty 300 plus pages book that attempt to cover all aspects of the dementia experience and it succeeds. It looks at the concept of living well what it is, how to measure it and how to develop services and attitudes to incorporate it. The book is up to date and relevant and has excellent sources and references. There are parts that can act as an instruction manual for good practice such as the suggestions about dealing with consent in chapter 11. A definite “cut out and keep” piece. Probably the most useful book I have read this year.

What were the highlights?

It covers everything you are likely to encounter in an accessible and informative way. It is nice to see some comments on ward design rather than purely care home as is more common.

My favourite part was in the conclusion where the author says “…writing a book on wellbeing in dementia is an impossible task.” I believe that may be the only part where she is wrong as this book is fabulous.

Strengths & weaknesses:

An enormous amount of information presented well and user friendly. I was worried it may have been too academic but it was not. It has good references and I particularly liked the way it attempted to integrate the whole idea and encouraged the use of other sources.

Who should read it?

This book should be essential reading for anybody with any contact with people living with dementia, which realistically I suppose means everybody. It can help towards a better understanding not only of dementia but the ways that peoples’ lives can be improved and enriched with a little effort and knowledge.

A person newly diagnosed with dementia has a question for primary care, and primary care should know the answer

Picture this.

It’s a busy GP morning surgery in London.

A patient in his 50s, newly diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, a condition which causes a progressive decline in structure and function of the brain, has a simple question off his GP.

“Now that I know that I have Alzheimer’s disease, how best can I look after my condition?”

A change in emphasis of the NHS towards proactive care is now long overdue.

At this point, the patient, in a busy office job in Clapham, has some worsening problems with his short term memory, but has no other outward features of his disease.

His social interactions are otherwise normal.

A GP thus far might have been tempted to reach for her prescription pad.

A small slug of donepezil – to be prescribed by someone – after all might produce some benefit in memory and attention in the short term, but the GP warns her patient that the drug will not ultimately slow down progression consistent with NICE guidelines.

It’s clear to me that primary care must have a decent answer to this common question.

Living well is a philosophy of life. It is not achieved through the magic bullet of a pill.

This means that that the GP’s patient, while the dementia may not have advanced much in the years to come, can know what adaptations or assistive technologies might be available.

A GP will have to be confident in her knowledge of the dementias. This is an operational issue for NHS England to sort out.

He might become aware of how his own house can best be designed. Disorientation, due to problems in spatial memory and/or attention, can be a prominent feature of early Alzheimer’s disease. So there are positive things a person with dementia might be able to do, say regarding signage, in his own home.

This might be further reflected in the environment of any hospital setting which the patient may later encounter.

Training for the current GP is likely to differ somewhat from the training of the GP in future.

I think the compulsory stints in hospital will have to go to make way for training that reflects a GP being able to identify the needs of the person newly diagnosed with dementia in the community.

People will need to receive a more holistic level of support, with all their physical, mental and social needs taken into account, rather than being treated separately for each condition.

Therefore the patient becomes a person – not a collection of medical problem lists to be treated with different drugs.

Instead of people being pushed from pillar to post within the system, repeating information and investigations countless times, services will need to be much better organised around the beliefs, concerns, expectations or needs of the person.

There are operational ways of doing this. A great way to do this would be to appoint a named professional to coordinate their care and same day telephone consultations if needed. Political parties may differ on how they might deliver this, but the idea – and it is a very powerful one – is substantially the same.

One can easily appreciate that people want to set goals for their care and to be supported to understand the care proposed for them.

But think about that GP’s patient newly diagnosed with dementia.

It turns out he wants to focus on keeping well and maintaining his own particular independence and dignity.

He wants to stay close to his families and friends.

He wants to play an active part in his community.

Even if a person is diagnosed with exactly the same condition or disability as someone else, what that means for those two people can be very different.

Once you’ve met one person with dementia, you’ve done exactly that: you happen to have met one person with dementia.

Care and support plans should truly reflect the full range of individuals’ needs and goals, bringing together the knowledge and expertise of both the professional and the person. It’s going to be, further, important to be aware of those individuals’ relationships with the rest of the community and society. People are always stronger together.

And technology should’t be necessarily feared.

Hopefully a future NHS which is comprehensive, universal and free at the point of need will be able to cope, especially as technology gets more sophisticated, and cheaper.

Improvements in information and technology could support people to take control their own care, providing people with easier access to their own medical information, online booking of appointments and ordering repeat prescriptions.

That GP could herself be supported to enable this, working with other services including district nurses and other community nurses.

And note that this person with dementia is not particularly old.

The ability of the GP to be able to answer that question on how best her patient can lead his life cannot be a reflection of the so-called ‘burden’ of older people on society.

Times are definitely changing.

Primary care is undergoing a silent transformation allowing people to live well with dementia.

And note one thing.

I never told you once which party the patient voted for, and who is currently in Government at the time of this scenario.

Bring it on, I say.

Public engagement with science must be two-way: that’s why persons with early dementia are so important

I spent some of this afternoon at the Wellcome Trust on Euston Road. Euston Road is of course home of the oldest profession, as well as the General Medical Council too.

I was invited to go there to discuss my plans to bring about a behavioural change in dementia-friendly communities. You see, for people with early dementia, say perhaps people with newly diagnosed dementia and full legal capacity, I feel we should be talking about communities led by people with early dementia.

The last few years for me as a person with two long term conditions, including physical disability, have really given me an urge to speak out on behalf of people who can become too easily trapped by being ‘medicalised’.

I have had endless reports of persons with dementia who have received no details about their dementia from the medical profession on initial diagnosis, and at worst simply given an information pack.

This is not good enough.

How we all make decisions is a fundamental part of life. When a person loses the ability to make decisions, it can be a defining moment – loss of capacity triggers certain legal pathways. Whilst the state of the law on capacity is quite good (through the Mental Capacity Act 2005), it is likely that further welcome refinements in the law on capacity will be seen through the current consultation on the said act.

I have been thinking about applying for a big grant to fund activities in allowing a discussion of decision-making in people with early diagnosis, the science of decisions, and what one might do to influence your decision-making (such as not following the herd).

I’ve also felt that quite substantial amounts of money get pumped into Ivory Tower laboratories on decision-making, but scientists would benefit from learning from people with early dementia regarding what they should research next, as much as informing people with early dementia what the latest findings in decisions neuroscience are.

Also, the medical profession and others are notoriously bad at asking people with dementia what they think about their own decision making. This ‘self reflection’ literature is woefully small, and this gap I feel should be remedied.

I simply don’t think that what scientific funding bodies do has necessarily to interfere with the NHS. I think a motivation to explain and discuss the science of decisions to stimulate a public debate is separable from what the NHS does to encourage people to live well with dementia. This debate can not influence what scientists do, but can influence what lawyers and parliament wish to do about capacity in dementia.

Persons can be encouraged to live well with dementia, and when they become ill they become patients of the NHS. Living well with dementia is for me a philosophy, not a healthcare target. If I can do something to promote my philosophy and help people, I will have achieved where many people in their traditional rôles as medical doctors have gloriously failed as regards dementia.

Why I’m on a mission to explain the science of decisions to people living with mild dementia

As a person who is physically disabled, and who has a speech impediment due to a meningitis from 2007, I am more than aware of how people can talk down to you in a patronising way.

It’s why I am very sensitive about language: for example, even with the best intentions in the world, “dementia friendly communities” conjures up an intense feeling of ‘them against us’.

It’s really important to not do anything which can cause a detriment to any group of people.

If you happen to be living with a condition which could cause you to have difficulties, this is especially important.

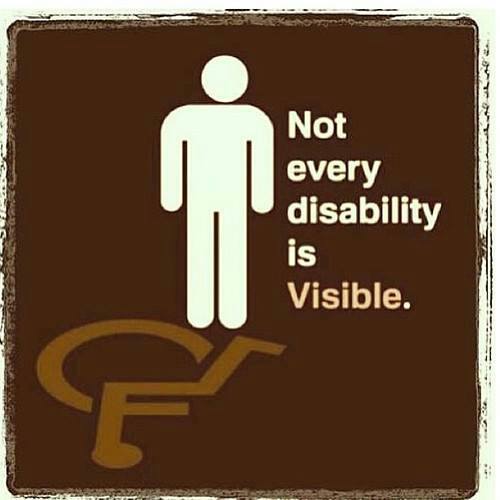

A “dementia” might be a disability under the Equality Act, and the person you’re speaking to might not obviously to you be living with a disability – it’s a ‘so-called invisibility’.

But – I’m deadly serious this. People shouldn’t be judged on what they can’t do. We all have failings of some sort. People should be encouraged for what they can do whenever possible. I don’t, likewise, consider the need for policy to embark on ‘non-pharmacological interventions’ as if what I’m talking about is second fiddle: living well with dementia is a complete philosophy for me.

In any other disability, you’d make reasonable adjustments. I see the need to explain how decisions are made to people with dementia as absolutely no different, both under the Equality Act (2010) and morally for a socially justice-oriented nation.

The excitement about how ‘decisions’ are made was recently described in the book by Prof Daniel Kahneman, “Thinking fast and slow”.

How we hold information for long enough to weigh up the pros and cons fascinates me.

Kahnemann, and others, feel that there are two systems.

System 1 is fast; it’s intuitive, associative, metaphorical, automatic, impressionistic, and it can’t be switched off. Its operations involve no sense of intentional control, but it’s the “secret author of many of the choices and judgments you make”. System 2, on the other hand, is slow, deliberate, effortful. Its operations require attention. (To set it going now, ask yourself the question “What is 13 x 27?”

Kahneman is a hero of mine as in 2002 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for economics, but he is essentially a cognitive psychologist.

In 2001, I was awarded a PhD from Cambridge for my thesis in decision-making in frontal dementia. I was the first person in the world to demonstrate on a task of decision-making that people with frontal dementia are prone to make risky decisions, despite having very high scores on standard neuropsychological tests and having full legal capacity.

Now, one coma later following my meningitis, I have done my postgraduate studies in law, and I have become fascinated by the rather arbitrary way in which our law has developed the notion of mental capacity, based on our ability to make decisions.

People with dementia can lose their ability to make decisions, so decision-making is a fundamental part of their life. As neuroscience and law straddle my life, I should like to make it my personal mission to explain the science of decision-making to people with full capacity, and who happen to have a diagnosis of dementia.

I am all in favour of a world sympathetic to the needs of people living with dementia, but this requires from us as a society much greater literacy in what the symptoms and signs of dementia are. I am not convinced we’re anywhere near that.

In the meantime, I think we can aim to put some other people in the driving seat, and they rarely get put in the driving seat: yes, that’s right, it’s time to engage people with mild dementia in the scientific debate about how decisions are made.