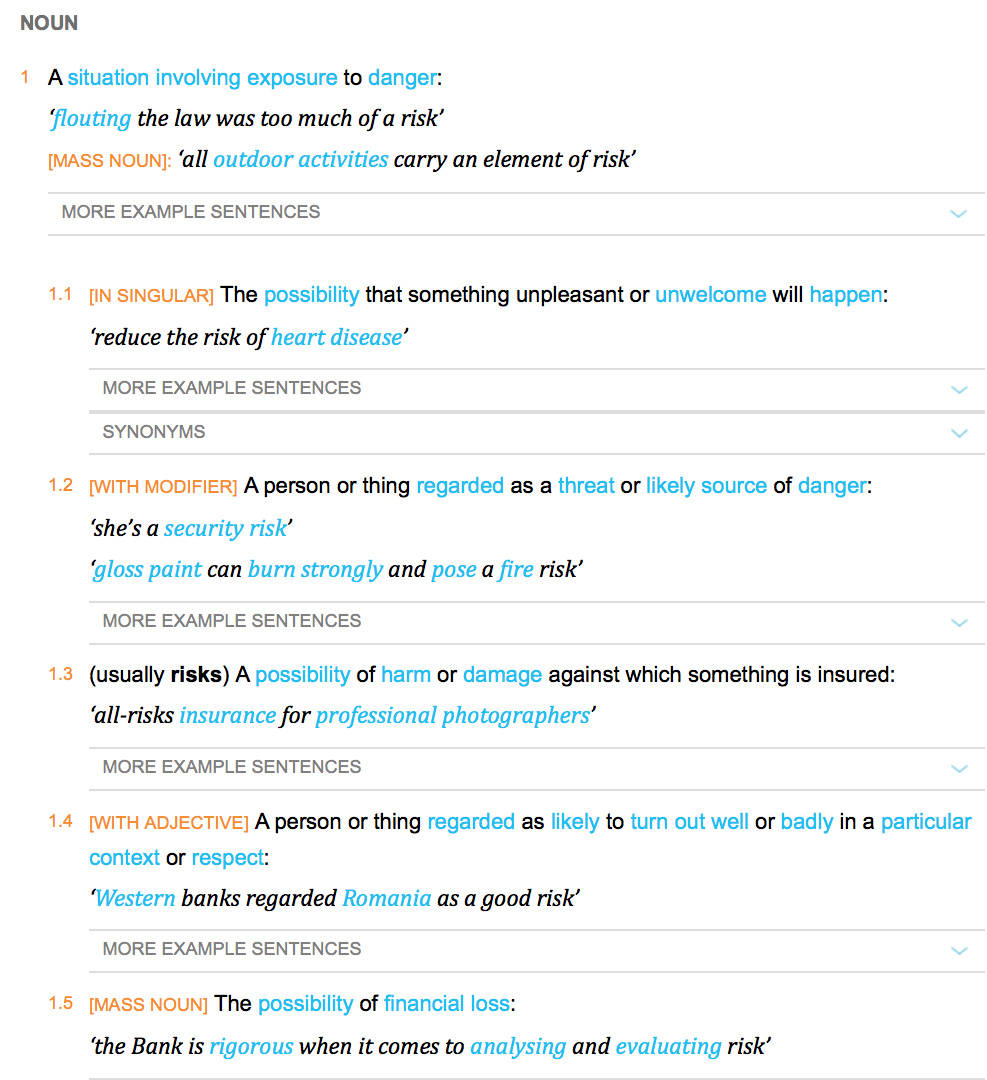

“Risk” is one of those entities which bridges the financial world with law and regulation, psychology or neuroscience. The simplicity of the definition of it in the Oxford English Dictionary rather belies its complexity?

It was a pivotal part of my own Ph.D. in the early diagnosis of the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia, awarded by the University of Cambridge in 2001. I was one of the very first researchers in the world to identify that ‘risk seeking behaviour’ is a key part of the presentation of many of these individuals, against a background of quite normal other psychological abilities and investigations including brain neuroimaging scans.

‘You need to break eggs to make an omelette’ is one formulation of the notion that you have to be able to make mistakes to achieve an overall goal. That particular sentence is, for example, used to convey the way in which you might have to put up with ninety nine turkeys before striking gold with one truly innovative idea. ‘Nothing ventured nothing gained’ is another slant of a similar idea. Interestingly, this phrase is often attributed to Benjamin Franklin. Franklin has an established reputation of his own as a ‘conceptual innovator‘.

It’s also a very interesting policy document on risk in dementia from the UK Department of Health, from 10 November 2010, a really useful contribution. This guidance was commissioned on behalf of the Department of Health by Claire Goodchild, National Programme Manager (Implementation), National Dementia Strategy. The guidance was researched and compiled by Professor Jill Manthorpe and Jo Moriarty, of the Social Care Workforce Research Unit, King’s College London.

Prof Alistair Burns, England’s clinical lead for dementia, has written a very focused and relevant Foreword to this piece of work. Here Alistair is, pictured with me earlier this week at the Dementia Action Alliance Annual Conference hosted in Westminster, London (“DAA Conference”). The event was a positive celebration of the #DAACC2A, “Dementia Action Alliance Carers’ Call to Action”, which embodies a movement where, “carers are acknowledged and respected as essential partners in care, and are supported with easy access to the information and the advice they need to assist them in carrying out their role.”

Risk enablement, or as it is sometimes known, positive risk management, in dementia involves making decisions based on different types of knowledge. However, people living with dementia and caregivers, quite often an eldest child or spouse, can handle risk in different ways. I feel that understanding living well with dementia is only possible through understanding the background to a person living with dementia, and his or her interaction with the environment. I’ve indeed written a comprehensive book on it, and I am in the process of writing a second book on it, which brings under the spotlight many of the key stakeholders, I believe, who contribute to “dementia friendly communities”.

Risk enablement is based on the idea that the process of measuring risk involves balancing the positive benefits from taking risks against the negative effects of attempting to avoid risk altogether. For example, the report cites the example of the risk of getting lost if a person with dementia goes out unaccompanied needs to be set against the possible risks of boredom and frustration from remaining inside. There are clearly various components of risk which might affect a person living with dementia. Risk engagement therefore becomes a constructive process of risk mitigation, an idea highly familiar to the law and regulation through the pivotal thrust of ‘doctrine of proportionality‘, that legislation must be both necessary and proportionate.

Risk enablement, it is argued, goes far beyond the physical components of risk, such as the risk of falling over or of getting lost, to consider the psychosocial aspects of risk, such as the effects on wellbeing or self-identity if a person is unable to do something that is important to them, for example, making a cup of tea. Therefore, the report proposes that “risk enablement plans” could be drawn up which summarise the risks and benefits that have been identified, the likelihood that they will occur and their seriousness, or severity, and the actions to be taken by practitioners to promote risk enablement and to deal with adverse events should they occur. These plans need to be shared with the person with dementia and, where appropriate, with his or her carer or caregiver. Thus advancing the policy construct of ‘personalisation’ offering choice and control, risk assessment tools are envisaged by the authors to help support decision making, and should include information about a person with dementia’s strengths and of his or her views and understanding about risk. Risk could apply to making a cup of tea, or going for a walk. We know that people living with dementia handle risks in different ways. For some people, a person living with dementia excessively walking beyond a local jurisdiction might be a known problem. For all the different causes of dementia medically, and for all the different ways in which individuals react to a dementia at different stages of the condition, a person can live with dementia in a sharply distinctive way.

Risk therefore in a hugely meaningful and substantial way has moved away from the “safety first” circles? And it fundamentally will depend on how an unique person living with his or her dementia embraces the environment in reality.

The idea that you need risk to live well with dementia is brought into sharp focus here by Chris Roberts, a friend of mine, speaking at the DAA Conference. I have recently begun to take risks in a highly enjoyable game for my #ipad3, which Chris indeed introduced me to, called, “Real Racing 3″. Here, Chris also talks about the crass way in which he was originally told his diagnosis, and lack of information about his condition given at the time of diagnosis. Therefore, Chris, I feel, brings into sharp focus a number of problem areas, which hopefully Baroness Sally Greengross and colleagues will address in a new five year strategy for England for 2015-20.