We’ve all done it: preaching to the choir, or pushing on an open door.

Turn back the clock, and you can listen to a recording of a radio programme where Reginald Maudling, Enoch Powell, Michael Foot and Roy Jenkins profoundly disagree on policy.

The timeline is this. It is perceived that the next step of defining the English dementia strategy will be the ‘implementation plan’ for Dementia 2020.

I am told we can probably expect this plan to surface around January 2016.

It’s worth looking at the document ‘Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia 2020‘.

Indeed, clinical specialist nurses are mentioned on page 27 in the section on support after diagnosis. This is where my original discussion had in fact started, on a recent blogpost on the need to define what exactly we mean by ‘post diagnostic support’ [blogpost here].

I was advised recently that NICE guidelines are of limited value, as CCGs are free to ignore NICE guidelines and other evidence bases for dementia. There is no obligation for CCGs to contain any expertise in dementia, including from dementia specialists including people living with dementia. CCGs are statutory insurance bodies; it is good marketing, however, if GPs happen to be amongst the personnel of CCGs, it’s a “win win”.

I have been to meetings of policy where very senior people, who should remain nameless, say that there’s no point having a plethora of good clinical outcomes unless there is a clear business model for a “cost saving”.

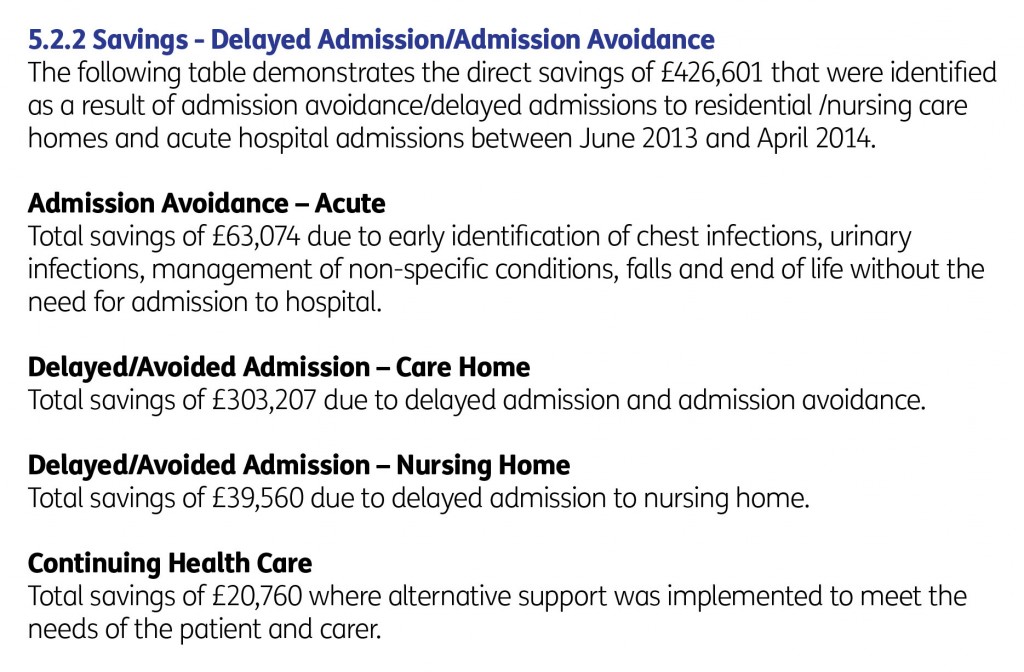

As it happens, numerous reports have emphasised the financial advantage of the Admiral nursing approach. The evaluation of the Norfolk Admiral Nurses programme showed a banquet of cost savings, including on avoidable admissions (p. 31).

Yes indeed as Beth Britton identifies here the central issue is ‘facing dementia and getting support’.

Some of the reasoning is as follows.

- The person with dementia must be seen as a unit, with a key friend or member(s) of family. This is the case from the very time the person is given a diagnosis.

- The Admiral nurse can advise this unit on the symptoms as they arise.

- The Admiral nurse network works in a variety of care settings, e.g. at home, in a residential setting, a hospital; this helps to ensure continuity of care.

- The Admiral nurse can, later on, guide the unit through palliative care issues.

- The Admiral nurse can make specialist referrals, such as if the medication needs adjustment, or some input is needed on a key aspect of ‘life planning’ (e.g. wills, power of attorney).

Two pivotal events might occur at some stage, for which an Admiral nurse can offer expertise: one when the person with dementia loses the legal ability to make decisions (‘capacity’), or when a person with dementia might choose to go into a residential setting – care home or nursing home.

Caring for people with dementia, as included in marriage vows as well, can be incredibly rewarding. However, caring is the equivalent of a full time job and the system is only kept afloat due to the millions of hours put in per year from unpaid carers (as well as carers, often made, on zero hour contracts and barely meeting the requirements for the national minimum wage). All of this is clinically significant as the wellbeing of the person with dementia is intimately related to the wellbeing of a carer (or ‘BUB’ as per Kate Swaffer‘s nomenclature).

The Admiral nurse can educate the unit, and other professionals, on what dementia is, and how a person with dementia can be best supported to live after the diagnosis.

I am sick of calling for a national dialogue, as national policy after national policy fails to make the argument for good clinical practice.

To be frank, I have become bored of looking for people to blame – apart from the fact that I feel that ‘clinical leaders’ in dementia have failed to lead on this crucial area of policy. I think dementia advisers and dementia support workers are wonderful, but you have to worry as they become overwhelmed in their rôle of signposting to ever dwindling services.

Some players in dementia are too tribal, actually putting their ‘tribal-ity’ ahead of the clinical needs of persons with dementia and carers. This is simply wrong.

I truly want all of this to be ‘in it together’. This means that we work and live together, all, for the benefit of people with dementia and carers. Due to stubborn political obstruction, the momentum for Admiral nurses simply is not there – compared to, for example, Marie Curie and Macmillan nurses – and the resources reflect this.

I sometimes think policy debate is somewhat contrived, and theatrical with everybody playing their expected part. I liken this orchestration to ‘The Truman Show‘.

Well, I have no wish to be a silent bystander to this grave error in policy, from the perspective of two professions. I think this political obstruction is getting in the way of fulfilment of s.1(1) Care Act – the promotion of wellbeing.

But I do think you do need to have discussions with people you profoundly disagree. For example, you might wish to have a discussion with Vladimir Putin over investment in our infrastructure, even if you disagree much with Russia’s human rights record.

Same for Modi.

Same for me and the people in charge of dementia policy.

The late Enoch Powell advises in this radio programme, above, that, only if you understand your opponent’s arguments properly can you understand why you are RIGHT and they are WRONG.

My summary. I think all persons living with dementia, and carers, deserve better.