One amazing phenomenon is that it’s possible to stimulate memories in people living with dementia by the presentation of football memorabilia, as described by Rachel Doeg here.

The transformation is quite remarkable: “reeling off expert knowledge and sharing collective memories that bring laughter and camaraderie to the group,and a boost to their self-esteem.”

“Bill’s story” is another brilliant example from “Sporting Memories“:

“Sporting memories” was established to explore the stimulation of living well in people with dementia, through conversations and reminiscence.

The Dementia Friends programme supports people who want better to understand all the implications of the condition. Last week saw celebrities and people living with dementia teaming up with the Dementia Friends Campaign to encourage even more of us to sign up. It is hoped that one million will be recruited by 2015.

One of the ‘talking points’ in ‘Dementia Friends’ might “the bookshelf analogy of Alzheimer’s Disease”.

This video taken from the “Dementia Partnerships” website shows Natalie Rodriguez, Dementia Friends Champion, using this analogy to describe how dementia may affect a person.

This simple explanation, orginally devised by Dr Gemma Jones, can be helpful for Dementia Friends Champions to explain dementia to others. A full description of it is given here.

The usual explanation of the early features of Alzheimer’s disease using the ‘bookcase analogy’

In this analogy, the brain has a number of ‘bookcases’ which store a number of memories, such as memory for events about the world, memory for sensory associations, or emotional memory, to name but a few.

Let’s now focus on the memory for events about the world bookcase.

The top shelves contain more recent memories, and, as you go down the bookshelf, more old memories are stored.

When you jog this memory shelf, the books on the top may wiggle a bit, causing minor forgetfulness about recent events, such as where you put your keys.

As you jog it a bit more, the books on the top shelf may fall off altogether, making it impossible to learn new stuff and retain stuff for a short period of time.

The bottom shelves of the short memory bookcase remain unperturbed.

The jogging of this memory for events about the world bookcase is equivalent to what happens in early Alzheimer’s disease, when something goes wrong in the top shelves only.

The top shelves correspond to the hippocampus part of the brain – it’s near the ear, and so called as it looks like a sea-horse. That’s where disease tends to happen first in Alzheimer’s disease.

So you can see what happens overall. In the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, a common cause of dementia, problems in short-term memory for events about the world can be profound, while long-term memories around the world are relatively infact.

As they correspond to different bookcases altogether, sensory and emotional memory are left relatively intact.

How the ‘bookcase analogy’ can be used to explain the phenomenon of “sporting memories”

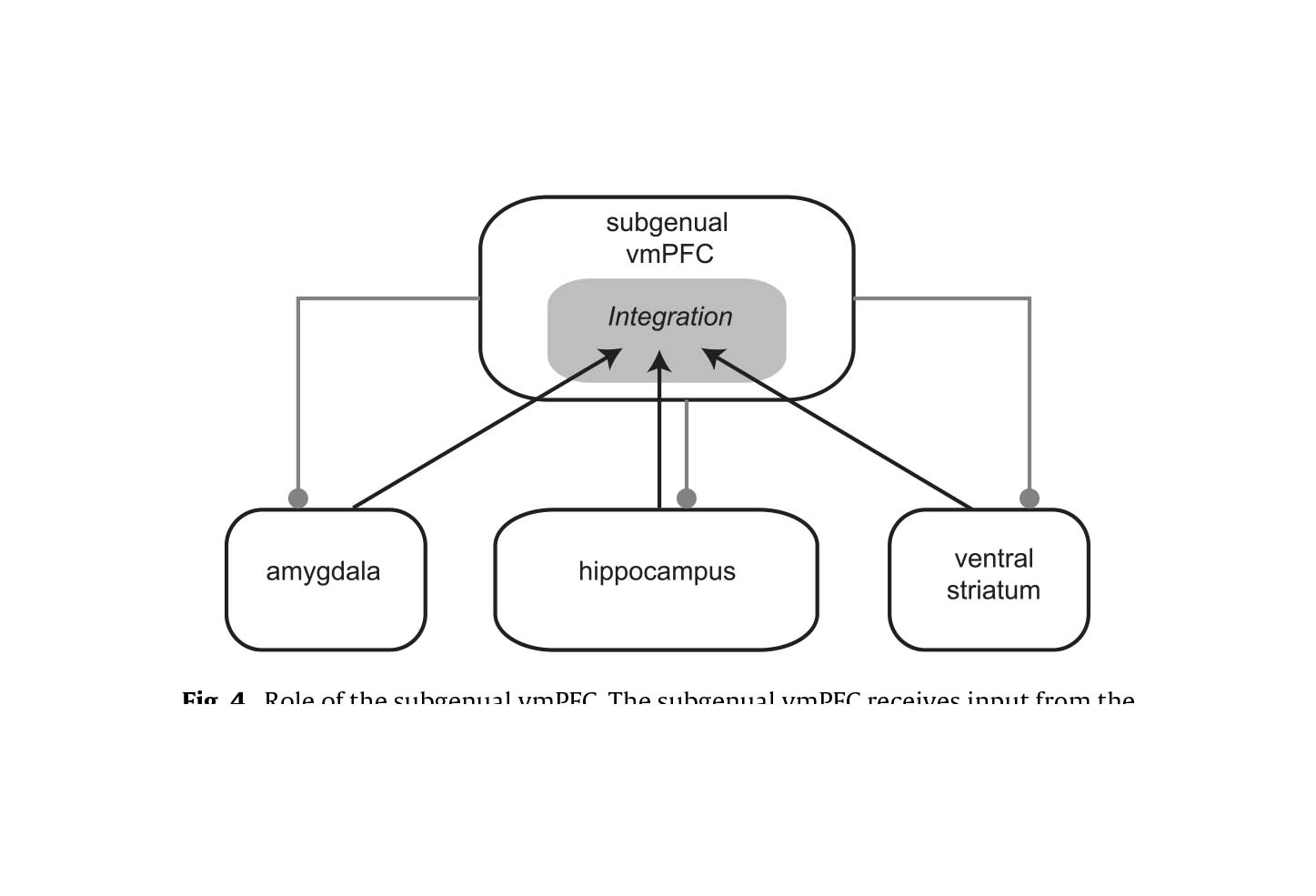

I haven’t mentioned another bookcase altogether. This is a memory of events about yourself – so-called “autobiographical memory” – and this is held in a part of the brain by the eye (the ventromedial subgenual cortex).

There’s a very good review from a major scientific journal, called “The role of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in memory consolidation” by Ingrid L.C. Nieuwenhuisa and Atsuko Takashima published recently in 2011.

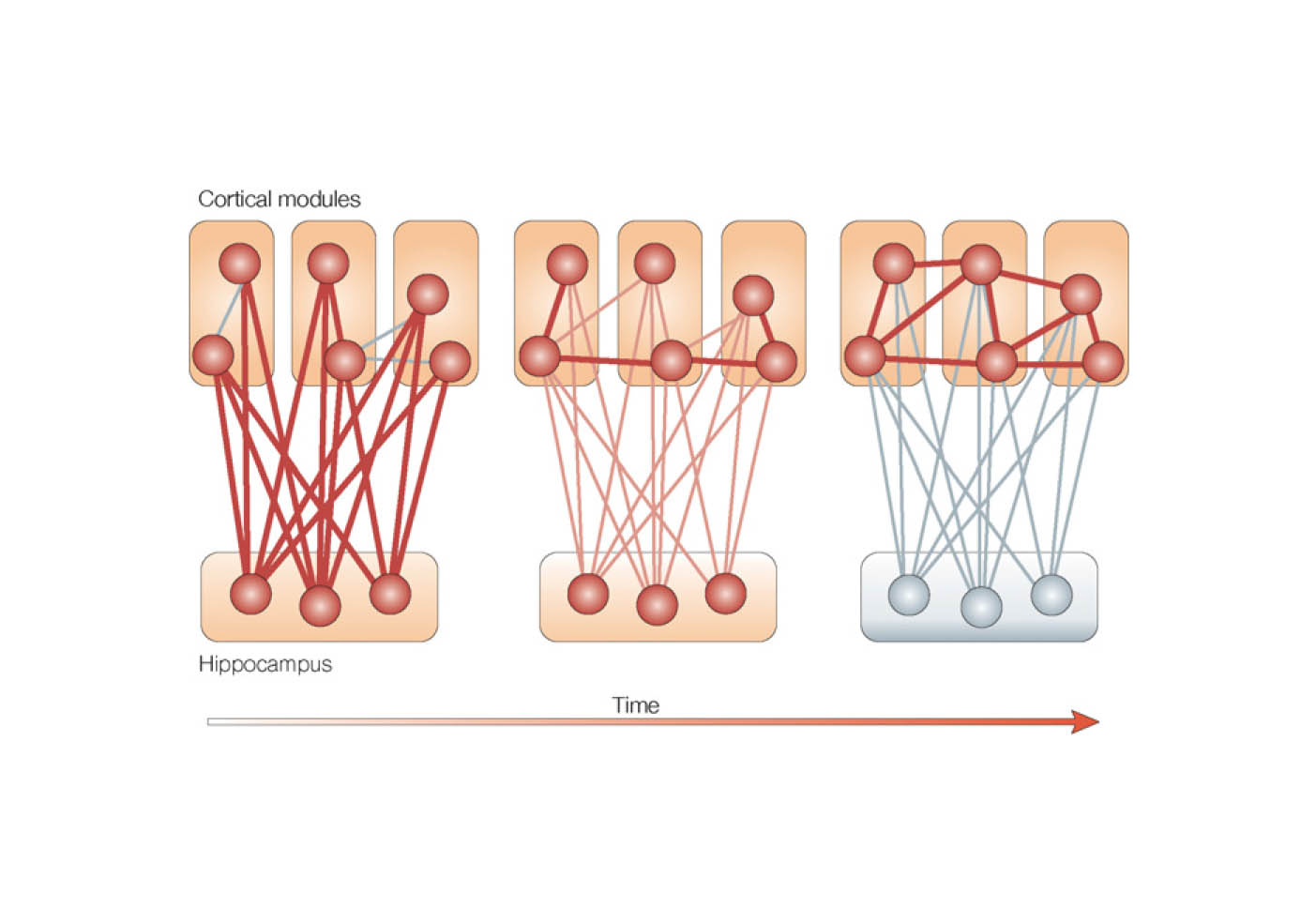

Autobiographical memories, such as sporting matches, are first formed in the hipppocampus, and they then get dispatched to a totally different part of the brain, the ventromedial/subgenual cortex as these memories become “consolidated”.

In other words, books can come from the events around the world bookcase, but while this is wobbling the autobiographical bookshelf is unscathed.

The crazy thing though is that the intact ventromedial prefrontal cortex is also connected with the intact amygdala in early Alzheimer’s disease, which means the autobiographical bookcase can arouse emotional memories in that bookshelf.

Sporting memories and “dementia friendly communities”

It is also a nominee under the category “National Initiative” in the Alzheimer’s Society first Dementia Friendly Awards, sponsored by Lloyds Banking Group and supported by The Telegraph, the winners of which will be announced on May 20. The awards recognise communities, organisations and individuals that have helped to make their area more dementia-friendly.

The awards shortlist is at alzheimers.org.uk/dementiafriendlyawards