The whole use of language surrounding the diagnosis of dementia matters, not least in the general context of how risk is communicated with the general public. A further problem is that medical terms often get adopted by more general media such as tabloids in a fairly non-discriminatory way. Take for example. the formal definition of an “epidemic” is:

“The occurrence in a community or region of cases of an illness, specific health- related behavior, or other health-related events clearly in excess of normal expectancy.”

(Greenland, Last and Porta, 2008)

According to Prof Paradis at Stanford University (2012), presented later by Paradis and colleagues (Paradis et al., 2012) in a public presentation, there has been an apparent ‘epidemic of epidemics‘, with no apparent restriction on the type of disease, on frequency or rates of affliction; there was no growth or contagion threshold. In the forthcoming decades, it is predicted that large numbers of people will enter the ages when the incidence rates of forms of dementia are the highest. People sixty years and over make up the most rapidly expanding segment of the population: in 2000, there were over 600 million persons aged 60 years or over worldwide, comprising just over 10% of the world population, and, by 2050 it is estimated that this figure will have tripled to nearly two billion older persons, comprising 22% of the world population (United Nations, 2007). Stephan and Blossom (2008) from the University of Cambridge state specifically that, “this ageing epidemic, while once limited to developed countries, is expected to become more marked in developing countries.” Supporting this, Sosa-Ortiz, Acosta-Castillo, and Prince (2012) propose that “global population aging has been one of the defining processes of the 20th century, with profound economic, political and social consequences. It is driving the current epidemic of dementia, both in terms of its extent and global distribution.” It could be that stakeholders in the research community, as Paradis (2011) proposes, are effectively competing for “social capital” (after Bourdieu, 1986). Bourdieu’s definition of ‘capital’ extends fat beyond the notion of material assets to capital that may be social, cultural or symbolic (Bourdieu 1986: cited in Navarro 2006).

In professional circles, the diagnosis of dementia enmeshes a plethora of ethical issues, as reviewed elegantly by Strech and colleagues (Strech et al., 2013):

- Risk of making a diagnosis too early or too late because of reasons related to differences in age- or gender-related disease frequencies

- Risk of making inappropriate diagnoses related to varying definitions of mild cognitive impairment

- Underestimation of the relatives’ experiences and assessments of the person with dementia

- Adequate point of making a diagnosis:

- Risk of disavowing signs of illness and disregarding advanced planning

- Respecting psychological burdens in breaking bad news

- Underestimation of the relatives’ experiences and assessments of the person with dementia Reasonableness of treatment indications:

- Overestimation of the effects of current pharmaceutical treatment options

- Considering challenges in balancing benefits and harms (side- effects)

- Not considering information from the patient’s relatives

- Adequate appreciation of the patient:

- Insufficient consideration of the patient as a person

- Insufficient consideration of existing preferences of the patient

- Problems concerning understanding and handling of patient autonomy

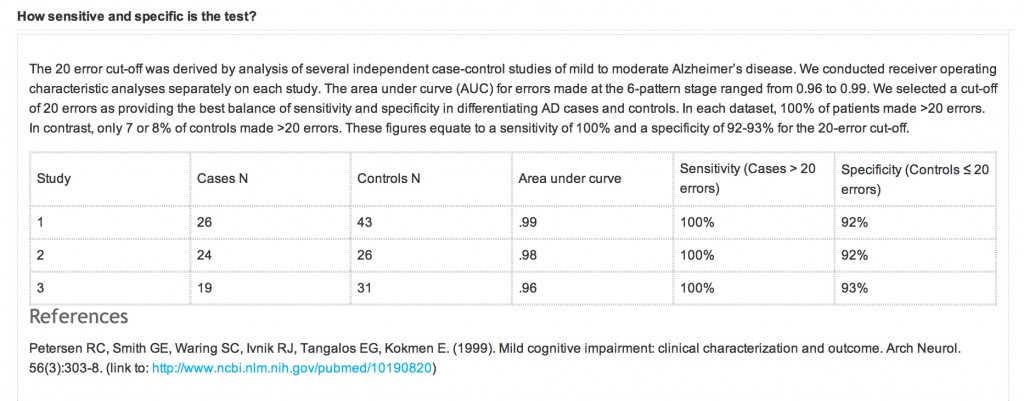

A correct early diagnosis may be clarifying, and appreciated by patients even without disease-modifying treatment, and a diagnosis could be valuable since it allows informed planning for the future (Kaduszkiewicz, Bachmann, and van den Bussche, 2008). A ‘positive test result’ indicating dementia of Alzheimer type (“DAT”) will almost certainly lead to extended follow-up., and that individual being plugged into the system. However, at worst, the diagnosis could lead to stigmatisation resulting in feelings of hopelessness, agony, and despair. The rôle of the clinician and support, such as family members, relatives, friends, and other members of the “dementia-friendly community”, will be to mitigate against this risk. From a legal perspective, a test result indicating DAT could potentially affect insurance premiums (sic), and the right for an individual to hold a driver’s licence, depending on the jurisdiction in question. Certainly, the ethical consequences in falsely diagnosed cases could be grave. Furthermore, as Matthson and colleagues explore (Matthson, Brax and Zetterberg, 2008), If a false positive diagnosis results in treatment, any harmful side effect is a serious infringe on the basic medical ethics principle of non-maleficience, accurately summarised in the Latin phrase primum non nocere (“first, do not harm”).

A salutory warning is provided by the well documented discussions of the communication of obesity as a public health issue. The very fast increase in mass media attention to obesity in the U.S. and beyond seems to have many of the elements of what social scientists call a ‘moral panic’. Moral panics are typical during times of rapid social change and involve an exaggeration or fabrication of risks, the use of disaster analogies, and the projection of societal anxieties onto a stigmatized group (Cohen, 1972; Goode and Ben-Yehuda, 1994). Moral panic is a term usually used to describe media presentation of something that has happened that the public will react to in a panicky manner. Moral panic has a tendency to exaggerate statistics and to create a ‘bogey-man’, known as a ‘folk-devil’ in sociological terms. In recent years moral panic and media presentation have covered a wide-ranging number of topics from HIV/AIDS in the 1980s to immigrants into the UK in the 2000’s. Moral panic goes back as far as World War One when the wartime government used the media to portray the Germans in a certain manner in the hope of provoking a response. The conduct of the media is pivotal in all this.

Despite arguably the very weak evidence that obesity represents a health crisis, scientific studies and news articles alike continue to treat the population’s weight gain as an “impending disaster”. A content analysis of 221 press articles discussing scientific studies of obesity found that over half employed alarming metaphors such as ‘time bomb’ (Saguy and Almeling, 2005). The fundamental problem is that there is no adequate treatment for the commonest type of dementia, DAT, and yet authors still talk in a language suggesting that it is possible to treat this epidemic successfully. For example, Korczyn and Vakhapova (2007) in their article entitled, “The prevention of the dementia epidemic”, cite polio as an example of an epidemic which was successfully ‘treated’.

“The last epidemic which has been fought with outstanding success is poliomyelitis. In order to win that war, the first step was to identify the cause, the polio virus. The next step, achieved within a few years, was to develop methods to cultivate the virus. Justifiably, J. Enders, T. H. Weller and F. C. Robbins were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1954 for this important discovery, which led to the development of immunization (sic) methods by A. B. Sabin and J. E. Salk.”

This is nothing new. Even the Department of Health (2002) has referred to the “obesity time bomb“:

“The growth of overweight and obesity in the population of our country – particularly amongst children – is a major concern. It is a health time bomb with the potential to explode over the next three decades…. Unless this time bomb is defused the consequences for the population’s health, the costs to the NHS and losses to the economy will be disastrous.” (Department of Health 2002)

In a remarkable paper, Bethan Evans (2010) considered the characterisation of obesity as a ‘threat to the future nation’ through considering obesity as a biopolitical problem – which simultaneously addresses the individual body and the ‘population’ (Foucault 1997) – and as a form of “pre-emptive politics”. According to Massumi (2007), pre-emptive action is not legitimised through ‘scientific truths’ established to know the future, but through the (re)production of ‘affective facts’ which make potential futures felt in the present. This ensures ‘any action taken to pre-empt a threat from emerging into a clear and present danger is legitimated by affective fact of fear, actual facts aside’ (Massumi 2007). An example of this use of language is seen in the report of Alzheimer’s Disease International (2012) on stigma in DAT. They clearly wish the reader to project to the future.

“Our healthcare and financial systems are not prepared for this epidemic. Dementia is the main cause of dependency in older people 1, and we will not have enough people to care for these large numbers of people with dementia. Globally, less than 1 in 4 people with dementia receive a formal diagnosis Without a diagnosis, few people receive appropriate care, treatment and support.”

The authors of that particular report cite numerous examples supporting their thesis than an early diagnosis is beneficial. For example, they state that, Scotland’s national dementia plan includes ‘overcoming the fear of dementia’ as one of its plan’s five key goals. This plan seeks to improve access to diagnosis by providing general practitioners with information and resources. If the “dementia epidemic” is a real one, according to Nepal and colleagues (Nepal et al., 2008), policy strategies to deal with the dementia “epidemic” could be informed in a number of ways. The prevalence depends upon interaction of age with other factors (e.g., co-morbidities, genetic or environmental factors) that in turn are subject to change. If onset of dementia could be postponed by modulating its risk factors, this could significantly affect its incidence (e.g. review, Treves and Korczyn, 2011). The need for longitudinal and population-based data that would enable analyses of resource allocation and cost implications has been identified (Wimo and Winblad, 2004). Conducting prospective intervention studies is an established approach to test alternative policy models in the field, but these studies require substantial investment in time and resources. Computer-based dynamic microsimulation models are an ideal alternative to these, as the computer simulations provide an opportunity to test a range of policy options in a virtual world in a shorter time frame.

Nonetheless, this debate is better ‘out than in’, and should be conducted openly for the benefit of those individuals with dementia, and their most immediate people in their community, including partners, friends, relatives or family members. Even charities have been known to use terms such as ‘epidemic’ and ‘timebomb’ in common parlance, and the debate above could go some way into explaining why the word “early” in dementia diagnosis has been replaced by “timely” in most UK circles. As we are all relatively new to the dementia journey, some more than others, it is appropriate we stop to think before rushing at full speed into an uncontrollable situation about communication.

[Thank you very much to @nchadborn and @peterdlrow for useful discussions on this issue through the medium of ‘Twitter’.]

References

Alzheimer’s Disease International (2012) World Alzheimer Report 2012: Overcoming the stigma of dementia, London: Alzheimer’s Disease International, available at: http://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2012.pdf.

Bourdieu, P. (1986) The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.) Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (New York, Greenwood), 241-258.

Cohen, Stanley. (1972) Folk Devils and Moral Panics, Routledge: New York.

Department of Health (2002) Annual report of the chief medical officer 2002: Health check, on the state of the public health, available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/en/PublicationsAndStatistics/Publications/AnnualReports/DH_4006432.

Evans, B. (2010) “Anticipating fatness: childhood, affect and the pre-emptive ‘war on obesity’”, Trans Inst Br Geogr, 35, pp. 21–38.

Foucault, M. (1997) “Society must be defended: lectures at the Collège de France 1975–76 Translated by Macey, D.”, London: Penguin.

Goode E, Ben-Yehuda N. Moral Panics: The Social Construction of Deviance. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 1994.

Greenland, S., Last. J.M., and Porta, M.S.(2008) A dictionary of epidemiology, New York: Oxford University Press.

Kaduszkiewicz, H., Bachmann, C., and van den Bussche, H. (2008) “Telling “the truth” in dementia-Do attitude and approach of general practitioners and specialists differ?”, Patient Education and Counseling, vol. 70, no. 2, pp. 220–226.

Korczyn, A.D., and Vakhapova, V. (2007) “The prevention of the dementia epidemic”, J Neurol Sci, 15. pp. 257(1-2):2-4.

Massumi, B. (2007) The future birth of the affective fact: the political ontology of threat forthcoming, in Pollock ,G. (ed ), The ethics and politics of virtuality and indexicality, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mattsson, N., Brax, D., and Zetterberg, H. (2010) “To know or not to know: ethical issues related to early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease”, Int J Alzheimers Dis,. pii: 841941.

Navarro, Z. (2006) ‘In Search of Cultural Intepretation of Power’, IDS Bulletin 37(6): 11-22.

Nepal, B., Ranmuthugala, G., Brown, L., and Budge M. (2008) “Modelling costs of dementia in Australia: evidence, gaps, and needs”, Aust Health Rev, 32(3), pp. 479-87.

Paradis, E. (2011) Changing meanings of fat: Fat, obesity, epidemics and America’s children, Stanford University unpublished dissertation.

Paradis, E., Albert, M., Byrne, N., and Kuper, A. (2012) Changing Meaning of Epidemic and Pandemic in the Medical Literature, 1900-2010. American Sociological Association Conference, Denver, CO: August, available at: http://www.eliseparadis.com/files/EoE-DenverV1.pdf.

Saguy, A.C., and Almeling, R. (2005) ‘Fat devils and moral panics: news reporting on obesity science.’ Presented at the SOMAH workshop. UCLA Department of Sociology. June 1.

Sosa-Ortiz, A.L., Acosta-Castillo, I., and Prince, M.J. (2012) “Epidemiology of dementias and Alzheimer’s disease”, Arch Med Res., 43(8), pp. 600-8.

Stephan, B., and Brayne, C. (2008) Prevalence and projections of dementia, in: Excellence in Dementia Care: Principles and Practice (eds. Downs, M. and Bowers, B), Maidenhead (UK): Open University Press (McGraw-Hill Education).

Strech, D., Mertz, M., Knüppel, H., Neitzke, G., and Schmidhuber, M. (2013) “The full spectrum of ethical issues in dementia care: systematic qualitative review”, Br J Psychiatry, 202, pp. 400-6

Treves, T.A., and Korczyn, A.D. (2012) “Modeling the dementia epidemic”, CNS Neurosci Ther., 18(2):175-81.

Wimo, A., and Winblad, B. (2004) “Economic aspects on drug therapy of dementia”, Curr Pharm Des, 10, pp. 295-301.