There are 800,000 people living with dementia in the UK, it is thought.

There is no cure at the moment.

“Attitudes are changing. The old stigma is being replaced by the recognition that people with the disease can be helped.”

Later on, John Humphrys spoke this morning to a number of clinicians involved in managing persons with dementia.

The package begins with an initiative called ‘Singing for the brain’.

Singing for the Brain is a service provided by Alzheimer’s Society which uses singing to bring people together in a friendly and stimulating social environment.

The power of music, especially singing, to unlock memories and kickstart the grey matter is an increasingly key feature of dementia care. It seems to reach parts of the damaged brain in ways other forms of communication cannot.

Organisations such as Music for Life, Lost Chord, Golden Oldies and Live Music have also improved accessibility live musicians, both professional and amateur, most of them trained to deal with the special needs of an elderly, memory-impaired audience.

A nice overview of some of these initiatives is given on the Age UK website.

The way in which the brain might do this is indeed interesting.

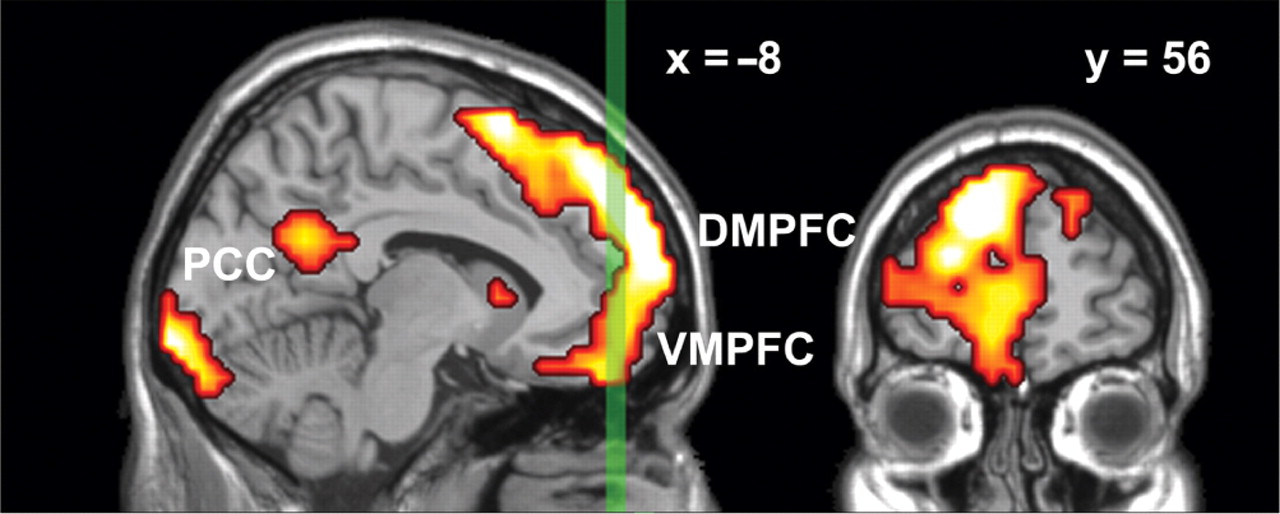

Results from Petra Janata (1999) suggest that the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) associates music and memories when we experience emotionally salient episodic memories that are triggered by familiar songs from our personal past.

MPFC acted in concert with lateral prefrontal and posterior cortices both in terms of tonality tracking and overall responsiveness to familiar and autobiographically salient songs.

The MPFC is right at the front of the brain.

My interpretation using the “bookcase analogy” of “Dementia Friends” is that while the bookcase representing your memories for events is shaking this bookshelf representing memories triggered by music is unaffected.

It’s virtually the same as the bookcase responsible for sporting memories, in my view of things.

I wonder if ability to reactive sporting memories is correlated with ability to reactivate music memories?

This would explain the efficacy of this approach to living well with dementia.

We not only have to face the reality of the scope of people living with dementia in society.

But as Humphrys articulates in his item.

“Part of it is how society is set up to respond to people who look confused… instead of reacting in a fearful way, we are thinking in terms of how to help such people”, so comments Dr Andrew Crombie from South West London and St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust.

You can listen to the whole of the presentation by John Humphrys – for one week only from the date of this blogpost – on the BBC iPlayer.

Play from about 1 hr 34 mins in on this page.

Social stigma is the extreme disapproval of (or discontent with) a person or group on socially characteristic grounds that are perceived, and serve to distinguish them, from other members of a society. Stigma may then be affixed to such a person, by the greater society, who differs from their cultural norms.

Social stigma can result from the perception (rightly or wrongly) of mental illness, physical disabilities, diseases such as leprosy (see leprosy stigma), illegitimacy, sexual orientation, gender identity, skin tone, education, nationality, ethnicity, ideology, religion (or lack of religion[3][4]) or criminality. Attributes associated with social stigma often vary depending on the geopolitical and corresponding sociopolitical contexts employed by society, in different parts of the world.

According to Goffman in “Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity”, there are three forms of social stigma:

- Overt or external signs, such as scars

- Deviations in personal traits, including forms of medical conditions

- “Tribal stigmas” are traits, imagined or real, of ethnic group, nationality, or of religion that is deemed to be a deviation from the prevailing normative ethnicity, nationality or religion.

Prof Alistair Burns is the National Clinical Lead for dementia for NHS England, and was interviewed by John Humphrys this morning.

“You have highlighted very well in the discussions today and yesterday .. about something which we hear much more of now, and that is: people can live well with dementia. On the interview yesterday, we heard from Linda who felt she was very supported by her friends yesterday, and you said that when you interviewed Grace she felt normal.”

Humphrys was concerned that this was only representative of people living with dementia in the earliest stages.

Burns said, “There are many things that we can do, whatever the stage of dementia.”

“If we look at person-centred care, that is treating people as individuals we’ve heard from ‘Singing for the brain’ and ‘Life Story Work’ can bring people together.”

And have we been doing this successfully thus far?

“It’s fair to say that there has been pockets of excellent work being done around the country.. And one of the things which we must do is to encourage people to do and to learn from areas which are doing well like the example we saw yesterday, and like the example we saw today.”

Humphrys then went on to probe Burns much more about the stigma.

“We know that, from surveys of people for people above the age of 55, dementia is the most feared disease, much more than, say, stroke, heart disease or cancer.”

“There is something about the stigma. What we have seen is a lessening of the stigma, things like ‘Dementia Friends‘, working with schools, and getting ideas into schools.”

Humphrys proposed that it is necessary was to get rid of the idea that there was something about dementia that is “shaming”.

“What you got yesterday from today and yesterday was that people felt normal and supported. But I hear from my own clinic that, experiences where once people receive a diagnosis of dementia, others cross the street.”

“And trying to wrestle that is important.”