Is this dress black and blue or gold and white?

The background colour of daylight varies during the time of day.

That colour axis varies from the pinkish red of dawn, up through the blue-white of noontime, and then back down to reddish twilight.

People who see white and gold may be looking at the dress in a blue-lit room or near a window with a blue sky. It also depends on our own individual sensitivity to the bluish tinting in the photo. The brains of people who see white and gold are interpreting the photo as more shadowy. The brain compensates for the darker blue tinting and interprets the blue part as white and the black part as gold.

So we all do see the dress differently.

This phenomenon is known as “colour constancy”.

Colour constancy is an example of subjective constancy and a feature of the human colour perception system which ensures that the perceived colour of objects remains relatively constant under varying illumination conditions.

A green apple for instance looks green to us at midday, when the main illumination is white sunlight, and also at sunset, when the main illumination is red. We don’t want the colour of objects appearing to change as the day progresses?

The physiological basis for colour constancy is thought to involve specialised neurones in the primary visual cortex that compute local ratios of cone activity.

Colour constancy works only if the incident illumination contains a range of wavelengths.

The different cone cells of the eye register different but overlapping ranges of wavelengths of the light reflected by every object in the scene. From this information, the visual system attempts to determine the approximate composition of the illuminating light. This illumination is then discounted in order to obtain the object’s “true colour” or reflectance: the wavelengths of light the object reflects. This reflectance then largely determines the perceived colour.

These cone cells are the colour-sensitive cells of the retina (comparable to the “film” in a camera). The non-colour sensitive cells are called rods. This is what a cone looks like under a microscope.

The same phenomenon underlies the “Mondrian panel” – where the colour of a square depends on the colour of the squares around it. Pieter Cornelis “Piet” Mondriaan (March 7, 1872 – February 1, 1944), was a Dutch painter. He was an important contributor to the De Stijl art movement and group, which was founded by Theo van Doesburg. He evolved a non-representational form which he termed neoplasticism. This consisted of white ground, upon which was painted a grid of vertical and horizontal black lines and the three primary colours.

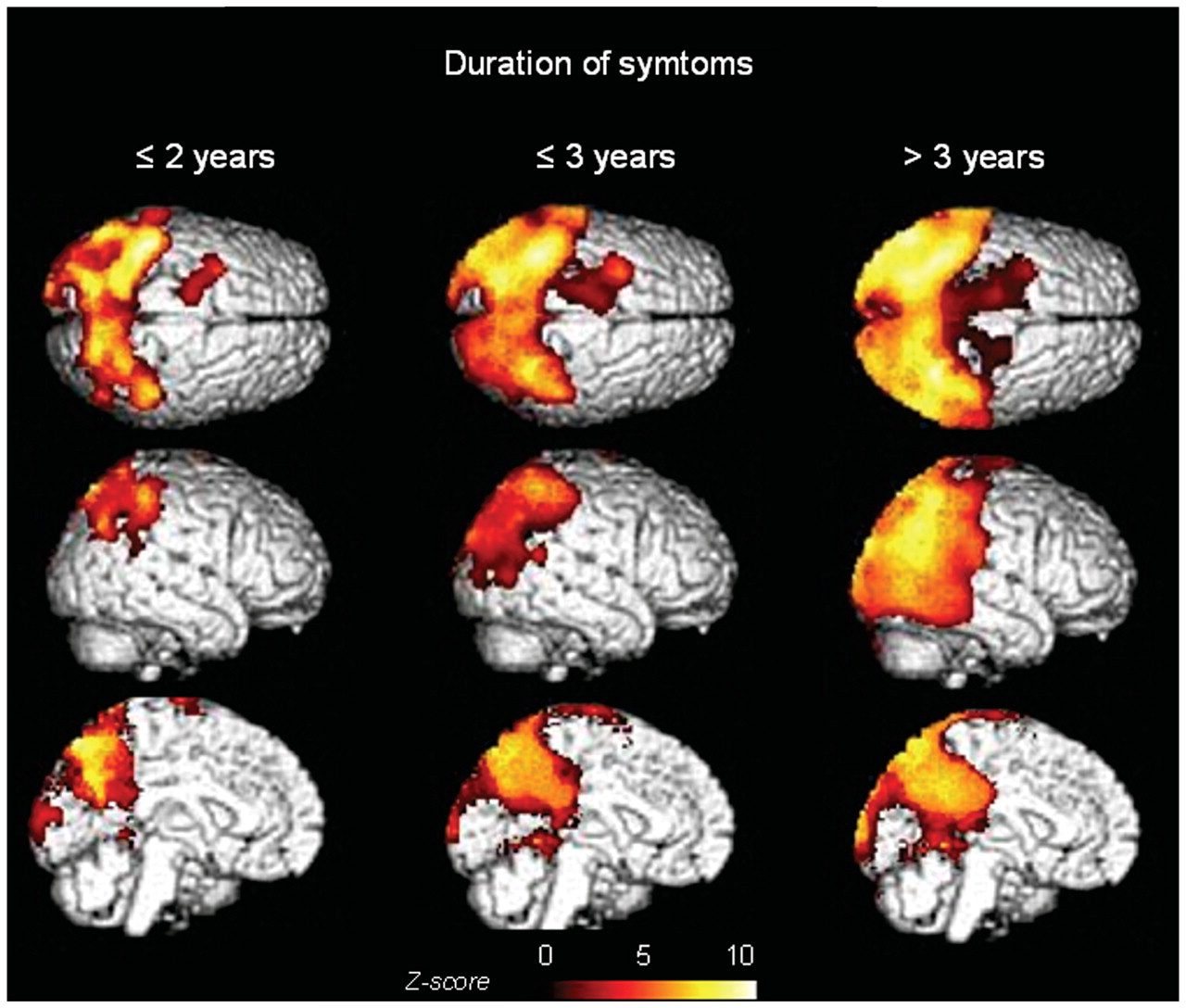

And central processing of colour is not thought to be affected early on in the dementia of the Alzheimer type, as the memory part of the brain (hippocampus) is in a different part of the brain involved in processing colour (the occipital part of the brain). That’s why we do desperately need some evidence-based neuroscience looking at colour in so called “dementia friendly communities”, otherwise the field will be riddled with speculation, anecdote and rumour.

Posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) is different. In “Dementia Friends”, we are told that dementia is not just about losing your memory – indeed in early PCA the common presenting problem can be that of visual perception rather than memory. It’s not uncommon for people with this form of dementia to go round the houses seeing opticians rather the memory clinic/cognitive disorders clinic.

As stated here,

“The symptoms of PCA can vary from one person to the next and can change as the condition progresses. The most common symptoms are consistent with damage to the posterior cortex of the brain, an area responsible for processing visual information. Consistent with this neurological damage are slowly developing difficulties with visual tasks such as reading a line of text, judging distances, distinguishing between moving objects and stationary objects, inability to perceive more than one object at a time, disorientation, and difficulty maneuvering, identifying, and using tools or common objects. Some patients experience hallucinations. Other symptoms can include difficulty performing mathematical calculations or spelling, and many people with PCA experience anxiety, possibly because they know something is wrong. In the early stages of PCA, most people do not have markedly reduced memory, but memory can be affected in later stages.”

However, there are specific dementia syndromes which can conceivably affect that part of the brain. Chan, Crutch and Warrington (2001) reported an intriguing 64 year old woman with posterior cortical atrophy. Her presenting symptom was of seeing objects as abnormally coloured after prior exposure to a coloured stimulus. Formal testing disclosed that the patient experienced colour after-images of abnormal latency, duration, and amplitude.

Indeed the description of the methods in the paper makes reference to Mondrian panels.

A general theme is that living better with dementia is the result of an exquisite interaction between the facets of a person (personhood) and the wider environment at large.

It would be low hanging fruit to see if a population of people living well with posterior cortical atrophy see the dress differently to people in the general population. We know we tend to see that dress differently, but are the ratios of the black/blue – gold/white different in people living well with posterior cortical atrophy?