A curious thing happened when I was taking a taxi back home from the Royal Free Hospital in Hampstead. The taxi driver, somebody I first met several years ago in fact, reminded me that he is a father of two children living with autism. But he presented the information as if he was telling me some catastrophic news.

I have kept in touch with Prof Simon Baron-Cohen’s work, as Director of the Autism Research Centre at Cambridge, not least because Simon was my first ever supervisor there. I did a study with him on the genetics of synaesthesia, a condition where a person might see a colour in his mind’s eye on hearing a word.

Baron-Cohen has advanced the approach that people living with autism, whilst poor at empathy processing, tend to be very good at big picture systemisation planning. People with autism can flourish in highly mathematical and technical disciplines. Einstein, it is remarked, was poor at interactions with other children once and exhibited a symptom called ‘echolalia’ in speech, which can be a symptom of autism.

Dementia is an umbrella term referring to more than a hundred different conditions of the brain which can produce cognitive and behavioural symptoms over time, not just in memory. But imparting the diagnosis of dementia embraces the ‘cliff edge’ nature of dementia – that one moment you might not fit the diagnostic criteria, the other moment you do. Therefore, ‘having dementia’ is an all or nothing phenomenon, and has a sense of finality.

This sense of finality, however, can be very destructive. Kate Swaffer, Chair of Dementia Alliance International, has described the impact of the diagnosis as a disempowering experience. Many people with dementia experience social isolation and loneliness on diagnosis. As a likely result of the stigma of the diagnosis of dementia, dementia has become one of the most feared conditions in adulthood.

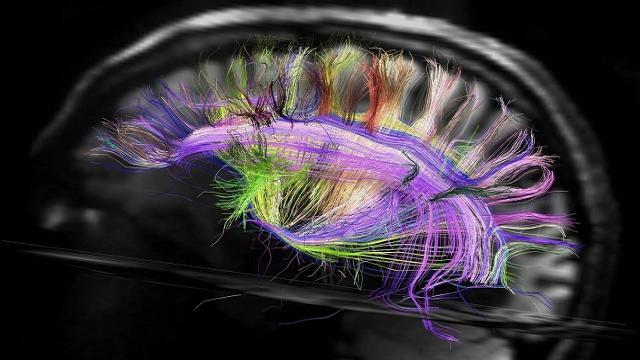

But I feel dementia inherently can be thought of using an approach of ‘neurodiversity’. Whilst dementia is not a mental illness, but rather a condition of the brain, we are acknowledging the diverse aspects of mental function already say in ADHD, autism and schizophrenia. Neurodiversity is a phenomenon akin to biodiversity, of species with varying adaptive traits, and the broad range of neurodiverse phenotypes makes as a whole a resilient population.

It is a matter of speculation what dementia might be adaptive for, but, people with ADHD, with distractibility and hyperactivity, might, theoretically, exhibit traits which are adaptive for the hunter-gatherer population.

I feel as another Dementia Awareness Week draws to a close that we are in a much better place with dementia than where we were only a few years ago. People on the whole are no longer ashamed to be living with dementia. As Dr Jennifer Bute said in a BBC programme last week, it’s not the challenge itself of interest of the diagnosis of dementia, but the personal reaction to that challenge.

This has led to a situation where people with dementia are respected for what skills and lifelong experience and wisdom they can bring to the table. This strength based approach is fundamentally different to the one which purely focuses on deficits.

I have no doubt, personally, that an approach which emphasises human rights for people living with long term disabilities is a right one. The UN Convention on Rights for People with Disabilities, whilst not explicitly mentioning dementia, clearly is supposed to embrace conditions such as dementia.

It is right that if a disability in cognitive function is identified it should be rectified through some sort of adaptation or adjustment. That is the purpose of the “PANEL” human rights approach globally, which implements equality non-discrimination and accountability.

But gone are the days when one size fits all, and that’s where the “neurodiversity” approach, celebrating skills and abilities as well as disabilities, comes in. I feel that embracing diversity of all people, in an inclusive way, is necessary and sufficient for breaking down stigma.

It is intuitive that we don’t want a population where we rank people on how fast they get to the same solution, even though this is what academic assessments at school and university appear to do. We should, instead, be encouraging a society where people can legitimately offer different things. This is not a question of ‘all shall have prizes’, but rather adopting an approach where success builds on success.

And if someone’s cognitive profile changes, that person with dementia should have inalienable universal rights to ensure that he or she can live as fulfilling life as possible. It is worth noting that this approach is entirely valid irrespective of whether a cure for dementia is found before 2025.