There’s been a lot of heat and frustratingly little light in the discussions in where the delays might occur in disclosing a diagnosis of a possible dementia. At worst, politicians and influential others (largely not medically qualified) have given the impression of ‘coasting’ GPs slowing down the process. But this would be to simplify an extremely complicated issue in such a way that causes considerable damage in English policy concerning dementia.

There are significant differences in the percentage of people with dementia receiving a diagnosis in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In 2012, for example, it was estimated that 39 per cent of people in Wales had a diagnosis, 44 per cent in England and 63 per cent in Northern Ireland. As a result, the prime minister’s challenge on dementia aimed to increase diagnosis rates by two thirds by 2015, and the Scottish Government launched a similar initiative. Last year, a paper first presented in September at the “Preventing Overdiagnosis conference” in the United States – and subsequently published in the BMJ – suggested that the drive to screen people for minor memory changes, often called pre-dementia or mild cognitive impairment, risks doing more harm than good.

The authors, led by David Le Couteur, professor of geriatric medicine at the University of Sydney, warned that expanding diagnosis in dementia would result in up to 65 per cent of people aged over 80 being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, and up to 23 per cent of older people being wrongly labelled as having dementia. The authors argued that the trend for screening older people for minor memory change in the UK and the US is leading to unnecessary investigations and potentially harmful treatments; and that is diverting resources that are needed to care for people with advanced dementia. However, the benefits of a timely diagnosis are seen to be longer periods of higher quality life supported at home. Major consequential savings in hospital in-patient and residential social care costs are anticipated. Policies are favoured that deliver personalised support packages for people living at home, it is hoped, night be contemplated at the earliest juncture.

There are currently international variations in the opinions of family members and informal carers about whether they believe a diagnosis should be given to their loved ones. The obvious tension between doing no harm and giving people the right to make a decision about whether they wish to receive their diagnosis is an important bioethical debate. A study conducted in Brazil (Shimizu et al 2008) found that only 58 per cent of carers of people with dementia believed the diagnosis should be disclosed. In a similar study in Taiwan, this number was 76 per cent (Lin et al 2005) and in a study in Finland (Laakkonen et al 2008), 97 per cent of carers believed diagnosis should be disclosed to their relative. A study in Belgium (Bouckaert and van den Bosch 2005) found only 43 per cent of relatives supported disclosure, while in Italy, Pucci et al (2003) found only 39 per cent of relatives favoured disclosure. While the reasons for this global disparity are unclear, these are important considerations for nurses to be aware of before engagement with families of people with dementia. This disparity is perhaps a reflection on the uniqueness of people with dementia as well as the attitudes and feelings of their families.

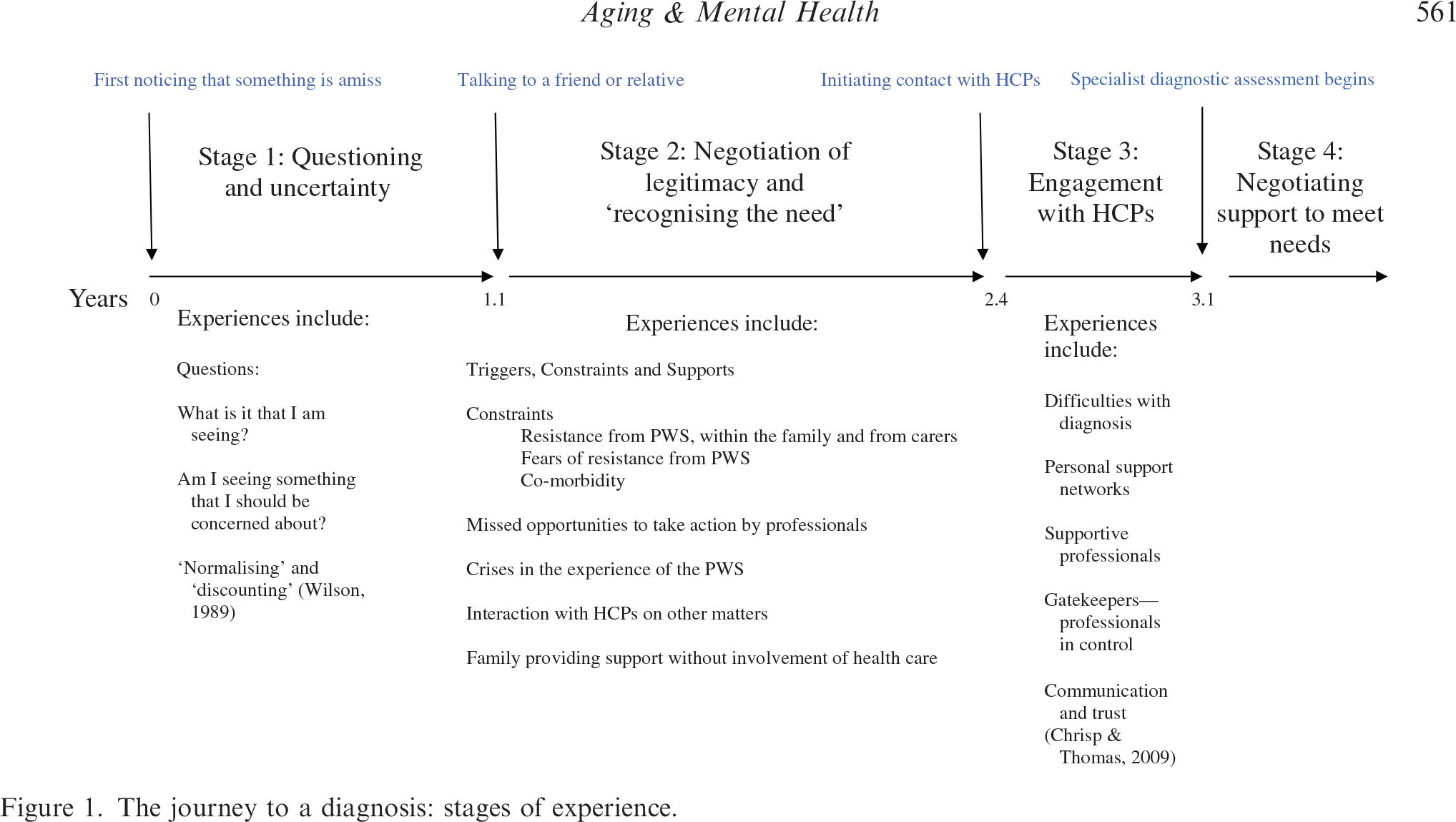

The present interest in the UK in bringing forward diagnosis of dementia requires insights into the journey taken by people with dementia and carers on their way to reaching a diagnosis. (Please note that there are some persons with dementia who’ve said publicly in the past in the social media, “I am not on any journey.”) Early work had described a timeline of changes and events that occur during the journey of a person with dementia and their carers – in particular: first noticing that something may be amiss, first talking to a friend or family member about it; stopping driving; needing help with daily activities; first contact with a physician and receipt of a diagnosis. Key findings from that earlier work are that it took on average 1 year for the carer or the person with symptoms (PWS) to talk to a friend or family member.

An important aim of a paper by Tom A.C. Chrispa, Sharon Tabberer, Benjamin D. Thomas and Wayne A. Goddard, entitled “Dementia early diagnosis: Triggers, supports and constraints affecting the decision to engage with the health care system”, published in Aging & Mental Health [Vol. 16, No. 5, July 2012, 559–565] was to identify influences on people’s decisions to make first contact with an HCP. The data suggest that carers of people with the symptoms of dementia who live at home are very often the ones to generate the first action to contact an HCP.There is very often a lengthy delay between first noticing symptoms of dementia and making first contact with Health Care Professionals (HCPs). This article identified influences on the decision to contact HCPs for the first time through a ualitative thematic analysis of 20 case studies of carer experience. Participants were carers of people who attended Memory Clinic services.

In only 2 of their 20 cases did the PWS actively make the first contact with an HCP to discuss their symptoms. In 13 cases, the carer was the main agent effecting the first engagement with HCPs. In one case, the carer and a social worker were closely involved together in deciding to engage HCPs. In three cases, a medical professional directly prompted a discussion with other HCPs about the issue. In one case, a non- medical professional initiated the first contact with HCPs.

A diagram of their key stages is helpfully provided by the authors:

Stage 1. The time between thinking something may be amiss and the time of first talking to a friend or relative about this.

This stage is on average 1 year in length. It is a period where the carer has noticed that something is amiss but they have yet to articulate their concerns. Delays in contacting others may arise due to carer’s fears of the resistance that the PWS may have towards the involvement of HCPs. The demands that other medical conditions place on carers can also provide a distraction.

Stage 2. The time between first talking to a friend or relative about this and first contacting an HCP to discuss the symptoms.

This stage is on average 1 1/3rd years long. Family members may resist the involvement of HCPs. Sometimes, it was the carer themselves and sometimes, it was other family members who resisted involving HCPs. There were debates among family members about what was being observed. An issue might be: “Is it just ‘old age’?” Families might on occasion disagree about the nature of symptoms but agree that care was needed and provide additional care support at home without involving HCPs. Sometimes the internal discussions concluded that the symptoms were not caused by a ‘health problem’.

Interestingly, the authors report that carers did not always recognise at first that HCP involvement might be an appropriate response to the behaviours being witnessed. Sometimes, it is a ‘trigger’ (an event, a build up of evidence) that is required to enable the carer to feel they have the necessary legitimacy to contact HCPs.

So it is clear from this initial paper that this unsightly slanging match between professionals, the public and politicians might be barking up completely the wrong tree. The dynamics in the relationship between the person with symptoms, and those closest, who might include friends and family, are undoubtedly critical, and I’ve been struck how this might be particularly important in the early onset dementias. In an important paper entitled, “The experience of caring for a partner with young onset dementia: How younger carers cope”, by Shirley Lockeridge and Jane Simpson in the journal Dementia, the authors describe explicitly a phenomenon of: “‘This is not happening’: carers’ use of denial as a coping strategy.” For example, in the behavioural variant of the frontotemporal dementia, the presentation is not problems in memory, but rather an insidious change in behaviour and personality noticed primarily by others not the person himself or herself. And possible explanations offeredfor the changes in the behaviour and personality of their partner, according to Lockeridge and Simpson, have been rather varied, including post-viral fatigue, a brain tumour, stress at work and a ‘mid-life crisis’:

However, according to the authors, as time passed, younger carers and their partners began to adopt more emotion-focused strategies:

“This originated in the reluctance of their partner to acknowledge that they were experiencing any problems which meant that most carers had to use excuses and subterfuge in order to persuade their partner to attend medical appointments and assessments. Carers found that they experienced increasing anxiety as their partner’s behaviour deteriorated and their need increased to have clandestine discussions with their GP, with employers and with banks to take control of financial matters. Carers described using avoidance as a way of coping with the changes in their partner and spoke of behaving like an ‘ostrich’, ‘burying their head in the sand’ and ‘pretending’ that their partner’s problems were not serious. Carers were also acutely aware of their partner’s denial of their symptoms and described feeling as if they were adopting a ‘cloak and dagger’ approach to hide any information about dementia from their partner. Carers reported trying to maintain everything as ‘normal’, even up to the point of diagnosis.”

In an equally intriguing paper, “The personal impact of disclosure of a dementia diagnosis: a thematic review of the literature” by Gary Mitchell, Patricia McCollum and Catherine Monaghan in the British Journal of Neuroscience Nursing [October/November 2013 Vol 9 No 5]. the authors reviewed that decisions around disclosure of a diagnosis of dementia are not always patient-centred. The authors argued that a plethora of literature supports the notion that physicians do not always clearly and directly disclose the diagnosis to the person with dementia. The authors found that Bamford (2010) had suggested that the global rate of non-disclosure is around 40%. There are several reasons for this, but arguably the most pertinent is the emotional distress disclosure can potentially cause. This emotional impact can undoubtedly a crucial factor in carers’ attitudes and practitioners’ variability in disclosing the diagnosis to their patients, it is argued (Robinson et al, 2011).

The findings of this review indicate that people who have recently experienced a diagnosis of dementia have feelings ranging from anxiety or fear to relief, or the enablement of future planning. Despite this mixture, the perceived stigma surrounding a diagnosis of dementia was evident in the majority of the literature. The act of non-disclosure, which is common globally, is a decision often taken by physicians or carers in a bid to promote non-maleficence (“do no harm”). The authors argued that numerous studies have demonstrated that family or physicians often conclude that beneficence or non-maleficence out- weighs the person’s autonomy and that a disclosure of the diagnosis of dementia to the person will cause harm; by withholding this knowledge the physician and/or family believe they are collectively doing good.

Non-disclosure can also be analysed through the prism of Tom Kitwood (1997) and his model of “malignant social psychology”. Malignant social psychology pertains to an environment where the person with dementia is treated differently owing to their being diagnosed with dementia (Kitwood, 1997). Key components of this model are disempowerment, infantilisation and withholding. Through non- disclosure, people with dementia have their diagnosis withheld by physicians or carers because of the poten- tial harm it could cause (infantilisation). This can ultimately serve to make the person with dementia more passive in their care (disempowerment).

There has been unsightly amount of finger pointing as to “who is to blame”. Often in the firing line is ‘primary care’ as the point of first point of contact for people with suspected dementia in ensuring early detection and effective ongoing management. Collaboration between general practices and specialist services is therefore essential to ensure a smooth pathway to diagnosis. Collaborative care is essential in the management of long term conditions, but joined-up working between specialist dementia services such as memory clinics does not appear to be comprehensive or universal. Memory service investment and access varies hugely across the UK. And with the current implementation of the Health and Social Act (2012), acting as a driver to privatised, fragmented services, there is a genuine risk this will get worse.

Furthermore, evidence reveals that the average UK consultation time varies from 7.4 to 11.7 minutes. As older people often present with complex health and social care needs, length of appointment time may be a barrier in meeting their diverse needs. Furthermore, there are people susceptible to dementia who may not have access to a GP or specialist support services such as those from deprived populations, the oldest old people or those without support networks. For true inclusivity and equitable access to health care, services might need to be much proactive in reaching out to those in communities who remain unregistered with general practice and lack access to care, regardless of social and cultural background and geographical location, and also taking into account cultural barriers to diagnosis.

The role of the nurse in raising awareness and improving the lives of persons with dementia has recently been come under sharp focus.While GPs may not be able to pick up on the early signs and symptoms of dementia with the constraints posed by the general practice setting, nurses work at the interface between the patient and their social environment and are therefore well placed to notice the early signs and symptoms of dementia . Prof. June Andrews, director of the Dementia Services Development Centre at the University of Stirling, and a former director of nursing, has argued clearly that she understands that testing for dementia at an early stage carries risks – but they are risks she would be willing to take.

Professor Andrews would like to see a greater role for nurses in dementia diagnosis, both in hospitals – particularly A&E – and the community.

“The logical and humane way forward is to emphasise the role of the nurse. The usual diagnosis points – GPs and psychiatrists – can be high quality, but you sometimes end up with a backlog, which means that people do not get the benefit of diagnosis. The risks of nurse-led diagnosis are small.”

An example of successful, collaborative working in practice is the Community Dementia Nurse (CDN) Service launched by 2gether NHS Foundation Trust (2011) in Gloucestershire. The CDN service is innovative in providing specialist and direct support regarding dementia to GPs.The role covers advice and support with diagnosis, management and treatment of dementia and care plans designed to address immediate care needs. However, this is targeted at those within populations who have access to GP surgery.

So, this is most definitely ‘work in progress’. The frustration of many who have felt that the diagnosis of dementia has been unnecessarily delayed is a very serious one. But blame is not particularly constructive, nor motivating for a service already at full stretch. And it is clear now that the problem embraces a number of problems, not confined to education and training standards of the current NHS workforce, but the extent to which those closest to people with dementia-like symptoms might prefer themselves the diagnosis not to be one of dementia. For example, a subtle change in personality could be a ‘mid life crisis’, but it might be as politically offensive to suggest this soon for danger of being bundled with dementia symptoms being misattributed as ‘normal ageing’.

The irony is that, while medical professionals cannot offend the key medical ethical principle of ethics, if persons have full capacity as far as the law is concerned (but have dementia-like symptoms), in the form of ‘coercive behaviour’, access to care or cure could in future decades come in a rather personalised form, whether this is personalised medicine or a personal-health budget.

References

Bamford C, Lamont S, Eccles M, Robinson L, May C, Bond J (2004) Disclosing a diagnosis of dementia: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 19(2): 151–69.

Bouckaert F, van den Bosch S (2005) Attitudes of family members towards disclosing diagnosis of dementia. International Psychogeriatrics. 17, Suppl 2, 216.

Kitwood, T. (1997). Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first. Buckinghamshire: Open University

Press.

Laakkonen M, Raivio M, Eloniemi-Sulkava U et al (2008) How do elderly spouse care givers of people with Alzheimer disease experience the disclosure of dementia diagnosis and subsequent care? Journal of Medical Ethics. 34, 6, 427-430.

Lin K, Liao Y, Wang P et al (2005) Family members favor disclosing the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. International Psychogeriatrics. 17, 4, 679-688.

Pucci E, Belardinelli N, Borsetti G et al (2003) Relatives’ attitudes towards informing patients about the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Medical Ethics. 29, 1, 51-54.

Robinson L, Gemski A, Abley C et al (2011) The transition to dementia–individual and family experiences of receiving a diagnosis: a review. Int Psychogeriatr 23(7): 1026–43

Shimizu M, Raicher I, Takahashi D et al (2008) Disclosure of the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: caregivers’ opinions in a Brazilian sample. Arquivos de Neuro-psiquiatria. 66, 3B, 625-630.