Tomorrow is in fact the day of the ‘Legal Aid walk’ – the annual event where law firms, law students, barristers, solicitors and supporting staff take to the streets in the heart of London to walk a fair old distance in support of legal aid and access to justice.

This is very timely. Law is one of my strong interests; so is dementia. I am in fact trained in both. This is why the imminent plan to repeal the Human Rights Act 1998 is of great significance to me. I have written previously on the huge importance of rights based approaches to dementia in my blogpost here, and I have even devoted a full chapter on it on my new book on domestic and global dementia policy. But even academic lawyers would be the first to admit they’re not astrologers; the future of the legislation on human rights is clearly unchartered territory even now.

There will be very many accounts of the view that repealing the Human Rights Act is a backward step in the law, many given by many eminent lawyers. I do not want to go over the same ground here, but needless to say they are widely available; such as by Philippe Sands or Keir Starmer.

The Conservative Party’s plan to establish a Bill of Rights to replace the Human Rights Act has helpfully been published. It was a clear manifesto pledge. If the opinion polls were correct, no one party expected to win the general election outright, so it’s quite likely the Conservative Party wished to lose the pledge on abolition of human rights to negotiation with the Liberal Democrats, for example. It is currently reported that the SNP wish to ‘fight attempts to abolish the Human Rights Act’. And it has been a longstanding commitment of the Scottish jurisdiction to promote ‘rights based approaches‘ in dementia for people with dementia and carers.

Whatever happens in the term of this parliament is unpredictable. Whilst the “Salisbury convention” provides that manifesto pledges should see the light of day on the statute books, it is also clear that there is a significant number of peers who will not condone abolition of the Human Rights Act. Lord Lester, a Liberal peer, has made it clear on the BBC Radio 4 programme that he does not want to make ‘wrecking amendments’, but takes the attitude that he does want to make the proposals ‘better law’. The Conservative Party have tried to send out the message that the proposed change in the law is not to abolish human rights, but the fact that Labour have just appointed Lord Charlie Falconer QC to spearhead the charge of the brigade as Shadow Lord Chancellor and Shadow Minister of Justice is very telling. Lord Falconer was indeed one of the architects of the original Human Rights Act under a previous administration. All it needs is for a “magnificent seven” in number to rebel; probably the Democrat Unionist Party are not the ones too, but ‘grandees’ with a legal training Ken Clarke QC MP and Dominic Grieve QC might.

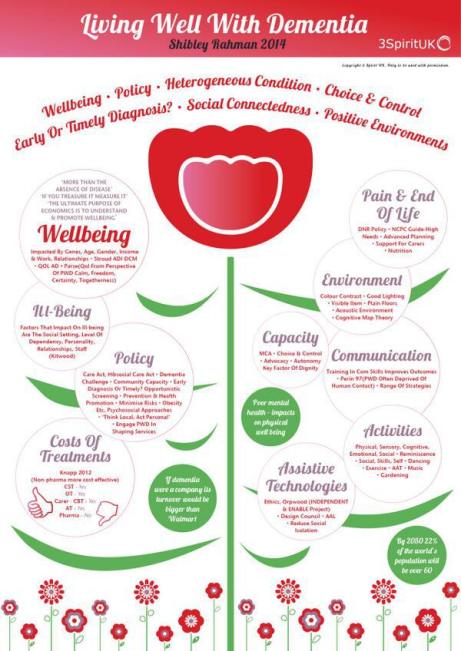

Changes to the law theoretically offer an opportunity to include new ‘rights’, such as the right to a timely diagnosis of a medical condition. It is critical to note that not all rights in rights based advocacy for dementia come from human rights; there are rights in equality law which mitigate against discrimination, and rights in employment law which mitigate against unfair dismissal, for example. It is also important to note that not all rights are legal; for example it was morally repulsive to allow segregation under Apartheid in South Africa before a change in the law was afforded. There is therefore some basis to the messaging that rights existed before the Human Rights Act; they have done so since the Magna Carta in fact.

And rights have to be enforceable. At the moment, in England, there is a huge problem with access to justice, hence the importance of such initiatives such as the Legal Aid Walk. Legislation from the previous government in the form of the Legal aid and sentencing and punishment of offenders act 2012 was hugely detrimental for this cause, with concomitant destruction of law centres. Human rights are indeed enforceable through, for example, the High Court under judicial review, or through the Equality and Human Rights Commission.

But the critical thing about human rights is that they’re not as such ‘British rights’. They’re international, inalienable, available to everyone – they’re universal. Whilst we are still signatories to the European Convention on Human Rights, any British citizen is free to petition Strasbourg directly over an issue to do with human rights; it would be a huge deal if the UK sent out a message that it no longer wished to be a signatory of the Convention when it was originally one of its architects. Even with abolition of the Human Rights Act (1998) in this jurisdiction, dementia can still come under disability under the UN Convention for People with Disabilities (“UKCPD”). This statutory instrument has a whole host of rights, including the right for democratic representation and right to participate in public life (article 29) ( which the World Dementia Council would be wise to read). The UK may or may not be under current investigation for breaches of the UKCPD, and we are in any case observing the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights.

These rights are wide-ranging and important for our political narrative. They’re relevant to our discussion of capacity, that people with dementia have human rights regardless of their capacity (related cases such as the Bournewood Gap are particularly important here). Such rights are relevant to various issues, such as “independent living”, and we can learn a lot from the wider disability movement here (such as the brilliant work of John Evans). As indeed human rights are important for the devolution and Good Friday agreements, the discussion over human rights indeed embraces a wide range of stakeholders involved in dementia policy, such as SCIE, where dignity is intimately related to a right to be free from degrading treatment (see their guidelines). And unsurprisingly human rights are totally pervasive to the work of the Care Quality Commission. The success of human rights has been much to do with motivating a ‘social movement’, imbuing a sense of ‘rights consciousness’ in keen followers around the world.

I personally am a big advocate of ‘bounded rationality‘ in strategising about the future, in dealing with risk and uncertainty. The discussion over human rights is clearly politically driven, but is essentially for me about protecting those people who are most vulnerable too. Living better with dementia policy is much enhanced with a rights based approach. Some strands in the debate are rational; some less so. But we are living in uncertain times, and political tensions are high. Soon places of the jigsaw will fall into place, and we will all be able to deal with it at the time.