My tweet on this – including Hilary Evans’ excellent explanation – is as follows.

good expl. by @HilaryAlzUK – gamification of spatial cognition is v relevant to the hippocampal problems in Alz D https://t.co/naLsSqVBPp

— Dr Shibley Rahman (@dr_shibley) May 5, 2016

Sea Hero Quest was launched today by Alzheimers Research UK. It has been developed by London based studio Glitchers and follows a captain as he tries to recover his father’s lost memories. You navigate the boat but there’s no mini-map within the level, you’re given all the locations to visit at the start of the game from a map.

The link to the app is here.

Here’s a typical screenshot from the game.

I downloaded the game for free onto my iPad. It was easy to get into – I quite liked the option also of not sharing the data from my experiments too, but the notion of contribution to a giant experiment through ‘gamification’ is also extremely appealing to many.

I really don’t see how X minutes of playing the game can equate to Y minutes of ‘traditional research’ – but I am not in the least bit bothered about that.

The game was not what I expected it to be. Searching for objects in a task in humans is well known to people who experiment with primates – it’s officially known as a spatial working memory task.

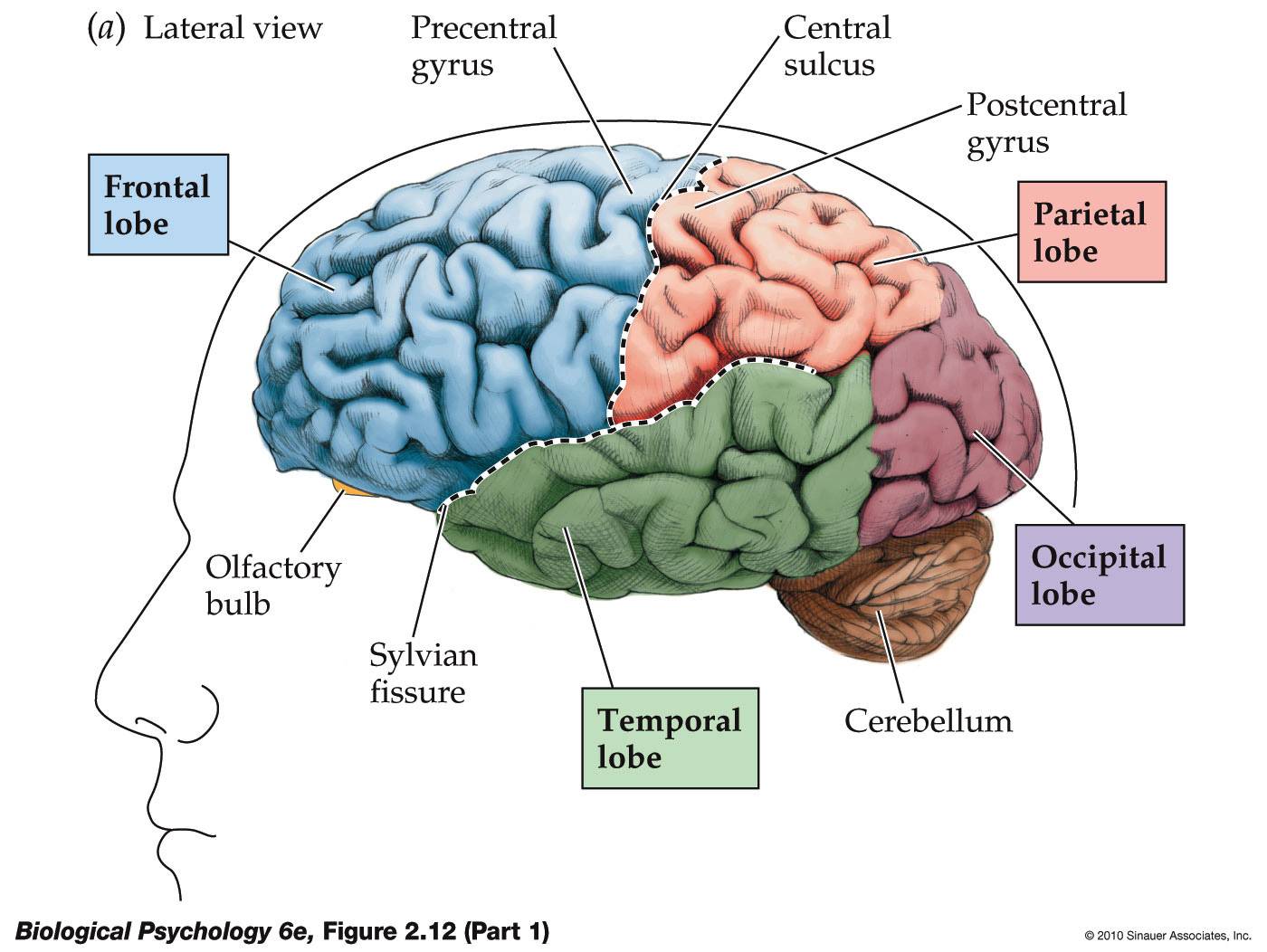

The ‘official’ line on the task is that it somehow taps into the function of the ‘hippocampus’ – a part of the brain near the ear, in the ‘temporal lobe’, so called because it looks like a sea horse (it is claimed) in brain sections. It’s a pretty robust finding since about the late 1970s that the hippocampus is one of the very first parts of the brain to be affected in Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s disease is THE most common type of dementia. It strictly speaking is a syndrome of different diseases of varying causes, but typically clinically is manifest as problems early on in learning and memory.

A good example of this, in fact, is in the film ‘Still Alice’, where the person who develops dementia notices early on navigating for a jog around a university campus familiar to her. And indeed it’s a fairly consistent finding that spatial memory, and learning lists of things and names can be difficult for someone relatively newly diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

This task has some validity from the animal literature. In rats swimming to submerged landmarks, the Morris water maze task, it’s well known that if you get rid of the hippocampus with physical destruction rats have real difficulty with this task.

Also, if you chemically manipulate the hippocampi of the rats’ brains with an agent which chemically blocks the way in which memory is laid down, known as ‘long term potentiation’, rats can’t do the task.

There are therefore different types of error – known as ‘between search’ and ‘within search’ errors.

Within-search errors were made if a participant returned to an already searched box; between-search errors occurred if a participant returned to a box that was already known to contain a target item.

There is a long and proud history of research into this, such as this paper.

The problem is – this is vastly to oversimplify the situation. If you extend the time window of the task, it no longer is a task of working memory, but more like a task of a ‘episodic’ memory for events. And the brain area really involved in spatial working memory has a large contribution from the frontal lobe, the part of the brain near the front. We know that this part of the brain tends to be affected later on in Alzheimer’s disease.

Still with me?

Well done.

There’s a problem also in the programmers’ use of the term ‘dementia’. Dementia is an umbrella term of well over 100 different conditions. Alzheimer’s disease is one of many conditions. But it is conceivable that other dementias may provide different patterns of behaviour on the task.

This is of course no bad thing – as ideally you should want to match up the different cognitive profiles of people playing the game with known diagnoses, such as likely normal ageing, or not.

But this is beyond the scope of the game. And a clear demarcation is made between playing the game for fun, and it NOT being used as a diagnosis of dementia.

But say you have problems in a different part of the brain, such as the parietal cortex. This part of the brain is involved in visual perception, so persons with the posterior cortical atrophy type of dementia might exhibit a different profile altogether.

And why this is relevant is all to do with how space is represented in the human brain.

Space which is allocentrically represented, i.e. objects in relation to each other, are more likely to be expressed in a cognitive map involving the hippocampus. On the other hand, space which is egocentrically related, i.e. related to YOU in space, is more likely to be involved in a map involving the parietal cortex.

As a summary of where these parts of the brain are, see this diagram.

So – it’s likely that behavioural performance on the task will involve performances from a hotchpotch of people, including some people with undiagnosed dementia. There’ll be some people who do badly on the task who don’t have dementia, so might be needlessly worried.

On the other hand, the game is brilliant for people to feel as if they’re participating research, without leaving the comfort of their own iPad or iPhone. And it’s great branding for the people involved in its creation and as a media campaigning tool.

I think the task itself is not a good computerised task. I worked in the lab which developed CANTAB in Cambridge under Prof Trevor Robbins, so there’s a bit of a conflict of interest. I found the music quite irritating actually, which is not fatal for motivation. But I think there is a major motivational confound in this task, where you can simply get bored of it the longer you play it for, affecting performance.

The lack of instructions was potentially a good thing – in that it minimised the confound of language problems affecting task performance. There are also some groups of patients who might be rather oversensitive or insensitive to rewards of any sort – such as people who are impulsive narcissistic at one end, or people who are profoundly depressed at the other end.

It’s also not a good pure test of memory either – there’s a huge perceptual component, evidenced by the great graphics. Also, there is a strong attentional component.

The attentional component is quite interesting though. In 1979, a paper in the Science journal first put the attentional part of the brain on the map, the so-called ‘cholinergic’ chemical system – which is why people are so interested in drugs such as donepezil today (donepezil is an example of a cholinesterase inhibitor.)

I think what would be interesting is if all the hundreds of thousands or millions of performances could be put into a giant database, and some sort of Big Data analysis could be run on it to see if different patterns of performance could be fractionated out. What would THEN be interesting for Dr Hugo Spiers and colleagues from UCL would be then to match up these profiles with known ‘diagnoses’, such as early Alzheimer’s disease, ageing, posterior cortical atrophy.

But this would be to get into the mire of ethical research, research approval and valid consent, perhaps?

I don’t wish to paralyse the greatness of this game by overanalysis. Go and download it, and help dementia research! Well done to the Alzheimer’s Research UK for an excellent collaboration which is very interesting indeed.