I have a foot in both research camps.

I believe in good quality research about the ‘medicine’ of dementia.

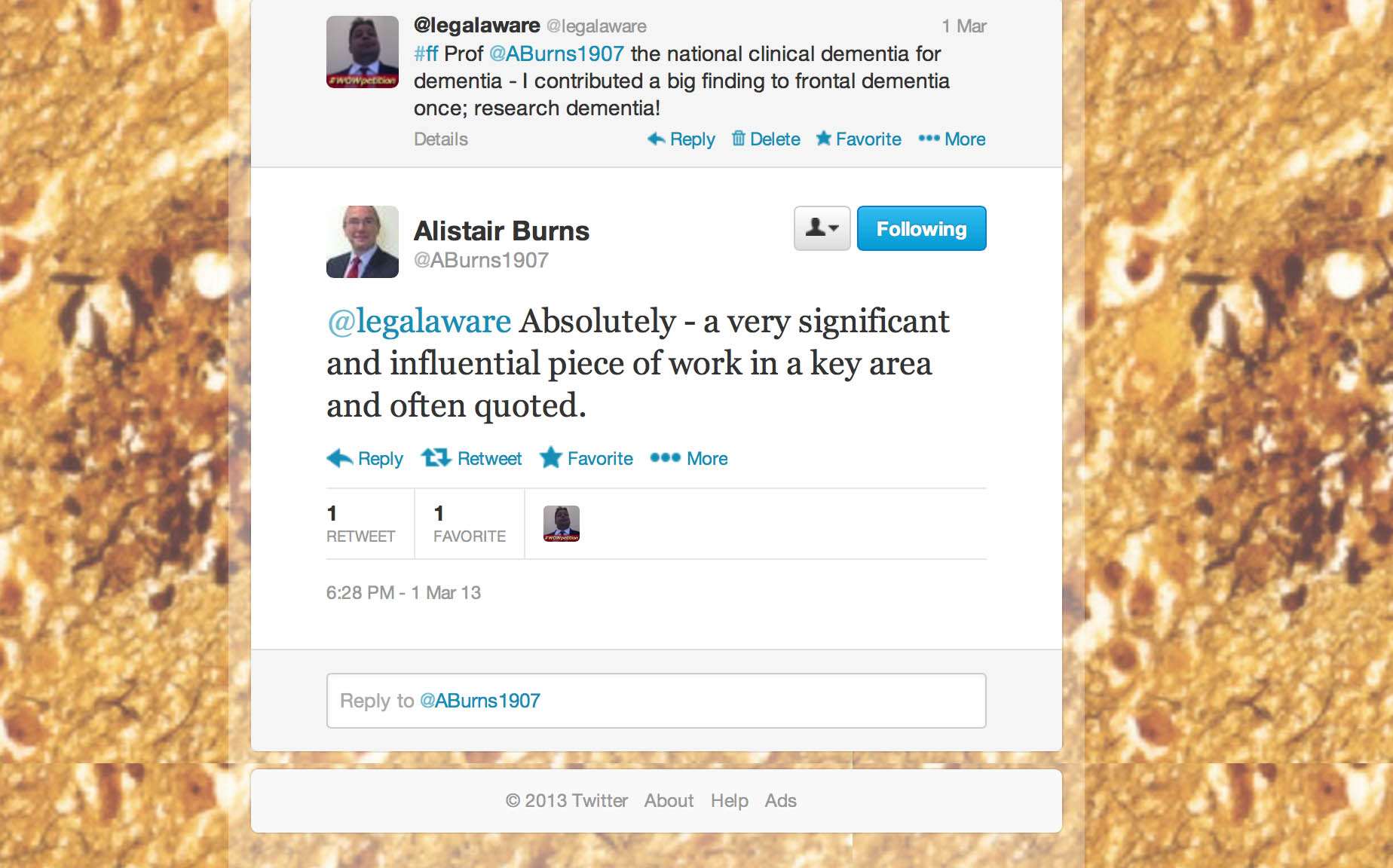

In the world of research, I am known to have contributed an original paper in the diagnosis of the frontal-variant of frontotemporal dementia.

This paper explained why people with a dementia could even end up having a diagnosis of this type of dementia, even though presenting in clinic with normal blood tests, psychological tests or brain scans.

Such patients did, however, have profound changes in behaviour and personality noticed by their closest ones, usually friends and family.

The paper itself has been quoted in the current Oxford Textbook of Medicine chapter reviewing the most common types of dementia, their diagnosis and management.

I do however have academic views on the importance of the ‘timely’ correct diagnosis of dementia, rather than early diagnosis.

I never give advice about anything on Twitter, as I am not a physician, but it is nice when what you say has an impact on general education of people about dementia.

I can be found on both @dementia_2014 and my other Twitter account (as I am trained in academic law as well as research in dementia) @legalaware.

Take for example how depression can be in the wrong hands misdiagnosed as dementia.

This is an example, perhaps, of where a diagnosis is a label, and disabling not enabling.

But for very many a correct diagnosis of a type of dementia will be a key to the door for opening up the relevant care.

I feel that, whatever the ‘fiscal constraints’ the NHS finds itself in now and the future, despite the argued need for transformational change in NHS services, people with dementia should be at some stage diagnosed by somebody with specialist medical experience.

This is reflected here in a recent excellent article in the Telegraph.

The other camp is this, and oddly enough there is some overlap in my wish for people with dementia to be given the highest priority in society.

I also firmly believe in good quality research of allowing people to live as best a life they can.

This is intensely personal, as I am physically disabled, and I am all too aware about how people can make crash judgments of you.

I am about to publish a book on ‘Living well with dementia’ on January 13th 2014.

I am honoured to be well respected by academics in the field of dementia, including Prof Alistair Burns the current lead for dementia in England.

I thrive from the research contributions daily all around the world in research into dementia.

I would like to see the UK play a part in leading the research community about all aspects, including the medicine of the condition itself, its possible cure one day, and current practical help in improving quality of life.

Finally, I think with the current academic community in the UK in dementia, the UK can and should achieve this.