A previous Government in 1997 launched a white paper consultation into the future of human rights legislation in England and Wales. This document called ‘Bringing rights home’ set out the then Government’s intention to bring onto the statute books a way in which parliament could make it straightforward for its citizens to bring human rights case, without petitioning Strasbourg directly. Access to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg was considered too costly and time-consuming.

Unless England and Wales stop being signatories to the Council of Europe, which is another component of uncertainty from the current administration, citizens in England and Wales will still be able to petition Strasbourg directly, as has been made clear for some time by their Lordships specialising in human rights.

Britain, under a previous Conservative government, had a major influence in drafting up the current European Convention of Human Rights. The rights themselves, such as a right to be free from torture or degrading treatment are pretty uncontroversial themselves. They are a huge factor in allowing citizens to hold their Governments to account. Under current legislation, the Human Rights Act 1998 in England and Wales gives citizens ‘rights’ against anyone carrying out a public sector function such as local authorities for breaches of human rights, and there are few sectors as important in this regard as health and social care.

“Dementia Rights” is a new initiative I have designed, which I intend to launch in Dementia Awareness Week. Dementia Rights, building on the success of “Dementia Friends”, sees dementia not from the perspective of someone who is ‘dementia friendly’ but from the person living with dementia and doubtless many other co-morbidities.

A right gives a person with dementia a license to do something, and these rights are currently legally enforceable through a number of routes. For example, the Equality and Human Rights Commission will see the occasional case of someone discriminated against on the grounds of living with dementia.

The logic is particularly relevant for someone living with a young onset dementia, that is a dementia which has shown itself before the age of 65. These tend to be dementias which are in the early presentations of some traditional late onset dementias, or late presentations of young adult or childhood conditions. They are not merely dementias which have been diagnosed early.

Such citizens tend to have young families or serious work commitments. They particularly need protection against unfair dismissal, that is dismissal for no good reason in no fair way, on the grounds of a disability. This is disability discrimination. The Equality Act (2010), which is not being abolished, indeed brought forward by a previous Labour government but in fact rooted in a consolidating act from previous Conservative instruments, defines dementia to be a disability. If it were to recognise formally a sustained cognitive impairment as a disability in keeping with their definition of a “disability” as “that which has a ‘substantial’ and ‘long-term’ negative effect on your ability to do normal daily activities” in this context, it would be much easier to bring cases to employment tribunals for people being sacked due to a sustained cognitive impairment.

If the ‘Dementia Rights’ initiative works, run by Dementia Rights Champions, it will help to embed a rights based consciousness in society. I do not intend to pitch it at any commissioners, though we do need to have some accurate measures of its benefit and outcomes. I intend rather to make it freely available as ‘open source’ in the best spirit of Paul Mason’s work on post-capitalism.

Launching in ‘Dementia Awareness Week’, I hope this will bring an added, a much needed further dimension, to living with dementia apart from future cures and other (predominantly reductionist biochemical) research, ‘dementia friendly communities’ and a social care system on its knees.

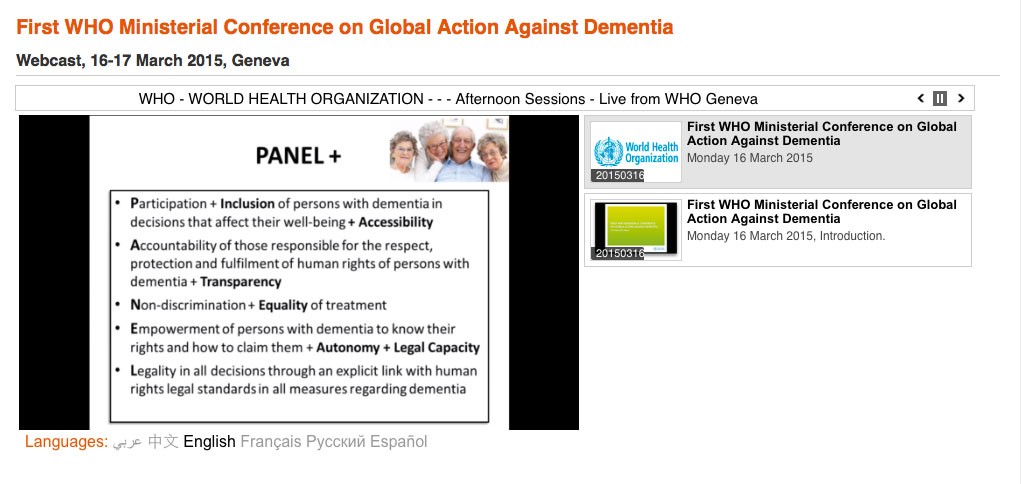

‘Dementia rights’ consists of a number of activities designed to encourage a discussion about the unique importance of rights for people with dementia, to emphasise five key messages: these messages are that rights apply to everyone and ought not to be taken away, rights go together with responsibilities, dementia is in law a disability, it is possible to enforce legal rights. and a major function of human rights law is to protect against discrimination.

I am grateful to all members of the public who have expressed an interest in this initiative of mine. I think none of this would have been possible had it not been for the groundbreaking work of Dementia Alliance International working in a strategic alliance with Alzheimer’s Disease International, in particularly the leadership shown by Glenn Rees and Kate Swaffer.

I am, in addition, particularly grateful to two members of the Queen’s Counsel, in the legal profession, who have shared the five key messages. Rights can be restricted in a legal away, but as soon as you deny rights unfairly, such as denying a right to complain, a right to a care home reflecting your sexuality, or a right to culturally appropriate diet, you are on a slippery slope.

The rights based approach is not supposed to replace the medical approach of diagnosis and cure, but I feel has substantially more to offer the rehabilitation and enablement approach pervasive from the social model of disability. A correct diagnosis of dementia should be helpful to all recipients of that diagnosis, not an encumbrance, and I feel promotion of dementia rights locally as well as internationally is now essential for this. Call it ‘Bringing dementia rights home’ at last.