All that glisters is not gold.

The progress in the English dementia policy jars inconveniently with the funding crisis and poor performance of some (not all) parts of the National Health Service.

The main issue is that the whole system is not working. For a start, it is not always possible to get people with dementia into hospital in a timely way as it is impossible to discharge ‘fit for discharge’ patients into the community due to the destruction of social care.

Earlier this year, we were also greeted by this cheerful headline:

And we know that social care has been on its knees for some time.

Richard Humphries, hugely respected at the King’s Fund, gave this unequivocal appraisal in December 2015 concerning the smoke and mirrors of the social care settlement, clouded by talk of the ‘precept':

“Instead of a fundamental root and branch review of how entitlements, as well as funding, are aligned across the NHS and social care, as proposed by the Barker commission, the government has chosen an opaque and messy hotchpotch of measures, which fails to address the short term pressures on social care; it does nothing to place funding on a more sustainable footing in the longer term.”

Dementia policy is currently running in two parallel universes. One universe is the poor state public health and social care find themselves in. The other is the multi-million pound ‘transformation fund’ for drugs for dementia, which may even be too expensive for the NHS to offer in a comprehensive way.

So what’s new in dementia that the Prime Minister can possibly get his teeth into?

The think tank Reform wrote some time ago their perspective about the situation:

Nick Seddon used to be the Deputy Director of ‘Reform’.

He wrote in the Telegraph back in 2010, just as the intense political debate over the much criticised Health and Social Care Bill erupted, the following:

And the solution, unsurprisingly, is framed in terms of a hybrid insurance model.

Lord Warner was the only Labour Peer to vote in favour of the Health and Social Care Act (2012).

And, of course, there was the ideological legacy from the New Labour era, exacerbated a million times worse in the Health and Social Care Act (2012) due to the introduction of default competitive tendering under s.75, of competition as a tool to improve quality. There is very limited evidence to support this, whereas there is quite substantial evidence to show that competition in health markets worsens health equity, and is very costly.

In the Guardian in 2014, a description was given of his new Jerusalem on the NHS based on co-payments and an emphasis on prevention.

So fast forward to the current framework of the NHS underlying the ‘vanguards’ and the ‘new models of care’.

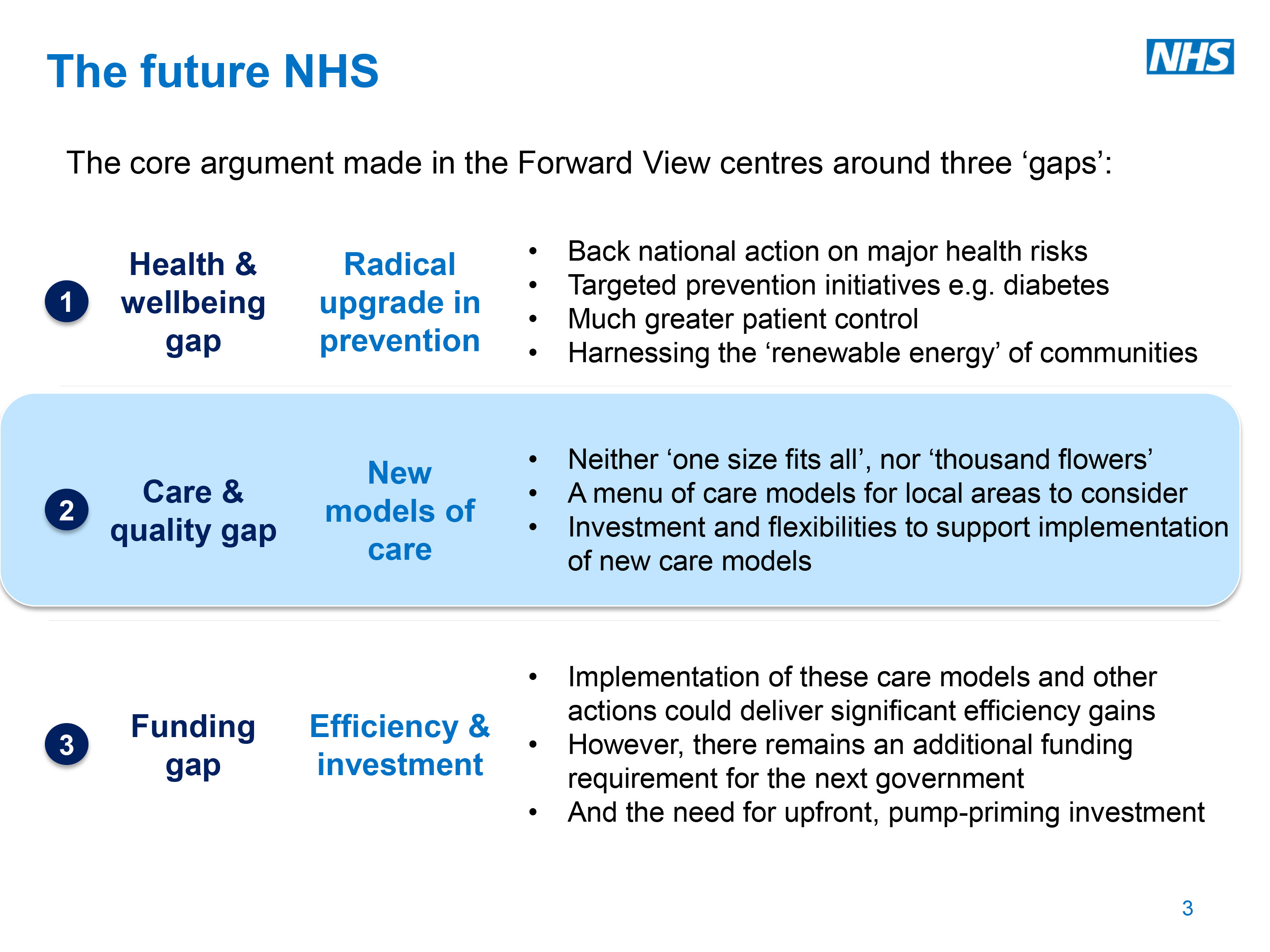

This all cosily fits in the structure of the ‘three gaps’ of the ‘Five Year Forward View’ from Simon Stevens, whose new Labour background is well known. In 1997 he was appointed policy adviser to two Secretaries of State for Health (Frank Dobson and Alan Milburn) and from 2001 to 2004 was health policy adviser to Tony Blair. He was closely associated with the development of the NHS Plan 2000.

Closing the ‘prevention gap’ is still “big business”. There has been an increasingly tendency to pedal the ‘we’re all patients now’ meme with the Big Charity creations of ‘pre-dementia’ and ‘pre-diabetes’, for example. Reasonable clinicians are of course running a mile from this. And – guess what – prevention of dementia means big money.

However, res ipsa loquitur.

There is one huge reason why the mechanism of us pooling risk together through general taxation is the best way to look towards the future of dementia care. The alternative, through private insurance, would be an unmitigated catastrophe. But this is an ideological war against the National Health Service, and various devices such as the insidious introduction of the personalised budget through the Care Act (2014) have seen this subtle rationing of resources to the individual level, under the deceptive marketing of the word ‘choice’.

It is no accident that Simon Stevens is a huge fan of genomic medicine. With the possibility of your entire genome being scanned, for risk factors for dementia, you could be aware of your risk for dementia and be inclined then to take out private insurance. But the research into genetics in dementia is advancing quite rightly, as it is hoped that efficacious interventions for a suitable subset of genetic +ve persons might exist in the future.

But Alison Cameron has described very elegantly, recently in “Healthcare Manager” magazine, how the patient movement views itself as more than data points as a bit part for others’ agendas.

This creation of new private markets is the ultimate nirvana of those propose privatisation.

But it is a hugely slippery slope.

You could find out you’re at high risk of dementia and decide you’ve got nothing to lose, as the insurance company will pay out, and blow your lifestyle on all the unhealthy risk factors. Or if you’re at low risk you could decide that paying into the NHS is not for you, and opt out for a relatively cheaper private insurance system.

In 2008, in the US the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (“GINA”) was passed into US law, prohibiting discrimination in the workplace and by health insurance issuers. One wonders whether a genetic phenotype should be considered one day for an amendment in the Equality Act for overseeing such claims under discrimination law.

GINA prohibits issuers of health insurance from discrimination on the basis of the genetic information of enrollees. Specifically, health insurance issuers may not use genetic information to make eligibility, coverage, underwriting or premium-setting decisions.

What has genetic discrimination in the US looked like?

Pretty ugly, as for example this:

“Jacob, a boy who carries a gene for a disorder called Long QT Syndrome (LQTS), was denied coverage under his father’s health insurance policy because of his pre-existing condition. LQTS is a rare and little-known genetic disorder that sometimes triggers sudden cardiac death. Those who carry the gene may be healthy until they suffer an attack without warning, but carriers can control their risk of cardiac arrest with preventive beta-blocker therapy. Jacob’s father wanted Jacob to be insured, but even after their state enacted a law prohibiting genetic discrimination, Jacob’s insurance company still refused to cover him.”

Wendy Mitchell, living with dementia, was asked at a recent dementia ’round table’ at the Department of Health:

‘How are things changing on the ground?’

The answer is: probably not as fast as they’re going in Whitehall.

The new question is: “Are you ready for this?”