Chris Roberts, living with mixed vascular and Alzheimer’s dementia, stated clearly in a session run by Angela Rippon at the Alzheimer’s Show: “It’s not only awareness we need: it’s actual education”

He was of course referring to the mushrooming of ‘dementia awareness’.

At one level, “awareness” is very basic. It’s called “tier 1″ in the jargon, as the ‘entry level’ for how services for dementia could be organised.

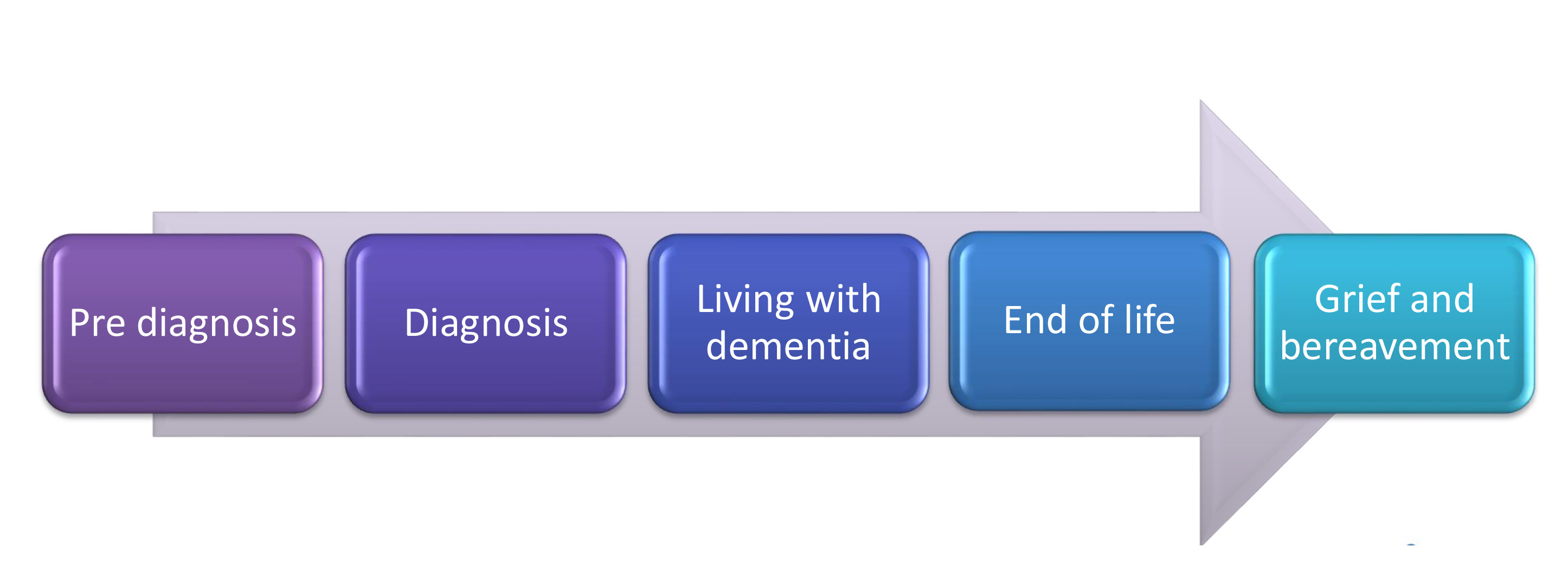

Ceri Hodgkison and Dr Karen Harrison Dening in a talk at the Royal College of Nursing explained how dementia care lies on a continuum at the Royal College of Nursing the other week.

A concerted effort must now be made into why many people find the actual disclosure process of the diagnosis of dementia very unsatisfactory. This must aim at looking at why the beliefs, concerns and expectations of the imparting of that information fell below standard, sometimes, and there must be mechanisms for acting on that at an individual basis.

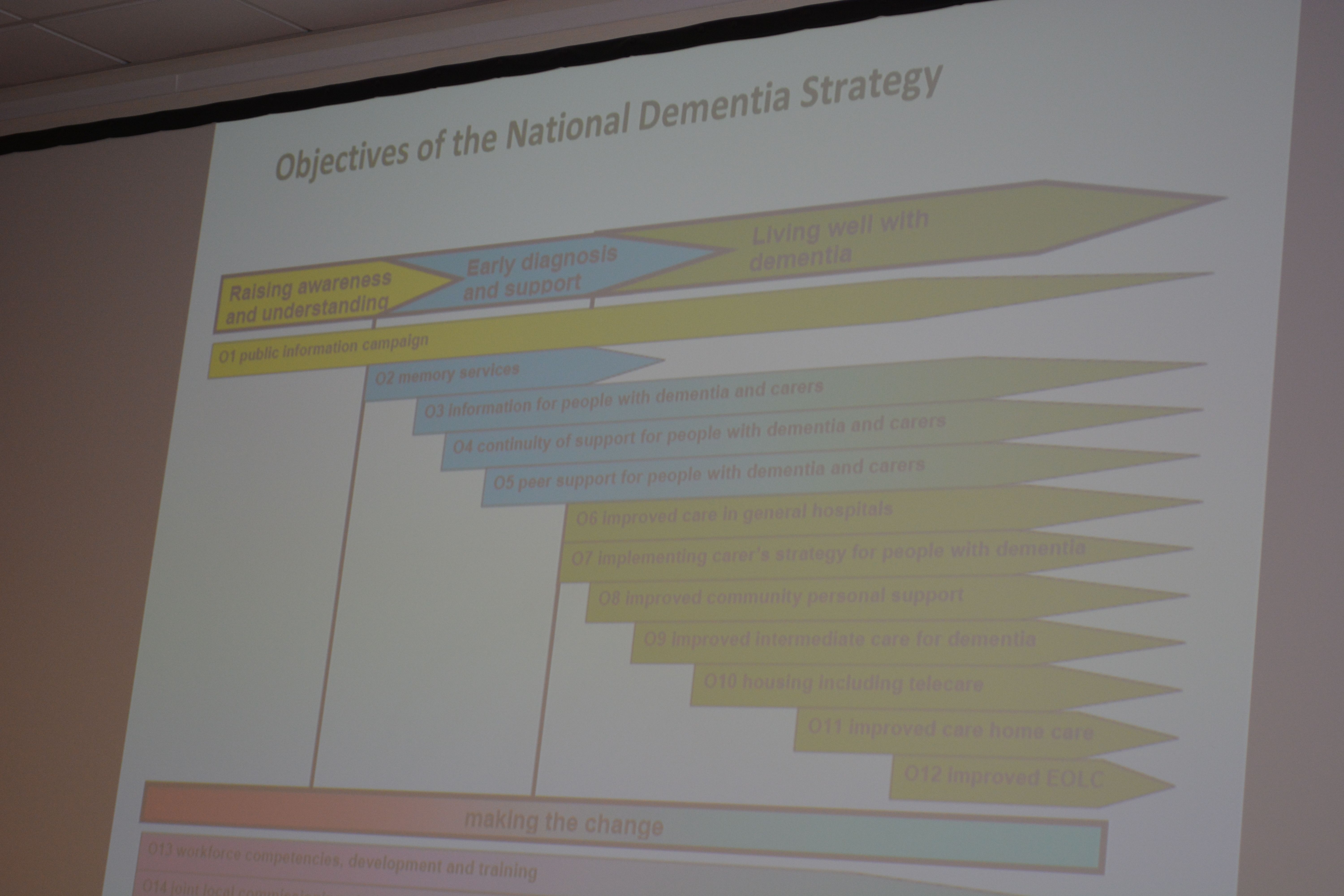

The English nursing strategy provides for a diversity of nurses involved in care: ranging from “dementia aware” to “dementia knowledgeable” to “dementia specialist”.

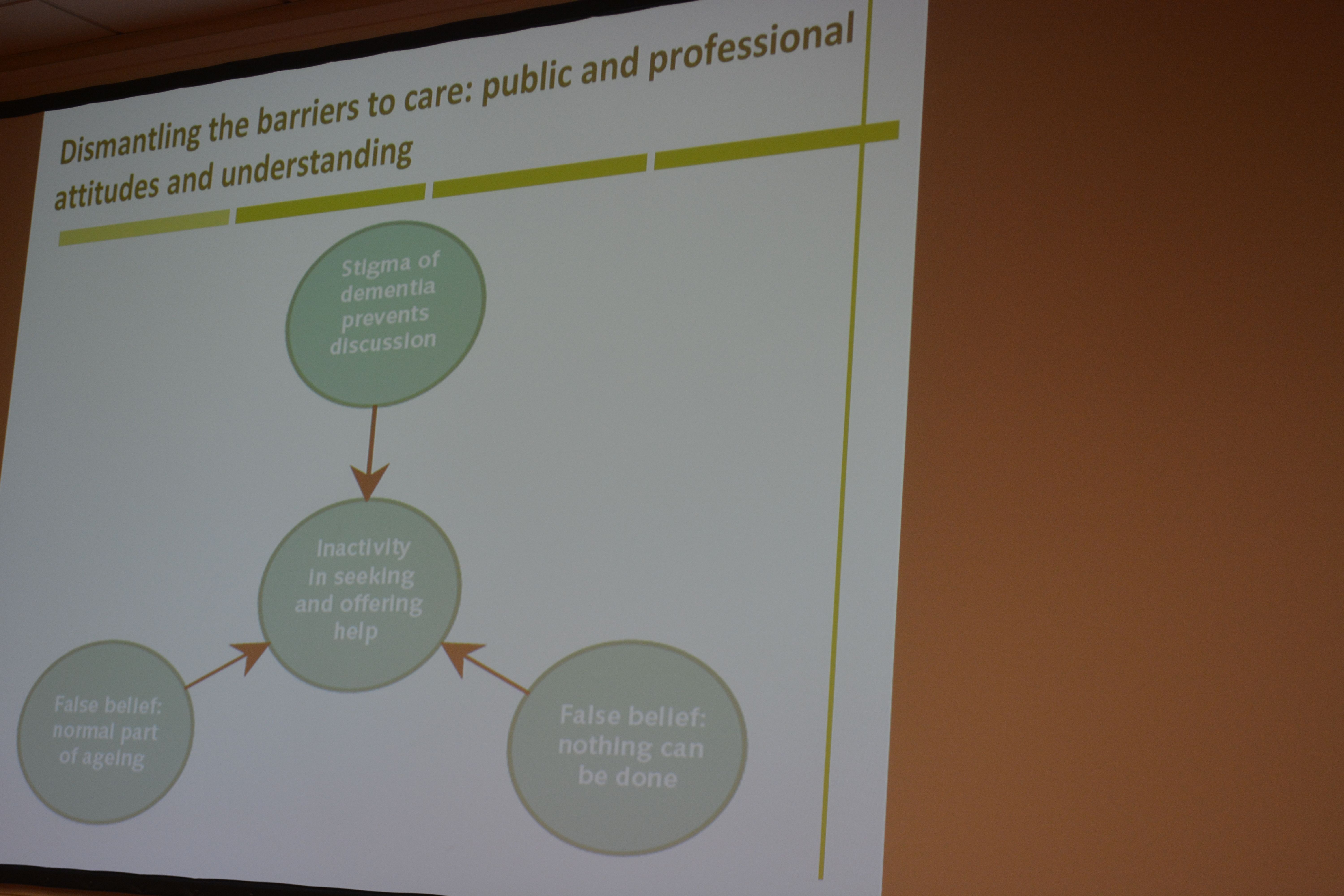

There has been a drive to denegrate specialist knowledge, in a general drive towards ‘generalists’, but I feel strongly there is a place for all contributions. Simply, awareness is not enough.

The complexity of dementia service provision in part comes from the unique way in which the brain can be affected in the hundred or so different types of dementia. Dementia, however, I would humbly submit poses considerations of its own. It directly affects how the person communicates with the world, and this can potentially alter the dynamics and perception of that person.

It also poses clinical issues for the National Health Service and social services. A person living with dementia as such is unlikely to present to the NHS with ‘an acute exacerbation of dementia’, though in one sense might do such as repeated falls. A person living with dementia as the condition progresses is likely to accumulate an increasing number of other clinical diagnoses which need addressing; they may affect the decision for transition into a residential care setting.

A person living with dementia may enter an acute hospital setting from one of many other care settings; such as CMHTs, hospices, care homes, nursing homes, or even directly at home (if the emphasis has been on ‘self care’).

A member of the family will often find himself or herself as a pivotal person involved in the care and/or support of a person with dementia. He or she can know things other people will not know.

So when a person living with dementia enters a care setting, there is a fundamental change in dynamics which happens. Often a member of the family, thus far in a caring role, finds the care being transferred to relative strangers. But there, in fact, remains a ‘threesome’ – the person with dementia, carer, and member of staff (such as nurse, allied health professional, etc.)

In a paper published in Dementia journal in 2014 from the School of Nursing and Midwifery at Monash University, Australia, the authors looked systematically at the experience of family caregivers of people with dementia who were admitted to hospital.

People who are ‘family caregivers’ clearly have substantially more than an ‘awareness’ of dementia. They are in effect ‘experts’ of care, who take their responsibilities of care extremely seriously. They can have substantial care and support needs of themselves.

One sentence in this paper really caught my attention.

“Carers often have a negative experience with hospital care (Jurgens et al., 2012) and can feel overwhelmed and under-noticed by the system and the teams of clinicians who work within it (Haesler, Bauer, & Nay, 2007).”

And yet this the very opposite of the ‘triangle of care’ proposed in a strong contribution by the Carers Trust/Royal College of Nursing.

This is a massive deal: as people very close to a person living with dementia find themselves rapidly acquiring ‘visitor status’, in an institution, according to the authors.

And the emotions can be huge in being asked to respond to their experiences.

“One participant said that it was a relief to be able to talk confidentially about her feelings to someone external and that ‘Noone had asked her how she felt before ’. Another who was crying intermittently throughout the interview was asked by the researcher whether she would prefer to stop the discussion. She responded ‘No, it’s a relief to get this all off my chest ’.”

It is arguably a case of ‘common sense and compassion’ to allow friends and family as company for people living with dementia during the course of a ‘hospital stay’; and John’s Campaign has made huge progress with this, not least pursuant to monumental leadership by Nicci Gerrard.

We need also high quality research, rather than marketing, into the ability of stories from caregivers and people with dementia who feel able to provide such narratives to shape local acute services in dementia.

Sometimes it feels as if ‘the world is not enough'; but, as start, awareness is not enough.