OK it’s not heaven on earth – but Kentish Town London does have some merits I suppose.

To say that I am passionate about the dementia policy in England is an understatement.

Throwing forward, I believe living well with dementia is a crucial policy plank (here’s my article in ‘ETHOS journal’), for which service provision needs a turbo boost through innovation (here’s my article co-written in Health Services Journal).

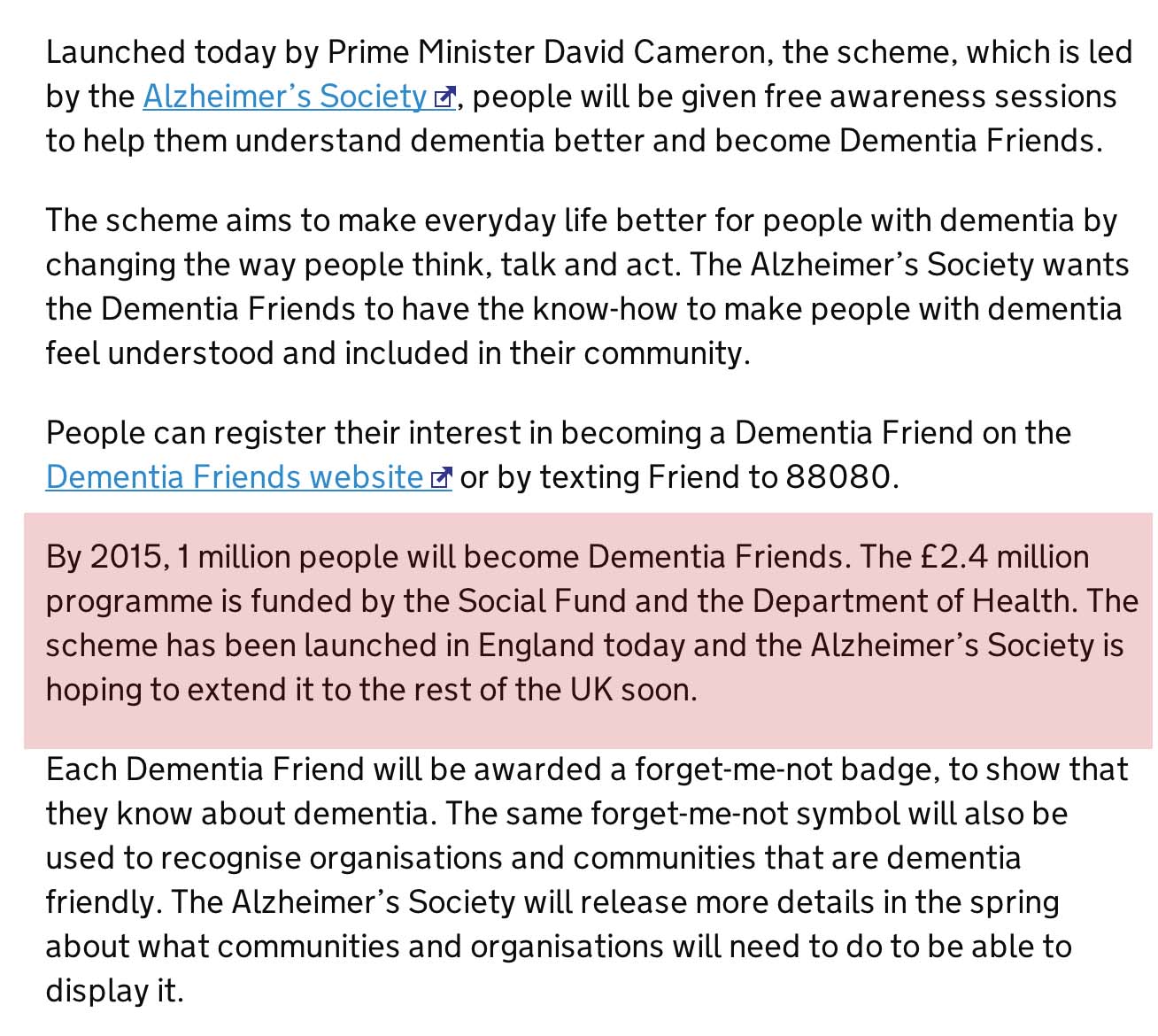

“Dementia Friends” in reality means rocking up in a venue somewhere near you for about 45 minutes to learn something about the dementias.

Once you sign up on their website, the experience is also backed up by an useful non-public website containing details of training, pre-training materials, and help on how to promote sessions. You can also provide on that website precise details of any ‘Dementia Friends’ information sessions that you run in due course.

I had known of this initiative mainly through Twitter, where I am very active. I find the twitter thread of @DementiaFriends interesting.

Even I’ve been known to get involved in a bit of mass hysteria myself:

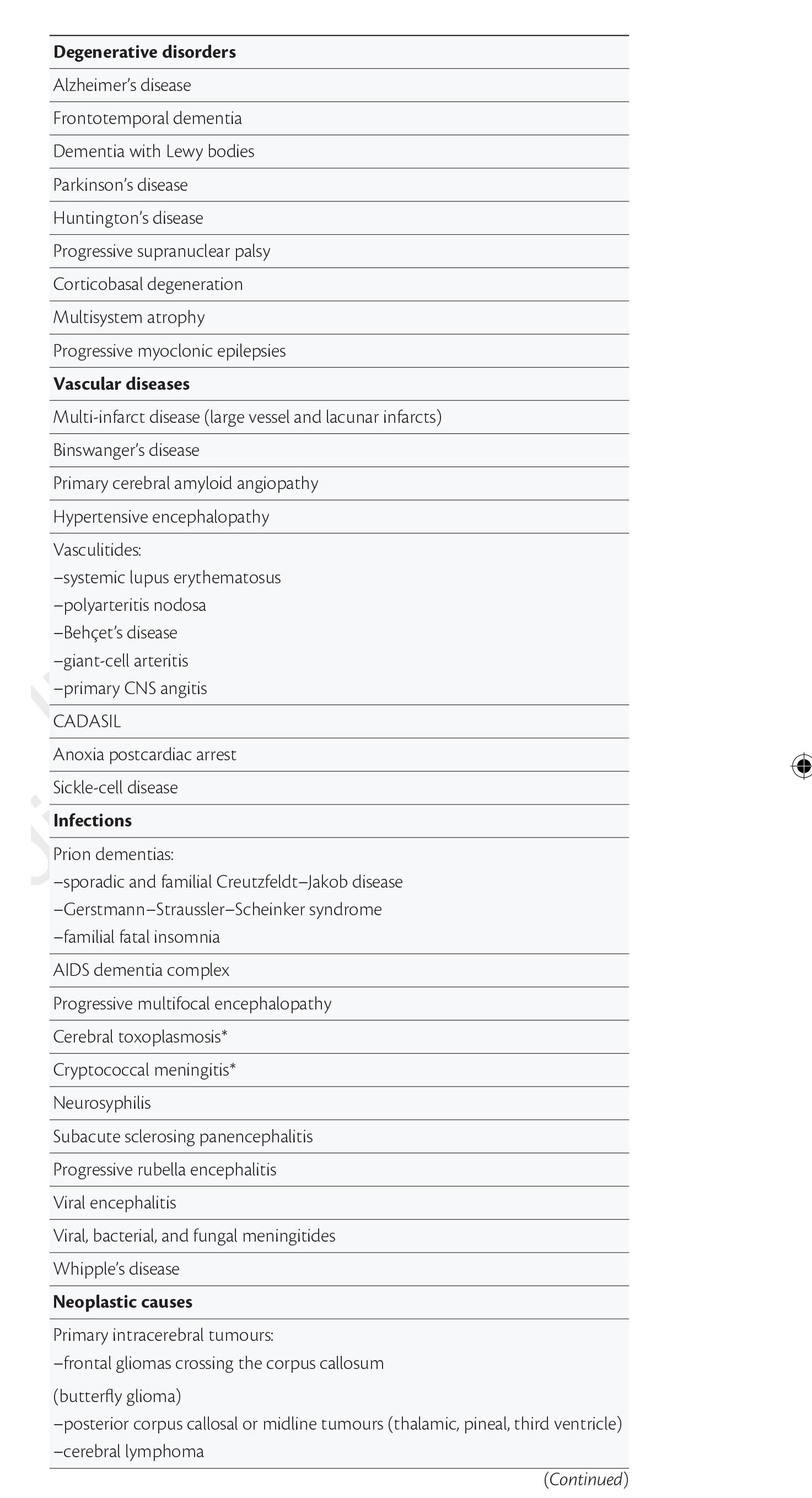

I possibly signed up despite of the substantial interest in the media and social media, what psychoanalysts might call an “abreaction”. There’s a large part of me which feels that I do not need 45 minutes on dementia, having studied it for my much of my final undergraduate year at Cambridge, done my Ph.D., written papers such as this (one of which even appears in the current chapter on dementia in the Oxford Textbook of Medicine), written book chapters on it (which as this one which appears in a well known book on younger onset dementia), and even written a book on living well with dementia.

But Prof Alistair Burns is a Dementia Friend – and he’s the clinical lead for dementia in England.

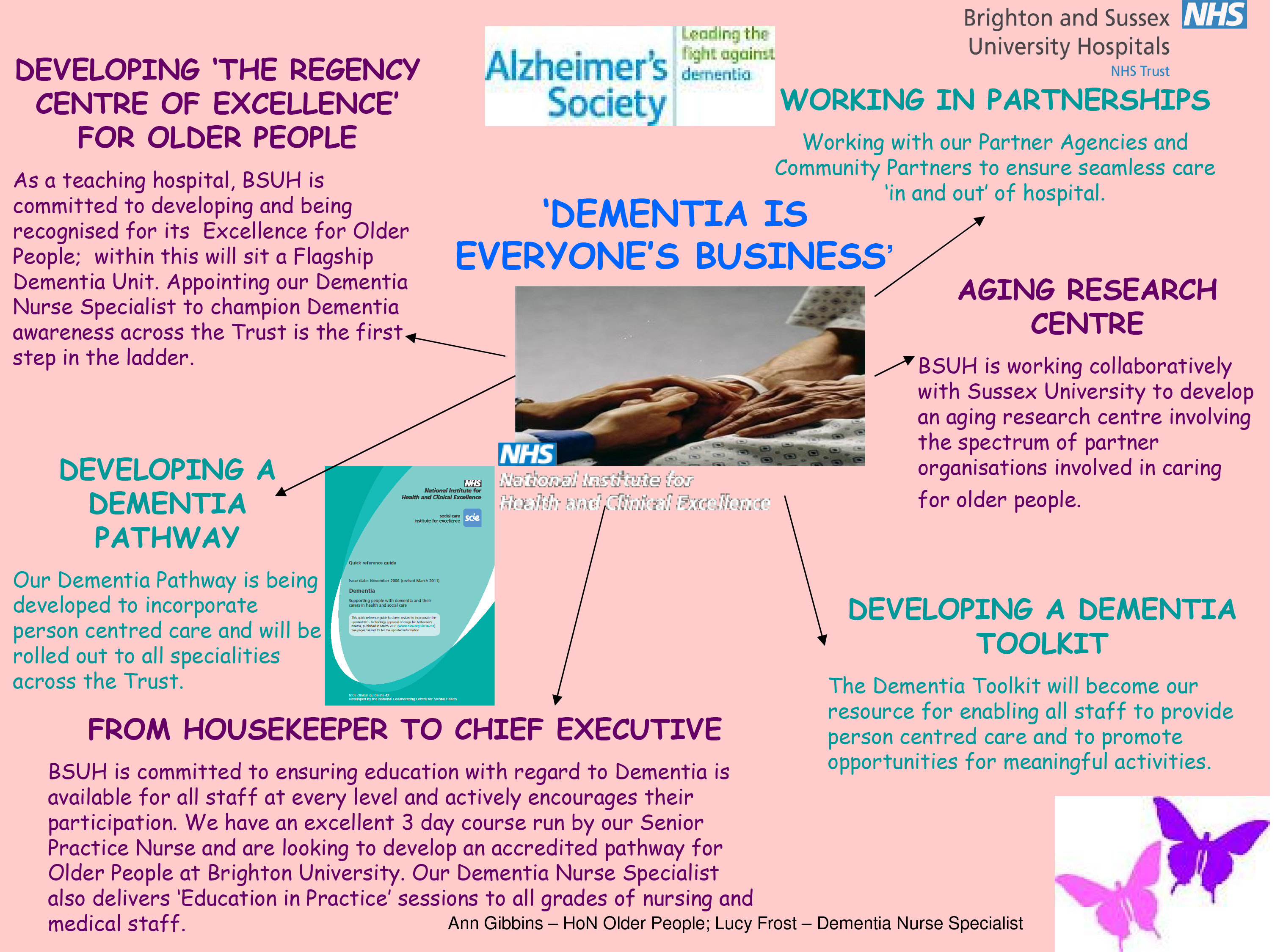

I went out of curiosity to see how Public Health England had joined forces with the Alzheimer’s Society. I must admit that I am intensely loyal to the whole third sector for dementias, including other charities such as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Young Dementia UK, Alzheimer’s BRACE, and Dementia UK.

I have my own particular agendas, such as a proper care system for England, with the provision of specialist nurses such as Admiral Nurses. I think some of the English policy is intensely complicated, best reserved for those who know what they’re talking about – especially people currently living with dementia and all carers including unpaid caregivers.

I personally think the name ‘dementia friendly communities‘ is ill conceived, but the ethos of having inclusive communities, well designed environments and ways of making life easier for people with certain thinking problems (such as memory aids, good signage) highly attractive. It would be unfair in my view for this construct to be engulfed in cynicism, when the fundamental idea is likely to be a meritorious one.

But I don’t think Dementia Friends competes with any of that, and one must be mindful of the gap society had of awareness of dementia.

This gap is still enormous.

And the aim is for people – not just Pharma – to be interested in dementia. These are real people with their own lives, not merely ‘potential subjects for drug trials’ (worthy that the cause of finding an effective symptomatic treatment or even cure might be potentially). But these are people living in the now – take for example the Dementia Alliance International, persons with dementia with beliefs, concerns and expectations of their own like the rest of us.

Only at London Olympia at the “Alzheimer’s Show” [and it is very well I am not a fan of such events which I have previously called “trade shows”], the other week, I presented at London Olympia for my ‘Meet the author session’, arranged on the kind invitation of various people to whom I remain very grateful.

At “The Alzheimer’s Show”, I met within the space of ten minutes a lady newly diagnosed with vascular dementia who did not intend to tell anyone of her diagnosis, and one person married to someone with probable dementia of the Alzheimer type who did not even tell his friends for three years.

It’s a rather badly articulated slogan but the saying ‘no decision made about me without me’ I think is particularly important for dementia.

These are two real (without warning) discussion points from the floor.

“Are people with dementia actually involved with any of the sessions?”

Yes: in fact my pal Chris Roberts (@mason4233) in Wales delivers his Dementia Friends sessions word-perfect for 45 minutes, without telling his audience that he himself lives well with dementia until the very end. Chris tells me this dispels, visibly, preconceived prejudices from his audience members. Chris blogs regularly on his blog, and has written for the ‘Dementia Friends’ blog.

“Why should people with dementia be given special elevated status compared to any other medical condition?”

It’s a difficult one. Some people believe that with dementias people will easily ‘snap out of it’ ‘if they pull themselves together’. This is completely at odds with one of the learning points that dementia is chronic and progressive. And of course people in the real world – viz CCG commissioners – have to decide how much they wish to prioritise dementia ahead of, instead of, etc. other medical conditions such as schizophrenia. But people living with dementia can present with known problems such as forgetting their pin number, and therefore it’s not actually a case about giving people with dementia an ‘elevated status’, but getting them up as individuals to be expected from anyone. Although it’s motherhood and apple pie, it’s very difficult to find, whatever the motive, the intention of dementia friendly high street banking fundamentally objectionable.

Dementia Friends Champions become rehearsed in the programme at one-day sessions across England. What happens is that you watch videos on their website, sign up for a day (where you get to take part in a Dementia Friends session) and then attend the session somewhere close to where you live habitually.

The sessions are run all over England at regular frequency. You sign up for a session, then you get an email quickly afterwards. You go to the meeting.

My meeting started on time. I am physically disabled, so I was grateful for easy access to the venue in Voluntary Action Camden (I could use the lift).

One of the things some of us mean-minded people pick holes in is whether the venue itself might be dementia-friendly. TICK.

I thought so.

The group dynamics worked really well.

My group consisted of interesting people, all ‘realistic’ in their expectations of shifting the Titanic of messaging of negative memes in the media. Many of my group were particularly interested in social equity, fairness and justice, reading between the lines.

I particularly enjoyed speaking with one delegate who is a NHS consultant in psychiatry. We went through pleasant niceties of what he was examined on in his professional membership exams (in his case the difference between schizophrenia and drug-induced psychosis). But he was great to chat to during the day.

I bored him to death with my example of persons with dementia putting numerous teaspoons of sugar in their cups of tea, on rare occasions, due to ‘utilisation behaviour’, a particular predilection for sweet foods since the onset of dementia, or cognitive estimates problem, a very niche area of cognitive neuropsychology for both of us. But this was simply in an activity on making tea where such private chit-chat was irrelevant; the actual session as delivered, on how to make a cup of tea, was far superior than the two hour version I did in a workshop for my MBA in that well known method known to managers: “process mapping“.

The whole day was presented by Hannah Piekarski (@HannahPiekarski), Regional Volunteering Support Officer for the London and South East region for “Dementia Friends.

I’ve sat through more presentations than you’ve had hot dinners, but the standard of the presentation was excellent. Although the presenter clearly had a corpus of statements to make, the presentation was not contrived at all, and the audience had plenty of opportunity to ask questions at points during the day. The presenter evidently knew what she was doing, and was a very good representative of the Dementia Friends programme. She gave her own ‘Dementia Friends’ session which the group of about twenty found faultless.

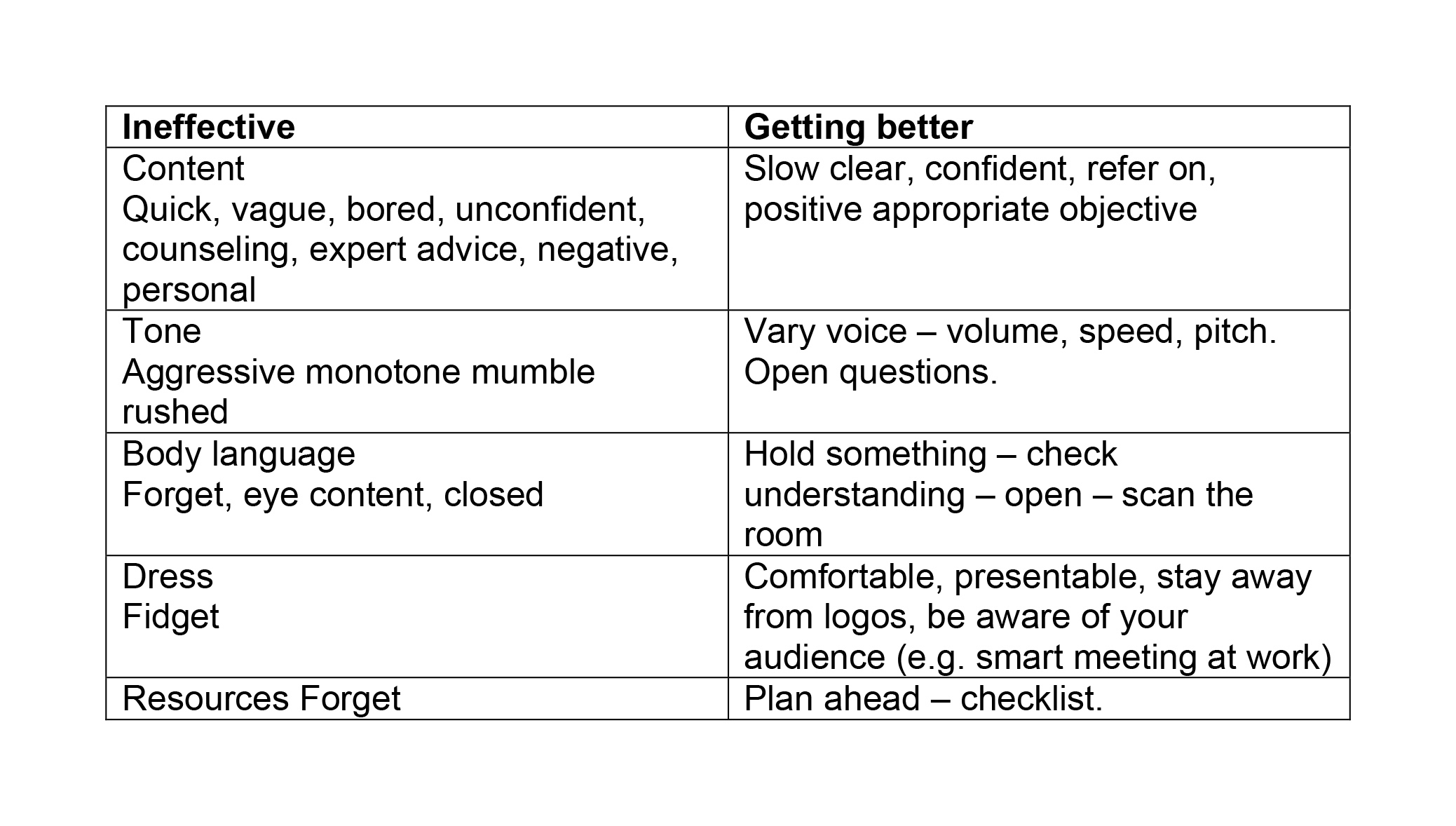

Hannah even ran a session after the lunch break on what makes a BAD presentation.

Here are my scrappy notes which I took – and please don’t take this to be representative of the actual discussion of what makes a bad presentation which we had in our group.

I SO wish some of my lecturers (including Readers and Professors) had been to Hannah’s session on generic skills in presentations. Whatever you do after ‘Dementia Friends Champions’ day, there’s no doubt that such a session is really useful across various sectors including law and medicine.

You don’t really have to take notes as it’s all fundamentally in their well laid out handbook.

The day was run with the purpose of not giving you tedious crap on how to run a session. But it was furnished with many useful pointers. For example, I learnt of possible venues such as a local library, church halls, and community centres.

Actually, I have in mind to ask Shahban Aziz, CEO of BPP Students, Prof Peter Crisp (Professor of Law at BPP Law School) and Prof Carl Lygo (also Professor of Law at BPP Law School) whether I might run dementia friend sessions at this law school which I attended for my pre-solicitor training. I’ve always had a bit of a discomfort that lawyers are not really given any introduction to dealing with people with dementia, other than professional regulatory considerations or in direct dealings with the law such as mental capacity? I think it’d be great if law students had a basic working knowledge of what dementias are.

It was nice for me to get out of my flat, and meet a range of people. These people ranged from other people in the third sector, for example the Dementia Action Alliance. They bothered to provide free coffee all day, and a free lunch.

And when I tweeted that on my @legalaware Twitter account from my mobile phone in the lunch break (you’re told to turn your mobiles off for the day), I received this smartarse (#lol) remark from one of my 12000 followers immediately.

You’re given a guidebook. You’re not coerced in any way into becoming a Dementia Friend or Dementia Friend Champion. You’re told specifically having done Dementia Friends you can do whatever point of action you wish, even if that includes supporting another charity other than the Alzheimer’s Society.

You are told that the point of the current dementia strategy in England in no way is intended to be political. In support of that claim is that the current strategy has overwhelming cross-party support.

The sessions include information about dementia and how it affects people, as well as the practical things that can be done to help people with dementia live well in their community.

I was given resources to answer people’s questions about dementia and suggest sources of further information and support.

After completing the course Dementia Friends Champions can access resources and tools to help set up and run sessions for people who sign up as Dementia Friends.

These resources include exercises, quiz sheets, bingo sheets, book club ideas and reading suggestions. You’re made very familiar with the content of ‘Dementia Friends’ as they helpfully provide ALL the material on the website when you sign up. They don’t hold any of it back. The point is you go away and run the whole session as ‘Dementia Friends’. Having seen how the 45 minutes works, I have no burning desire to change any of it.

Having said that, there are one or two things I would do differently, hypothetically. The format makes it very clear the presenter is not an expert in dementia or counsellor. I think this actually helps in that an expert possibly could write an hour long essay on each of the five statements for finals, and get truly bogged down in “paralysis by analysis”.

One of the possible features of the ‘Dementia Friends’ session is comparing dementia to a bookcase. This is a well described metaphor, first proposed by Gemma Jones. I have indeed used it to propose a scheme of explaining ‘sporting memories’, an initiative which recently won the Alzheimer’s Society Dementia Friendly Communities national initiatives awards.

Here’s my pal Tony Jameson-Allen picking up his gong.

There’s a bit in the explanation of the bookcase analogy that gets quite technical in fact.

With the presenter of the session having said that he or she is not an expert in dementia or counsellor, it seems counter-intuitive to me that there is an explanation of the organisation of memory using two highly technical locations in the brain, the hippocampus and amygdala. But things like that are not a ‘deal maker’ or ‘deal breaker’ for me. There’s an excellent video of a presentation of the bookcase analogy by Natalie Rodriguez floating around, in fact, but we were all encouraged to be explain the analogy ‘live’ in our sessions, ‘rather than playing the DVD’.

I have absolutely no problem with the material being pre-scripted. I used to supervise neuroscience and experimental psychology for various colleges at Cambridge between 1997 and 2000 inclusive, and, whilst the guidance for teaching that was not as intense, it’s fair for me to mention that supervisors knew exactly what they had to cover for their students to achieve at least an upper second in finals.

Dementia Friends Champions, like me, are then be encouraged to run Dementia Friends sessions at lunch clubs, educational institutions and other community groups, but it could also include ideas such as arranging a meeting to talk with a small group of friends.

I intend to run five sessions to achieve about 100 further dementia friends. I conceptually find targets anywhere quite odious, and see exactly where this ambition has come from (Japan). On the other hand, nobody is a clairvoyant. The fact the number exists at all (aiming for March 2015) is a testament that this programme is being taken seriously. Had the number been set at 400, then we would all have said ‘job done’ some time ago.

I am actually, rather, amazed that somebody somewhere has signed off for a national programme to invite ordinary members of the public to attend free of charge a day on delivering the Dementia Friends programme, with nice company, and of course that free coffee and lunch.

I am also amazed that the actual substrate of the information sessions for ‘Dementia Friends’ is being offered to the member of the public free of charge, and it effectively has been paid for by Government.

The operational delivery of ‘Dementia Friends Champions’ day was totally faultless from start to finish. Even though I have nothing to do with their output, the Alzheimer’s Society here in England have done a brilliant job with it.

And finally I’ve tended to query whether it can be a genuine ‘social movement’ which so much resource allocation.

But people are genuinely interested in the programme, as these tweets to me demonstrate, I feel:

Look.

In a different jurisdiction – Australia – a close friend of mine, Kate Swaffer (@KateSwaffer), blogs daily on her busy life living with dementia, which includes being an advocate, travelling, cuisine (Kate is very experienced in sophisticated cooking), a background in healthcare, a student at the University of Wollongong, and what’s it like to live with dementia after being given the diagnosis. Her blog is here.

Chris, Norrms and Kate are all quite different – like the rest of the population – getting on with their lives. And as the very famous adage goes, once you’ve met one person living with dementia, you’ve done exactly done. You’ve met only one person with dementia.

And there’s clearly a huge amount to be done. Also at the Alzheimer Show one carer reported a person with dementia being ‘lost to the system’, completely unknown to anyone for care for three years.

I had a huge volume of concerns about this initiative, and I’m no pushover as far as being ‘in with the in-gang’ is concerned. But I strongly recommend you park your misgivings and go there wanting to be a part of a “change”.

I went on the day after the passing away of the incredible Dr Maya Angelou.

As she said, “If you don’t like something, change it. If you can’t change it, change your attitude.”