All governments in the UK have recently thought about ‘reforming public services’, mostly in the context of public-private partnerships (PPP) or the private finance initiative (PFI). Third sector organisations, such as social enterprises and charities, especially large ones, are acting in increasingly private or even corporate ways.

Many feel that this has now become a dangerous policy issue in dementia in England.

There is much goodwill towards dementia as a cause, not least because there are 800,000 people living with dementia currently in the UK. On account of this, there should be a moral onus for fundraisers and politicians to act in the general interests of all people with dementia, and carers.

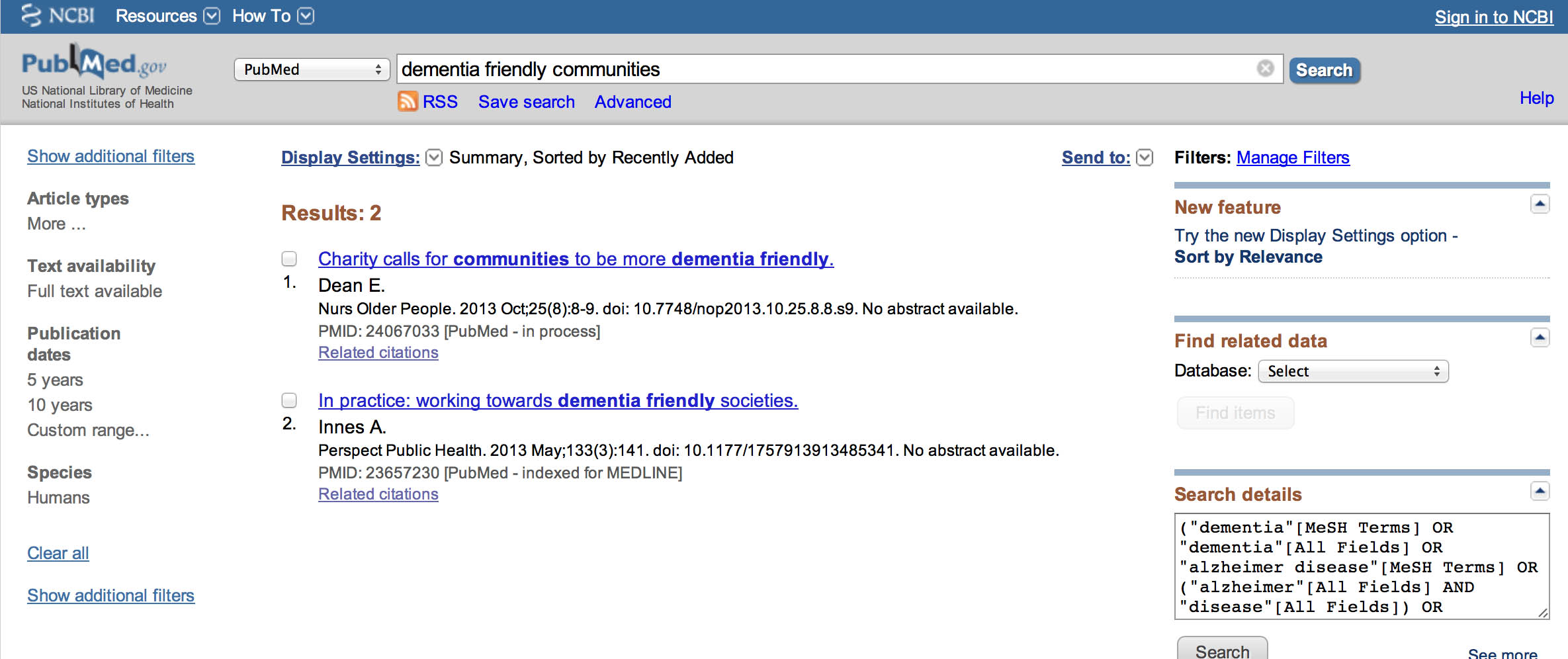

Take for example the report of the “Dementia Friends” initiative.

It is reported as, by 2015, 1 million people becoming Dementia Friends. The £2.4 million programme is funded by the Social Fund and the Department of Health. The scheme has been launched in England and the Alzheimer’s Society is hoping to extend it to the rest of the UK soon.

A newspaper article on dementia will now have a standard format. There’ll be the story itself, a bit about dementia, and invariably a bit about Dementia Friends. But the situation is very serious indeed. It wouldn’t be tolerated if all the discussions of groceries in newspapers or online media only made references to Sainsbury’s.

This is clearly problematic for other charities such as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, who have their own longstanding friendship initiatives, but who have never publicly complained about this situation.

When the State goes into partnership with third sector organisations, the need for much more effective regulation in public-private partnerships is imperative.

This is what the OECD had to say about the issue in their document “Recommendation of the Council on Principles for Public Governance of Public-Private Partnerships May 2012″:

“Sound regulatory policy promotes the efficient functioning of regulatory agencies by ensuring that they operate under an appropriate and clear mandate, with the necessary independence from political influence and regulated subjects, that they are appropriately resourced and equipped, and that their decision-making is fully transparent and accountable,”

“Where PPPs are employed in the delivery of infrastructure facilities with natural monopoly characteristics, the role, design and organisation of regulators is important to secure value for money for the public sector and protect users and consumers. This role should be clear to all (staff, regulated entities and the community).”

“The appropriate sector regulator should consequently be consulted in the project design and subsequently monitor compliance with regulated service standards. This role is important not only in shaping the markets, but also with concrete issues such as service quality, profitability, tariffs and prices. Of particular interest in monopoly-like situations is the degree of profitability compared to the sector average using various benchmarks.”

There are good business management reasons why such entities are able to exert monopoly-like effects. Large organisations benefit from ‘economies of scales’, meaning that it is cheaper to do things in bulk. And large organisations can afford, say, to attend conferences, pay for posters, stand space, marketing pamphlets, etc.

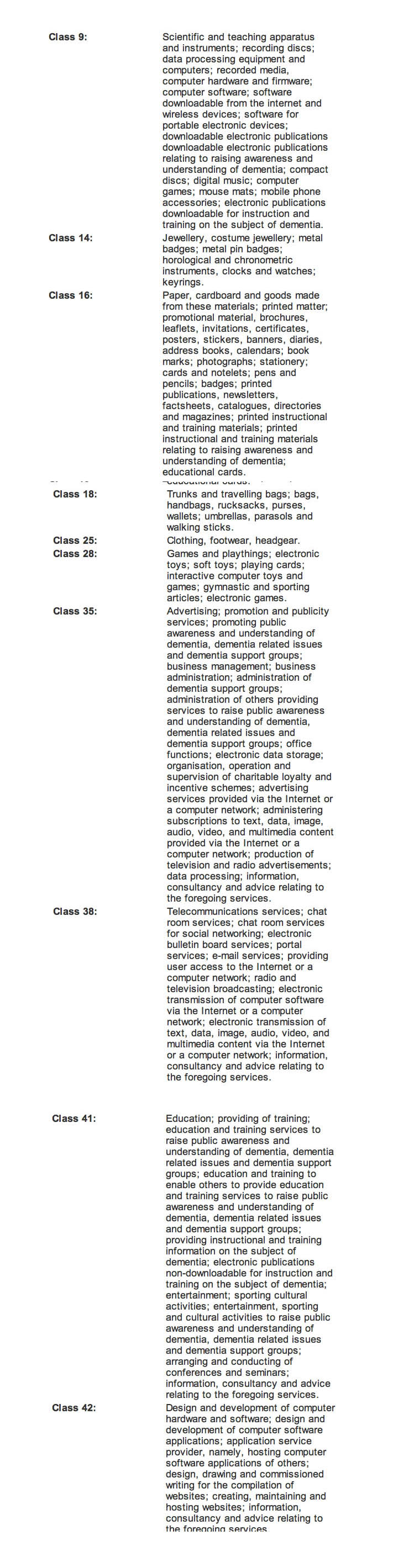

It is simply impossible for smaller organisations to compete with this. For example, large charities are able to instruct commercial/corporate law firms to protect their logos and trademarks on intellectual property registers; and are able to exert competitive advantage that way.

And this was from Public Health England last year:

“The aim is to create a fully-integrated marketing programme which will help transform how the public thinks and feels about dementia, increase social connectedness and upskill society, so that people understand how they can help. It will encourage people to join the Dementia Friends programme, launched by Alzheimer’s Society, and invite businesses and communities to become dementia-friendly organisations.”

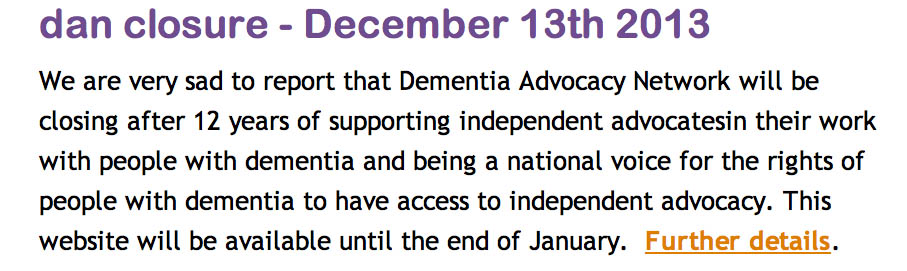

There’s been a whole plethora of cutbacks, which have thus far gone relatively unnoticed under the RADAR of the mainstream media. For example, it is reported that Essex County Council has just finalised plans to axe £200,000 funding for Mundy House, the only dementia day care centre in South Essex.

A number of people have told me in private that they cannot compete with the Alzheimer’s Society, but are increasingly having to find strategic partnerships with them otherwise they really would have no hope of competing in commissioning, even if they feel that their values and project are distinct.

The suboptimal nature of this sometimes bursts onto Twitter, where it can be difficult to have a highly managed media message. Tommy Whitelaw, well respected campaigner for carers’ voices, wished the Alzheimer’s Society to share his video, and these were some of the responses when the video wasn’t shared.

what on earth?Why won’t you RT a heartfelt film about carers/dementia, @alzheimerssoc ? Dementia doesn’t consider borders!  @tommyNtour

@tommyNtour

— #hellomynameisRachel (@StMHNurseRahs) March 31, 2014

@tommyNtour @alzheimerssoc : Are you saying that the issues highlighted in the film don’t apply to carers in England?

— joyce cavaye (@joycecavaye) March 31, 2014

For all of twelve hours I had forgotten about this major problem, until this reminded me:

“don’t bite the hand that feeds you” mantra keeping big dementia charities in the pocket of government? Not as influential as we think?

— Darren Gormley (@MrDarrenGormley) April 1, 2014

And a friend of mine on Facebook, who had been a longstanding supporter of the Alzheimer’s Society, and who himself/herself lives with dementia, complained last night that (s)he was very dillusioned about his/her views weren’t being listed to, amongst a plethora of other grievances about the current direction.

(S)he had just in fact read my survey about who were the winners and losers of the G8 Dementia survey according to about 90 of my followers on Twitter.

I think this situation is intolerable. I intend to write to the Alzheimer’s Disease International about my concerns, because we need a diversity and plurality in fundraising for all the dementias. I know that I already have the support of many who are equally concerned. All we need, I feel, is an open and transparent debate about what or who is calling the shots in English dementia policy.

And finally, this tweet has summed up my concerns. Thanks Bernadette.

@legalaware This was always the danger of ‘Big Society’ or PPP concept: some charities losing independence, some becoming the ‘chosen ones’.

— Bernadette Meaden (@BernaMeaden) April 1, 2014