Picture above of Norman McNamara (left) and me at the Queen Elizabeth II Centre yesterday.

A summary of the book and a programme for the book launch (by invite only) is here.

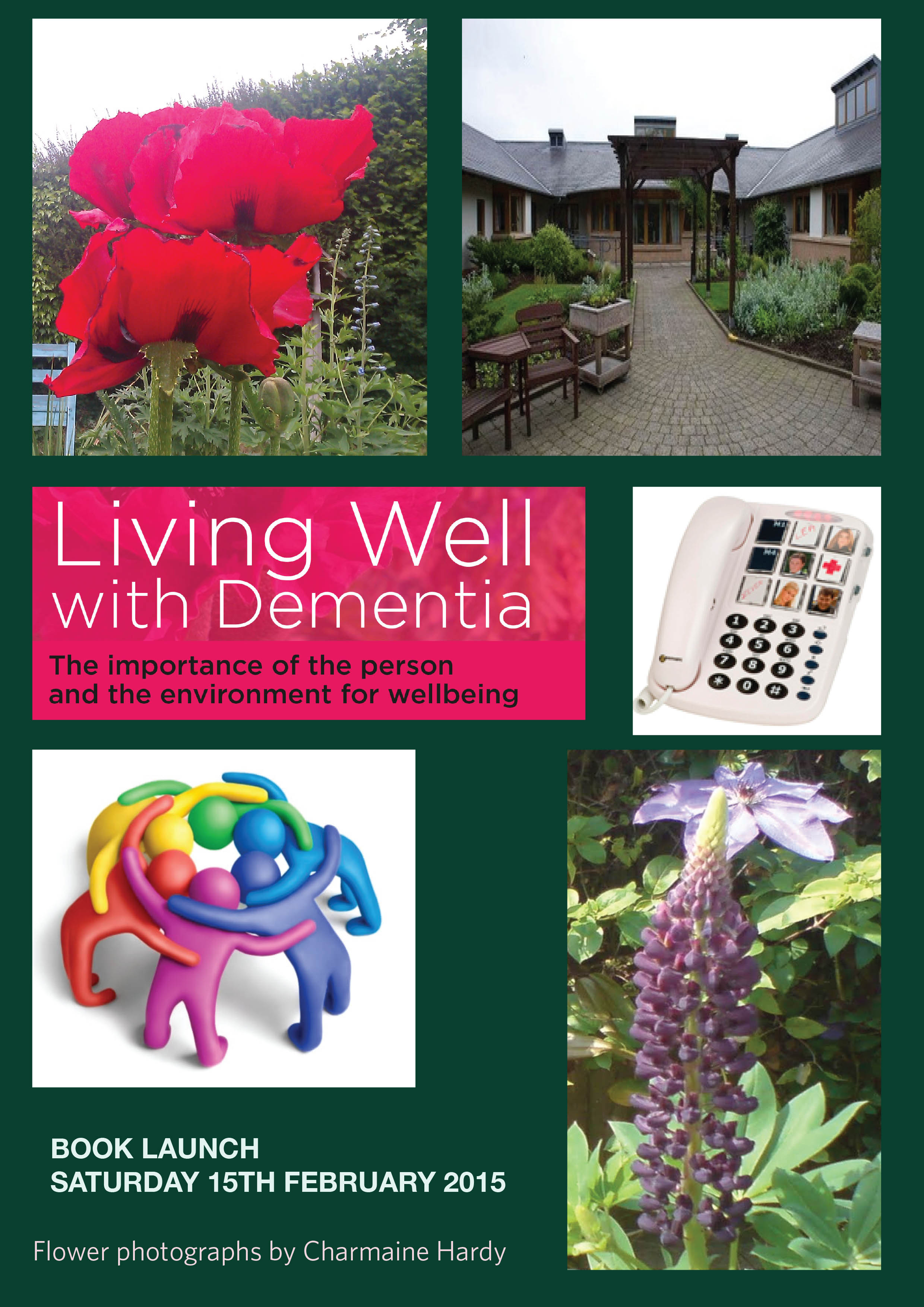

Here is the cover with Charmaine Hardy’s flower pictures. Charmaine Hardy is a key #dementiachallenger (@charbhardy).

Links to material

Amazon page

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Living-Well-Dementia-Importance-Environment/dp/1908911972

Publishers page

http://www.radcliffehealth.com/shop/living-well-dementia-importance-person-and-environment-wellbeing

Contents

Dedication • Acknowledgements • Foreword by Professor John Hodges • Foreword by Sally Ann Marciano • Foreword by Professor Facundo Manes • Introduction • What is ‘living well with dementia’? • Measuring living well with dementia • Socio-economic arguments for promoting living well with dementia • A public health perspective on living well in dementia, and the debate over screening • The relevance of the person for living well with dementia • Leisure activities and living well with dementia • Maintaining wellbeing in end-of-life care for living well with dementia • Living well with specific types of dementia: a cognitive neurology perspective • General activities which encourage wellbeing • Decision-making, capacity and advocacy in living well with dementia • Communication and living well with dementia • Home and ward design to promote living well with dementia • Assistive technology and living well with dementia • Ambient-assisted living well with dementia • The importance of built environments for living well with dementia • Dementia-friendly communities and living well with dementia • Conclusion

Introduction

There are probably close to one million people currently living in the UK with one of the hundreds of dementias, it is thought.

Plan [by prior invitation only]

Please do not attend if you have not been invited – there are strict limits for both venues.

Saturday February 15th 2014

3 pm I will give a talk on ‘Living well with dementia’ at the Arlington Centre, 220 Arlington Rd, London, Camden NW1 7HE.

I will introduce my book, and how this has become a critical plank in English dementia policy. this will be followed by tea and coffee for my guests to meet each other.

The book will be available to see (due to be published on January 27th 2014), and arrangements will be made for the book to be made available at a discounted rate from the publishers.

7 pm Dinner at Pizza Express, Southampton Row, London. WC1

(near the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Queen Square, London), 114-117 Southampton Row, London.

Background

There is actually surprisingly little awareness of what “wellbeing” and “living well” actually mean. In the absence of an understanding of the academic background to these terms, they are at risk of being used as merely marketing devices. And yet, their relevance is very real. The Care Bill is just one recent example of a statutory instrument where wellbeing has to be given priority in commissioning decisions, and be seen to do so.

Sadly, relatively uniquely, I have nothing to gain particularly by discussing these ideas. I did my own Ph.D. in dementia at Cambridge, and, also from a medical background a long time ago, I hope that I can give a balanced, accurate account of some of the policy decision-tree in dementia in England. “Living well with dementia” is, in actual fact, the name of the five-year national dementia strategy for England, which is (hopefully) about to be renewed.

A diagnosis should not be the first step to medical professionals or the rest of society in writing an individual off. My views are deeply entrenched in inclusivity, reciprocity and solidarity, and so it will not surprise you that I do not feel myself in competition with anyone. The people who are most influential to me in my view of the dementias, as an academic, are those people living with dementia. I hope many of them are living well, but it should be the aim of everyone for us all to live better. My book hopefully is a realistic look at various policy planks, including the proposed use of assistive technology, better design of the home and built environments, forming stronger communities, and promoting various lifestyle activities.

It’s an important narrative which has a huge amount of evidence about it, and my simple aim has been to take it out safely out of the worlds of academia and wonkland, and to bring it to the general public. I hope you enjoy my book!

What is “living well with dementia”?

This book is quite unusual as it is not a medical textbook, and yet I feel the book would enormously helpful and interesting for senior doctors working in this specialised area. There are common myths about ‘living well’. It’s not just about happiness. It’s not simply the absence of illness. It’s about something uniquely and personal. For any one person, it’s a complex interplay of cognitive factors (such as reasoning and memory), mood, and psychological and physiological wellbeing (such as physical and social factors). One of the earlier chapters is devoted to discussing the various definitions of ‘living well’, and how this might possibly be measured.

I believe, pretty, strongly that this is not a sterile academic debate. It’s about fundamentally what we’re like as persons, our interaction with one another, our interaction with the environment, quality of care, and properly funded health and social care services. The medications which have been developed sometimes have been marketed with rather hyperbolic claims, but for many the ‘anti-dementia’ drugs known as cholinesterase inhibitors have rather modest effects. Meanwhile, the reality is funding for community clubs encouraging people with dementia to meet up and participate in activities has been threatened, and funding for advocacy for certain persons with dementia to defend their legal rights has been withdrawn altogether.

“Dementia” is likewise not an unitary phenomenon. The term ‘dementia’ is often used synonymously with Alzheimer’s disease, which does typically present with memory problems, but there are hundreds of different types of dementia in the world, some of which do not even present with memory problems. This conflation in language has hampered a cogent narrative on how we diagnose dementia – and there is currently concern that some individuals are receiving a diagnosis of dementia rather too late – and how we ‘cure’ dementia. Knowing what type of dementia a person may live with (the cognitive neurology) can potentially allow people to be on the lookout for potential challenges that person might face – e.g. spatial navigation, which could be addressed through appropriate signage in the external environment. Knowing what type may also be particularly relevant to communication techniques, but often basic things in conversation can often be poorly done quite disappointingly.

I got through my entire undergraduate medical training at Cambridge, and indeed a neurology foundation year job at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery at Queen Square, without ever knowing about Tom Kitwood’s seminal work on “personhood” (1997). And yet this concept of persons with dementia, rather than necessarily patients, is fundamental to how I feel about this subject. I have a few friends with dementia. I learn loads off them. If one friend, for example, supports surveillance monitoring through GPS tracking, I support him or her. If it’s considered to be an unacceptable intrusion on personhood, I respect that too. But the point is, I don’t think it’s right for others to “judge” what people can’t do – it’s what persons with dementia can do which counts. I do not discuss factors involved which may contribute to delayed diagnosis across a number of jurisdictions, but I do address how English policy has attempted to identify people with dementia.

I wear a number of ‘academic hats’. One of them is, surprisingly, innovation management. You’ll see this influence in my book towards the end. I think of persons with dementia as part of the ‘network’ needed to bring about a cultural change in how healthcare views dementia, in a form of “distributed leadership”. In this network, there are many actors, not just the “usual suspects”. Adoption of innovations also looms large in my book, with two chapters devoted to assistive technologies (and the research behind them) and ‘ambient assisted living innovations’. It’s just incredible to think how much progress has been made in this area, ranging from output from the Design Council to that from massive EU-funded initiatives. Ultimately, there’s a good economic case as well for promoting living well with dementia. Nonetheless, whilst being optimistic, I have endeavoured not to produce a sanitised version of ‘living well with dementia’: I describe for example living well in end-of-life care, and particular phenomena which might be particularly relevant here.

But the problem with wearing so many hats is that you can all too easily enter a ‘silo mentality’. It’s though definitely the case the various topics do connect together. Whatever your views about the policy drive towards a ‘timely diagnosis’, a prompt and correct diagnosis can potentially lead to better care. Housing is one of the important ‘social determinants of health’, and attention to what works best in the external environment and through design features of the home can massively improve the quality of life of a person with dementia. Hospitals can be very disorientating for patients with dementia too, and this must be borne in mind when designing a ward environment – patients with dementia represent a high proportion of acute presentations in the elderly too. And adopting a community-oriented approach means that a person with dementia is a friendly and supportive environment, and this of course requires some ethical reconciliation with the themes of autonomy and independence. This has been an important converging area of policy, and goes including the person with dementia in any decision-making, reflecting key aspirations of choice and control (whatever your ideological viewpoint).

The main aim of this book is to take the discussion out of a specialist area, in such a way that we – as citizens – can all discuss the issues involved, and come to an informed opinion. I hope therefore you enjoy the book!

Key reference

Kitwood, T. (1997). Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first. Buckinghamshire: Open University Press.