The authors of this piece are Rebecca Myers and Shibley Rahman.

Rebecca Myers (RM) is an Organisational Development Practitioner/Return to Practice Community Staff Nurse).

Dr Shibley Rahman (SR) is a former junior doctor, and currently an academic physician in dementia.

We are posting this on a freely available blog and we welcome any comments you have on this topic. Whilst not specifically related to the focus of this site, this is an important blog which is helpful for people at large to reflect on.

Introduction

- “We are so sorry but …”

- “You know that patient you saw last night…”

- “There’s been a complaint and it concerns you…”

- “We’ve missed our quality/financial target this quarter…”

- “If you do/say that your position is untenable…”

These are just some of the phrases that trigger an emotional response of fear, and can affect us all whether we are a member of the public, a health professional, Board Director or the Secretary of State for Health.

How we respond to our feeling of fear can lead to a number of constructive or destructive consequences for patients, staff and the NHS as a whole.

This piece seeks to provoke thought, discussion and change using learning from neuroscience and the social sciences. It is aimed at a wide audience of patients, professionals, politicians, press and the population at large; we believe it is only by a shared/broader understanding of responses to fear, and individual and collective responsibility for our responses and their potential consequences, will we be able to create a possibility of talking openly and honestly about issues that affect the performance and future of the National Health Service.

This in turn can encourage a dialogue with a range of people who might be touched by the issues. We hope that with exploration of the ‘science’ behind fear and responses to it we might head towards a more inclusive and generative set of solutions for the challenges in the NHS for the benefit of patients, staff and the public.

Personal perspectives

Our personal responses are worth some scrutiny to illustrate the theory and the science.

We are, like everyone else, acutely aware of feeling fearful. If you return to clinical work after a protracted period of time out (as indeed one of the authors, RM, has done), you can become engaged into a ‘conscious incompetent/competent’ state. This is where you have to think so much harder to achieve the same result. It also means that, depending on the precise moment-by-moment situation, you can be prompted into a whole range of emotions from curiosity to frustration to enthusiasm and outright fear. Initially described as “Four Stages for Learning Any New Skill”, an influential theory developed at the Gordon Training International by its employee Noel Burch in the 1970s (Adams, date uncertain) offers a framework for understanding and then managing fear in learning situations.

An explanation of fear and blame

It is important in exploring fear not to be unhelpfully reductionist. But it has long been recognised that fear can be manifest as an outright ‘flight or fight’ response as per Walter Cannon (1932); it has its biological basis as a primitive survival mechanism alerting us to potential threat and enabling us to respond in a way that keeps us safe.

Damasio (1994) introduced the “somatic marker hypothesis” which suggests structures in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex provide the substrate for learning an association between certain classes of complex situation on the one hand, and the type of bio-regulatory state (including emotional state) usually associated with that class of situation in past individual experience.

The establishment of a somatosensory pattern appropriate to the situation via the ‘body loop’ or the ‘as-if body loop’ both overtly or covertly is co-displayed with factual evocations pertinent to the situation and qualifies those factual evocations. This constrains the process of reasoning over multiple options and future outcomes and ‘shortcuts’ to a judgment of the scenario as either good or bad.

When this is overt the somatic state operates as an alarm signal. When covert it operates a biasing signal, which in turn influences cognitive processing.

This suggests that interpretations of situations and learned responses to these (including those laid down in early childhood) guide our reactions to situations we may consciously or unconsciously perceive as fearful.

That the brain processes the precise emotion of fear in a distinct way is indeed supported in cognitive neurology evidence. It has been known for some time that a part of the brain, called the amygdala (so called as it is shaped like an almond), is somehow involved from rare experiments of nature. But the neural network involved might be more extensive than first hypothesised (Khalsa et al., 2016).

Why the response to fear is personal

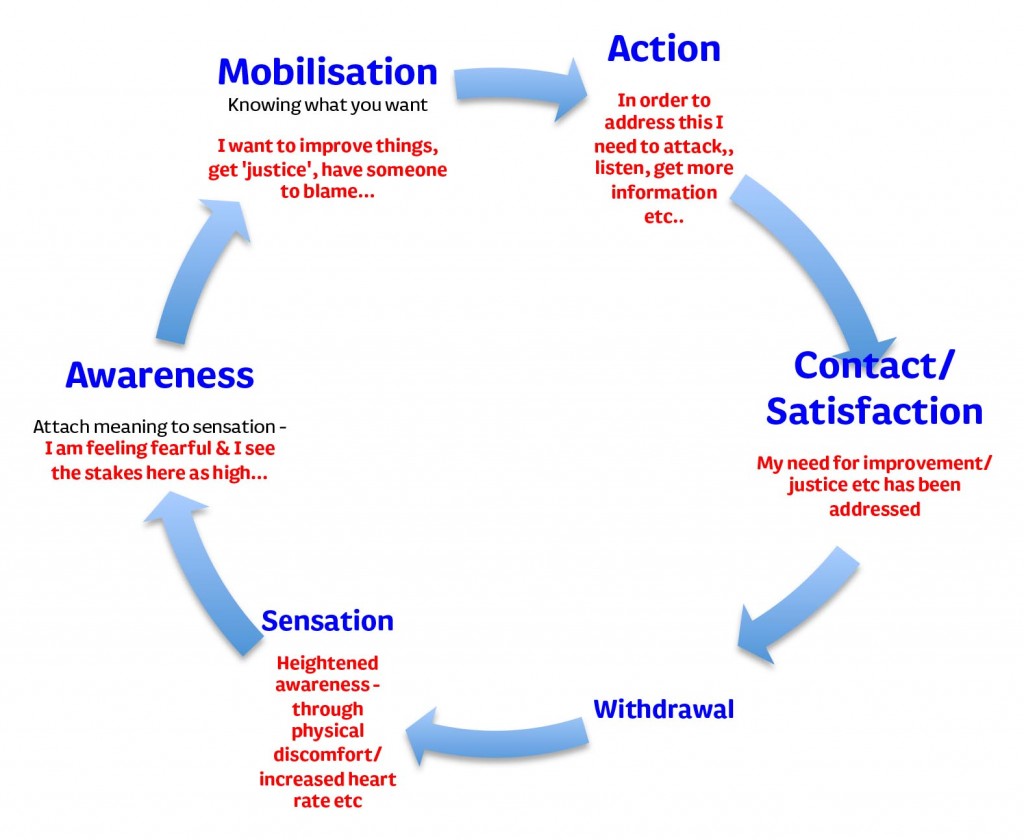

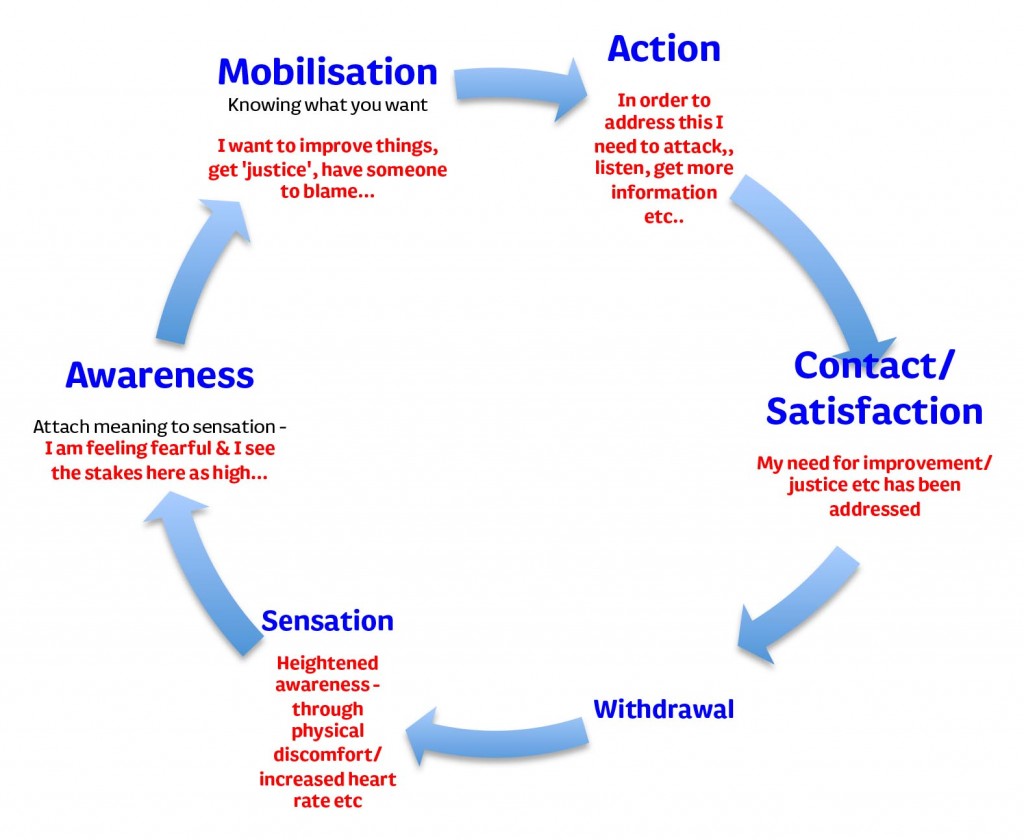

Once the emotion/sensation of fear has arisen we have various conscious and unconscious response options. If we take a Gestalt perspective, we would say we ‘need’ to respond in a way that addresses the original sensation or else we remain in a heightened state of awareness. This would prevent us from ‘moving on’ from the situation we had encountered (this is shown in an adaptation of the ‘experience cycle’ presented by Zinker, 1977).

How the sensation leads to different emotions, is influenced by the context in which we see ourselves, and the subsequent meaning we attach to them. (See, for example, Gergen’s work on social constructionism https://vimeo.com/15676699.) Using the example of facing a situation back in practice to illustrate, will my actions help or harm the patient, and to what degree? Is there someone supportive nearby to guide and assist me if I get stuck? If I make a mistake what will happen to me?

Whilst we might have a biological predisposition to reacting in a certain way as a learned response, it is possible that our individual childhoods might contribute to these learned responses and adult psychopathology (Rich, 2006). Thus, in my moment of fear, if I define the situation as one of potential failure do I choose to say “I can’t do this” and risk a reaction from the patient of lack of future trust, or my mentor of seeing me as having less ability or potential which in turn affects my ability to practice? Our ability to formulate a constructive response to this in the moment may be hampered by a tendency to fragment and simplify the problems, rather than to see the reality of the situation as a whole. This is demonstrated by the framing of the narrative by the physicist, David Bohm who describes the importance and need for ‘wholeness’ when looking at and responding to situations.

The neurocognitive explanation might appear deceptively straightforward, but in reality involves a complex process map including task selection and decision-making in the prefrontal cortex and related structures (Gleichgerrcht et al., 2010).

When the emphasis changes from the individual to broader organisational learning

If we extrapolate the response of an individual to a fear response to the group or organisational level we can observe situations where in the desire for learning or accountability there is a desire to find someone to blame. There is a concern if no-one is held to account, such as in Mid Staffs or Southern Cross, that any misfeasance goes undetected and so, effectively, unpunished? This can then lead to a sense of things being unresolved or lessons not learnt, which can leave people unable to withdraw or obtain closure.

Again taking the personal to illustrate, becoming a ‘marked man’ by a regulator can also put you on edge, even if you have had your problem mutually resolved between you and your regulator. Somewhat paradoxically for the regulator, if following this experience you are so petrified of making a mistake, you put yourself at greater risk of making a mistake. The aspiration that a clinician (or anyone else) never makes a mistake is of course ideal, but this flies in the face of the reality of life (clinical or otherwise). It’s what is well known by people who’ve faced addictions as the “don’t think of elephants” phenomenon – your first response to not thinking of elephants is to think of an elephant.

The experience of one of us (SR, having been through the entire cycle of disciplinary procedures by a clinical regulator when very sick, and then restored when well), albeit individual, outlines the tension between the rhetoric of organisational learning and ‘learning from failures’.

This experience (for SR) was an utterly demoralising, destructive, experience, but from which a recovery revealed itself, both in mental health and professionally. This personal experience coincided with a period where that regulator had a problem of a number of alleged suicides due to the investigative process (Davies, 2013). It is still not widely understood how the regulation of an individual and the contributory factors for the case are related to the regulation of the system and its working environment and how by focusing on one you might address the other.

What is important to think about is that the essential biological response to fear plays out moment-to-moment wherever we ‘sit’ in the context of the NHS and the consequences that arise from our responses impact not just ourselves but also those around us and, in some cases, the whole system. This is seen not only in high profile clinical/care cases such as the Bristol Inquiry, Mid Staffordshire, Baby Peter and Winterbourne to name just a few but also in the responses to the Health and Social Care Act, funding decisions in the NHS and social services, and approaches to regulation.

This issue applies to everyone

We argue that this issue is of relevance to us all. An inability for any of us to ‘manage our fear’ in order to deal with the issues involved in a reasoned way risks preventing us from moving forward: ‘Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.’ (Albert Einstein)

It is worth thinking about whether the fear around the NHS serves any evolutionary advantage, which offers an opportunity for something better. Does it make us better clinicians in our normal clinical life? Is it supposed to tune us in sharply in what is deemed unacceptable by the public at large or raise our awareness around the future of a much loved institution? Or is it rather that the moral panic that can ensue is not the best climate calmly to formulate clinical decisions or policy?

For all involved, from ministers to families, events referred to above, understandably evoke a range of emotions of which fear will play a significant part. We ask, and say to, ourselves: “I could have done more”; “How did I allow my loved one to be treated like that?”; “Why didn’t I speak out?”; “Will I lose my job/reputation/election?”. We are not commenting on the hierarchy of these questions or making judgement here on what is or isn’t appropriate but highlighting the commonality around how our emotions are evoked which leads to a response which in turn leads to a consequence. Being able to be thoughtful about the potential consequences of our own reactions in these moments (or, in the case of the type of examples above, significant periods of time) whilst difficult can be extremely valuable.

As Manoj Pawar (2007) notes:

“As a result of the fear-based emotions linked to blame, people tend to shift their energies from understanding and learning processes for the interest of the group toward self-preservation, attacking and defending their individual interests.”

If I respond with the ‘fight’ response by attacking the representation/manifestation of my fear will I push others to defend and fight back or run away (flight)? Will that then help with the situation I, or the system, am facing?

But a slower cognitive process can later modulate what is conceivably an appropriate evolutionary response. It is well known that slower clunky parts of the brain involved in planning act as a check on the faster response (for a discussion of the wider context of this, please see Haidt (2011) and Kahnemann (2012)).

The authors of this piece want to be very clear they are not suggesting not raising issues or questioning mistakes or policy decisions, but highlighting the importance of doing so in a manner that enables people to think and reflect not overwhelm or evoke defensiveness and denial. Perhaps adopting what Edgar Schein (2013) describes as a “humble inquiry”, which advocates asking questions to understand what has happened and why, refraining from judgement and keeping an open mind.

This can guard against the well known psychological phenomena of ‘confirmation bias’.

“When we think that a particular course of action is correct, our tendency is to interpret any available information as supporting that thinking. This is known as confirmation bias.” (Beshears and Gino, 2015).

The world of social media has opened up the dialogue and given voice to those who often weren’t heard. It is changing the relationship between different groups. The social care blogger @ermintrude2 recently analysed this phenomenon of ‘flattening hierarchies’, and what might actually be behind this meme (@ermintrude, 2015).

Both positive and negative consequences?

With this brings both positive and negative consequences and there’s a fine line between possible outcomes.

Positive experiences undoubtedly occur around sharing experiences, raising issues challenging assumptions, enabling dialogue, building networks and sense of community. “John’s Campaign” http://johnscampaign.org.uk is one example of a brilliant organic campaign for carers to accompany patients diagnosed with dementia into hospital, which has become a new NHS quality target (known as a CQUIN).

But there is a flip side: trolling, public abuse, combative debate, personal attack and groupthink; all can be fear inducing and again provoke fight – flight responses. At worst, individuals, previously well, can go into a spiral of decline of profound depression, and, if the narrative provides no sense of hope for improvement, we can see a state of ‘learned helplessness’ develop around people’s ability to change the situation (Vollmayr and Gass, 2013).

No one is immune from this – from junior doctors who in statutory law do not have whistleblowing protection (Cooper, 2016), to relatives trying to get answers following a mistake or unexpected death, to senior managers having their personal lives plastered over the front page of the newspapers – codifying just how vulnerable we all are.

People talk about a ‘blame free’ culture or a ‘just’ culture within the NHS as if the culture of the NHS is: (a) homogenous and b) determined purely by those within the ‘system’. But we argue that this fails to recognise the wider ecosystem and what Ralph Stacey (2001) refers to as the complex responsive processes that are set in motion when any of us do something (https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=RTAV7-FZLRs). This can make the discussions about who is to held to account, and how, complex and controversial.

A need to be honest about what we mean about ‘shared’ leadership

We would suggest that all of us contribute to this culture either directly or indirectly, and to ignore this is essentially a “wilful blindness” to the harm that is done when patients, the population at large, staff (be it clinical, administrative, social services or managerial) and politicians are not listened to in a blame culture. This will inhibit our ability to learn from experiences, good or bad (Heffernan, 2011). And wilful blindness can occur anywhere in healthcare ecosystems.

Peter Senge (2006) has written extensively on the learning disciplines – we individually and collectively need to foster to create a ‘learning organisation’ and both Sir Robert Francis and, more recently, Don Berwick referred to this as essential for the NHS to not just survive, but also thrive in the current climate of quality and financial challenges (National Advisory Group on the Safety of Patients in England, 2013).

So if we always do what we’ve always done…

Arnold Beisser’s (1970) Paradoxical Theory of Change argues, “change occurs when one becomes what he is, not when he tries to become what he is not”. So next time something happens which evokes a sense of fear and anxiety whoever you are or wherever you sit within the ‘system’, remember the chain of complex responsive processes you may set in motion and ask yourself, “am I creating an environment of curiosity, learning and change?”

Or, are you in fact perpetuating a culture of fear and blame, that takes us further from where we want, and more importantly, we believe, need to be?

London, 1 April 2016.

References

@ermintrude2 (2015) Flattened hierarchies (blogpost dated Nov 8, 2015), https://medium.com/@ermintrude2/flattened-hierarchies-ee54e9ba2cfc#.bcin2dknp.

Adams, L. “Learning a New Skill is Easier Said than Done”.Gordon Training International. http://www.gordontraining.com/free-workplace-articles/learning-a-new-skill-is-easier-said-than-done/ (page accessed 11 March 2016).

Beisser, A. (1970) Paradoxical Theory of Change, Gestalt Journal Press http://www.gestalt.org/arnie.htm

Bergias, S. (2013) Truth-Resistant People, Leadership Excellence, March 2013, pp.11.

Beshears, J, Gino, F. (2015) Leaders as Decision Architects, May, https://hbr.org/2015/05/leaders-as-decision-architects.

Bohm, D. (1980) Wholeness and the Implicate Order, Routledge.

Cannon, W. (1932) Wisdom of the Body. United States: W.W. Norton & Company.

Cooper, B. (2016) How the government is leaving whistleblowing doctors to twist in the wind, New Statesman (25 February 2016), http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/health/2016/02/how-government-leaving-whistleblowing-doctors-twist-wind

Damasio AR. (1994) Descartes’ error and the future of human life. Sci Am. Oct;271(4):144.

Davies, M. (2013) GMC launches internal review of suicides among doctors facing fitness-to-practise investigations, Pulse Today, http://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/your-practice/regulation/gmc-launches-internal-review-of-suicides-among-doctors-facing-fitness-to-practise-investigations/20004473.fullarticle (page accessed 11 March 2016).

Gleichgerrcht E, Ibáñez A, Roca M, Torralva T, Manes F. (2010) Decision-making cognition in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurol. Nov;6(11):611-23.

Haidt J. (2001) The emotional dog and its rational tail: a social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychol Rev. Oct;108(4):814-34.

Heffernan, M. (2011) Willful Blindness. Walker & Company, 2011.

Kahnemann, D. (2012) Thinking fast and slow, London: Penguin Books.

Khalsa, SS, Feinstein,JS, Li, W, Feusner, JD, Adolphs, R, Hurlemann, R. (2016) Panic Anxiety in Humans with Bilateral Amygdala Lesions: Pharmacological Induction via Cardiorespiratory Interoceptive Pathways, The Journal of Neuroscience, 23 March, 36(12): 3559-3566.

Mendick, R, Donnelly, L, Kirk, A. Medical blunders cost NHS billions, Telegraph, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/health/news/11733719/Medical-blunders-cost-NHS-billions.html 11 July 2015 (page accessed 11 March 2016).

National Advisory Group on the Safety of Patients in England (2013) A promise to learn – a commitment to act: Improving the Safety of Patients in England, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/226703/Berwick_Report.pdf.

Nenadic I, Güllmar D, Dietzek M, Langbein K, Steinke J, Gaser C. (2015) Brain structure in narcissistic personality disorder: a VBM and DTI pilot study. Psychiatry Res. Feb 28;231(2):184-6.

Pawer, M. (2007) Creating & Sustaining a Blame-Free Culture: A Foundation for Process Improvement, The Physician Executive, July/August, pp.12-13.

Rich P. (2006) From theory to practice: the application of attachment theory to assessment and treatment in forensic mental health services. Crim Behav Meant Health, 16(4):211-6.

Schein, E.H (2013) Humble Inquiry: The Gentle Art of Asking Instead of Telling. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Senge, P.M. (2006) The Fifth Discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization: Second edition, London: Random House.

Stacey, R (2001) Complex Responsive Processes in Organizations: Learning and Knowledge Creation (Complexity and Emergence in Organisations), London: Routledge.

Vollmayr B, Gass P. (2013) Learned helplessness: unique features and translational value of a cognitive depression model. Cell Tissue Res. Oct;354(1):171-8. doi: 10.1007/s00441-013-1654-2. Epub 2013 Jun 13.

Zinker, Joseph, (1977) Creative Process in Gestalt Therapy. New York: Brunner/Mazel Publishers.