I have written previously on my gross dislike of military metaphors in discussing dementia, but there is one particular description which was used fleetingly by Marc Wortmann’s presentation this year in ADI 2015 Western Australia that I think is helpful.

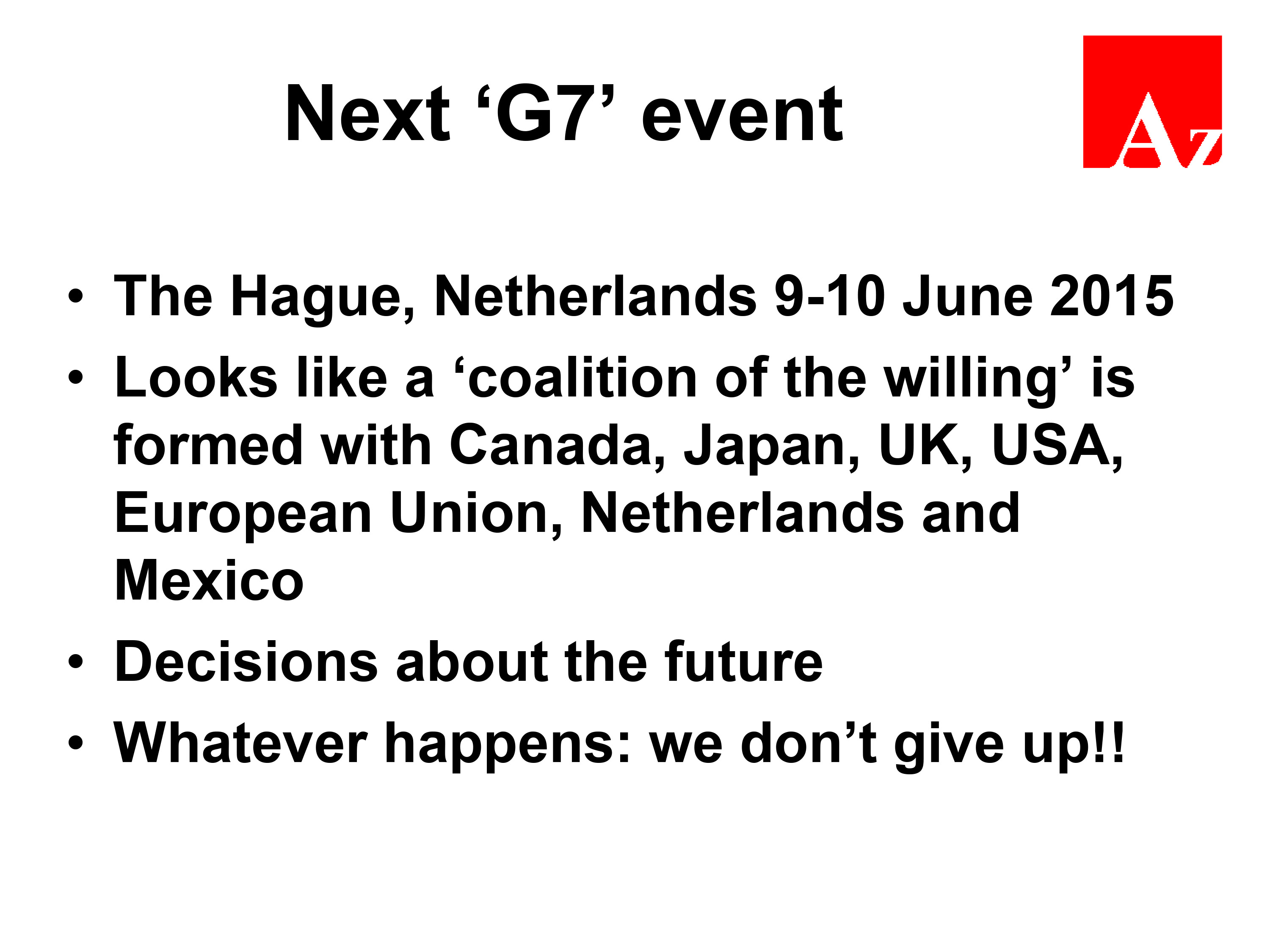

This is the reference to the ‘coalition of the willing’. It happens to have been most recently in reference “to a group of allied countries in a military intervention, especially the United States and its allies in the Iraq War.”

Alan Milburn was recently musing at the Centre for Social Justice about how Labour predictably lost the General Election in 2015. There, Milburn stressed the need for strong leadership and, above all, the need for a strong vision. Although Milburn warned against a “35% strategy”, micromanaging its ‘offer’ to various parts of the electorate who’d disappeared (such as in Scotland or to UKIP), Milburn suggested a “100% strategy” appealing with boldness.

Similarly, I feel the English dementia policy (or rather the implementation of it) has tragically lost its way. It’s written in a chain-letter way trying to micro-manage its offer to various people such as NHS England or Big Pharma. It’s a pity these policy documents never appear to mention certain stakeholders much, however.

Whilst one might not agree with the content of Milburn’s politics, I feel these points taken cumulatively need to be applied to developing the new English dementia strategy.

I still believe very strongly that vision for dementia policy must be whole person care. Care currently is broken with haphazard communication between health and social care bodies, and people with dementia and carers not being listened to nearly sufficiently adequately. Parity of esteem’s impossible wthout adequate resources, and health being ring fenced is a Pyrhhic victory with social care funding on its knees. Physical health affects mental health, and vice versa. Dementia care needs to be strongly assets and strengths based, with a real attempt to avoid crises or avoidance of ‘fixing’ things at the last minute.

Enshrined in the code of conduct of social workers is the need to preserve dignity, fight against inequality, uphold social justice, wage war on discrimination, and uphold human rights. The social work profession are in an unique position to be professionally involved with the dealings of the Mental Capacity Act and Mental Health Act. The new statutory requirements of the Care Act has seen an obligation to promote wellbeing, an option for personal budgets, an emphasis on advocacy, and prominence of safeguarding. Unifying all of us is our need to engage with risk to live better.

With the ‘new models of care’ in the NHS Five Year Forward View (and beyond, such as from ongoing work at the King’s Fund), it is clear that various new models of care, like PACS or the multispecialty commmunity providers, are ideally suited for more effective service provision of dementia suited to the needs of people living with dementia. That primary care is not just GPs, and it should be much easier to get in and out of your own home, residential home or acute hospital as or when you need to should be top policy priorities now.

It’s clear to me specialist nurses must have a seat at the table. The need for this is two pronged. They are not only needed for the nursing needs of a person living with dementia, as or when they might arise at any stage after diagnosis. But there is also an overwhelming need to look after carers in their needs, including the enormous body of more than a million unpaid family members. Whilst many policy devices have seen carers getting more prominence in dementia policy, it’s clear there’s more to be done, such as enshrining the rights of carers in the NHS constitution, including companion rights for acute hospital admissions.

All of this depends on the person being diagnosed correctly with a dementia. But it’s not good enough that a person is given news of a possible dementia. We amongst all of us need to define better what ‘post diagnostic support’, as it’s currently far from clear what this is and who should be doing it. It’s clear that there are some components which ‘must be there’, such as end of life care, but we do need to have the debate about the ‘good death’, and who will help with advance care planning, why and where.

We need a frank discussion about resources. It’s simply not good enough to receive ‘a diagnosis of dementia’. We ideally need to know what type of dementia a person is living with. Might a person be living with a type of temporal lobe frontotemporal dementia where speech and language intervention might be helpful, or might a person be living with early Alzheimer’s disease where memory aid assistive technologies are now internationally available? Might a person living with lewy Body dementia be best advised by a clinical medical doctor to avoid certain medications? The narrative now rightly has swung towards reablement and rehabilitation, and acknowledging that equality and human rights based approaches do exist for people living with dementia.

Furthermore, with people in the public internationally wanting to get hold of and use smartphone and watch ‘apps’ for themselves, such as ‘Fitbit’, might there be a case for promoting greater voluntary self care of health by people with dementia themselves? The ‘HONDA’ phenomenon is often talked about in reference to someone with a number of risk factors for morbidity: such as hypertensive, obese, non-compliant, diabetic, asthma. It happens that many of the risk factors are those for vascular risk factors (along with smoking and high cholesterol), which remains a prevalent dementia for both younger and older age groups.

But it’s also true that it’s about 50/50, taking the population at large, whether dementia is caused by modifiable environmental risk factors. Sure, certain dementias run very strongly in families, but very many don’t. We need also to be able to up our game on the ‘non communicable disease’ aspect of policy, and this is indeed where social workers, along with allied health professionals, could help with preventive aspects of wellbeing and illness; and especially helping people to stay in employment, when of course they want to.

Above all, I strongly feel that people living better with dementia must lead on policy. This is not in a narrow ‘patient centric’ way in terms of their views of possible medications. We do know that despite the hyperbole of a potential cure for 2025, there have been no breakthroughs yet currently being widely utilised. The current state of play from NICE is that there are no medications which slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease or affect the symptoms for more than a short time window. If anything, I’d like to see persons living with dementia to have their voices heard loud and clear on the things that they consider would help them live better, such as music iPod social prescribing. There simply can’t be one representative for 47 million people living with dementia in the world, but stakeholder bodies such as the Dementia Alliance International (and national correlates) must now be given national policy teeth.

We’re used to seeing the ‘same old’ contributors in designing policy – but here’s a thought, the new national policy should actively promote the views of those people currently living with dementia. Co-production in service provision and research is currently a big deal, and this should definitely extend to our new ‘long term plan’ for dementia. There’s undoubtedly considerable risk and uncertainty in the strategy analysis and implementation of the English dementia strategy. We’re all aware of bodies shutting down all the time ‘due to financial concerns’, all as part of the “cut back State”, but it’s hard to escape that even ‘dementia friendly communities’, vital in promoting independent living, are dependent on robust infrastructure such as housing and transport. We need to know what the views of people living better with dementia are. Communication and leadership are key.